|

RIPSTER REVIVALS #11

An occasional column which revolves mainly around crime fiction and thrillers which have been forgotten by readers, abandoned by publishers, discarded by libraries and mislaid (or simply missed) by me.

|

Season’s Greetings

Being the time of the year that it is, it is incumbent upon me to wish everyone a ‘Merry Christmas’ at least to readers in countries where that is still allowed. I am personally full of seasonal jollity thanks to the first Christmas card I received this month from a distinguished member of the Sherlock Holmes Society.

Regrets? Maybe a few.

With great age comes the inclination to look back over a diverse career of writing, editing and analysing crime and thriller fiction and to ponder the possibility that, implausible as it may seem, one’s earlier judgements may have been injudicious or superficial. I am sure that the Greeks had a word for this feeling, they usually did and were he still with us, it would be only a phone call away on the tip of the tongue of my dear friend Colin Dexter.

Since the publication my award-winning (I am contractually obliged to say that) ‘reader’s history’ of British thrillers, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang in 2017, it has preyed on my mind that I might have short-changed two fictional characters from the boom in spy fiction of the 1960s.

One of them, inevitably labelled as ‘the female James Bond’ was Modesty Blaise, as created in book and comic-strip form by Peter O’Donnell and the subject of an amazingly bad Joseph Losey film in 1966. Having been verbally assaulted by no fewer than two die-hard fans of the Modesty Blaise books (I have yet to meet anyone who liked the film apart from Quentin Tarantino) of which there were about a dozen novels or short-story collections between 1965 and 1996, Ms Blaise is firmly on my radar for a possible re-evaluation in the future.

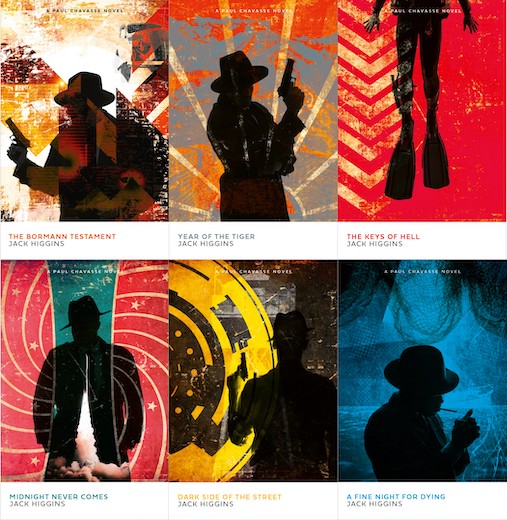

Meanwhile, news that HarperCollins are to re-issue a short-lived series from the Sixties next year has prompted me to look again at the rather perfunctory treatment I originally gave to the career of fictional secret agent Paul Chavasse.

Between 1962 and 1969, Chavasse was to appear in six thrillers, which seems enough to have kept most writers busy and probably satisfied, but not Jack Higgins (Harry Patterson) who, under various names, produced a trilogy of crime thrillers starring policeman Nick Miller and thirteen (yes, 13) stand-alone novels in that same period.

The first Chavasse adventure, The Testament of Caspar Schultz (aka The Bormann Testament) originally appeared under the name Martin Fallon – a name which, confusingly, was used for a character in two other books by Higgins – in 1962. It was a significant year for British thrillers, spies and secret agents, with the release of the first Bond film Dr No and debut novels from Len Deighton, Alan Williams and Dick Francis.

It was, in fact, Harry Patterson’s fourth novel, though his first writing as Martin Fallon and features a character called Steiner, clearly a favourite name with the author as he was to recycle it in at least two future novels. But the hero is Paul Chavasse, a character attempting to claim a place in the growing army of fictional British secret agents destined to save the world, if not the evaporating British Empire in the spy-boom of the 1960s.

Chavasse, his English mother and French father giving him dual nationality and probably explaining his insistence on drinking champagne at every suitable opportunity, is not a James Bond clone, though there are similarities. He works for ‘The Bureau’ an off-shoot of the secret service (the Double-O Section?); his boss is known as ‘The Chief’ (‘M’?); the Bureau’s cover is the office of ‘Brown and Co., Importers and Exports’ (Universal Exports?); and it is run by Jean Fraser, a secretary with whom Chavasse is prone to flirt (Moneypenny?). But Chavasse has no military rank or back story, indeed he is an academic being an exceptional (please don’t say ‘cunning’) linguist and university lecturer (Cambridge of course) who simply cannot resist the adrenalin-rush of dangerous spy work. Fortunately he has Bond’s resilience when it comes to being drugged, beaten up and tortured, the same familiarity with weaponry and similar appetites when it comes to alcohol and cigarettes; in fact there isn’t a chapter when he doesn’t light up. Chavasse also enjoys Bond’s magnetic, often fatal, attraction for women but here’s the difference: with Paul Chavasse, the sex always arrives with genuine romance, which of course leaves him emotionally vulnerable.

The Testament of Caspar Schultz (aka The Bormann Testament) involves tracking down the memoirs of a Nazi bigwig who avoided a war crimes trial, which have been offered for publication in West Germany. British intelligence is interested, so too is Mossad, but the German police, infiltrated by ex- and neo- Nazis, are not to be trusted. Much of the action takes place around Hamburg, which Patterson-Higgins probably knew from his National Service days.

For his second mission, The Year of the Tiger (1963), Chavasse gets a change of scenery – and enemy – when he is sent to Tibet and comes up against the sadistic Colonel Li of the invading Chinese army.

Although this isn’t Chavasse’s first visit to the roof of the world as, it is revealed, he helped the Dalai Lama escape to India in 1959. His new mission involves the exfiltration of a genius mathematician who has devoted his life to being a doctor for local Tibetans, but may have stumbled (theoretically) on a method of space travel not unlike what became popularly known as ‘warp drive’.

There is much derring-do, physical hardships, gunfights, three-weeks of torture and a deeply romantic encounter all set against the icy mountainous background and isolated Tibetan monasteries, and it is rather surprising that the book went quickly out-of-print with a paperback following only years later after the eagle had landed. Year of the Tiger certainly caught the paranoia of the space race between the USA and the USSR and would have satisfied the public demand for tales of high adventure in the Himalayas, Berkeley Mather’s The Pass Beyond Kashmir and Lionel Davidson’s The Rose of Tibet had both been recent bestsellers.

Chavasse’s next missions (1965-1969) saw him scuba-diving off the coast of Albania, preventing the Russians from getting plans of the latest British missile systems, investigating a series of Russian-inspired prison breaks and even tackling people-smuggling across the Channel ( a problem, it seems, when Nigel Farage was only four!)

Towards the end of the series, Paul Chavasse was acting less as a spy and more as an undercover armed policeman and it is clear from the rest of his output at the time that Patterson-Higgins (et al) was developing new interests in both style and plotting. There again, few of the fictional ‘secret agents’ of the 1960s did any actual espionage: they were action heroes who were called in to sort out trouble. Paul Chavasse was no Bond or Quiller or Dr Jason Love or Charles Hood or John Craig, or even Michael (never ‘Mick’) Jagger – and I’m not making that last one up.

When the books were reissued in the 1990s, Jack Higgins wrote pieces to top and tail the stories in a contemporary time frame, with a retired Paul Chavasse (now Sir Paul) looking back on his career, which had seen him rise to become Chief of ‘The Bureau’. In one of them, Chavasse meets with a Mafia boss without a trace of irony in the latter’s apartment in Trump Tower in New York.

Overall, Chavasse was a decent enough hero, not afraid of the rough stuff but not invincible. He was also possibly the most openly romantic action hero of the period, but Higgins was a good story-teller and more than able to throw a shocking plot-twist into the mix, so that just when you thought Chavasse was perhaps too decent a character, he shows the cold utter ruthlessness which has helped him survive whilst playing the most dangerous game.

All six Paul Chavasse thrillers will be re-published next year by HarperCollins in new livery designed by Toby James. The first in the series reverts to Jack Higgins’ original title, The Bormann Testament.

Spy-fi; a forgotten master.

I simply do not understand why my old chum Reg Gadney (1941-2018) never seems to feature on lists of notable writers of spy fiction, even ‘bespoke’ lists by so-called experts or critics and not just those irritating ‘best of’ clickbait lists on the internet.

Reg was an accomplished novelist and television scriptwriter and many of his books feature spies – sometimes former ones, often reluctant ones – and the double-crossing world of espionage from his first, Drawn Blanc, in 1970. I had the pleasure of bring his first two novels back into print as Top Notch Thrillers, but have recently taken to reading and re-reading books from his later output.

Nightshade (1987) follows the trials and tribulations of an up-and-coming MI6 officer who, whilst having an affair with his boss’ wife, has to deal with the fall-out from a failed operation in Poland and, just to add to his to-do list, discover whether a previous generation of SIS agents (his father included) knew in advance that the Japanese were about to attack Pearl Harbour in 1941, but didn’t warn their American allies. Strange Police (2000) covers a topic still making the news: the fate of the Elgin Marbles and the plot by the shadowy ‘Secret Police’ organisation to return them to Greece. There is an outrageous plan to rob the British Museum (perhaps with the connivance of MI6) which is worthy of a Bond film, as is the main villain, who has a metal claw for a hand.

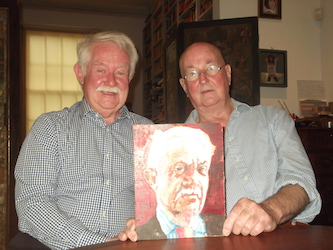

Both books are splendid reads and I had forgotten how well Reg Gadney could write. I knew he could paint, and was an accomplished portraitist, because back in 2015 he offered to paint me.

Invited to his London town house for a ‘sitting’ I was shown into Reg’s studio, passing a line of drying paintings. Pointing to one portrait, Reg asked me if I knew who it was and I had to say that I did not. ‘Good,’ said Reg, ‘or I might have had to kill you. That’s the Head of MI6.’

How did I miss this?

Having been a great fan of the work of American journalist and thriller writer Dan Fesperman since he burst on to the British scene in 1999, it was a shock to realise that I had somehow completely missed his excellent 2004 novel The Warlord’s Son. Fortunately I discovered a first edition in the second-hand section of Richard Reynolds’ crime fiction emporium in Cambridge, priced, very reasonably, at £12.99 – the exact cover price it was first published at twenty years ago.

I don’t know if Dan Fesperman, as a foreign correspondent, ever made the dangerous journey describe in the book from Pakistan through the ‘Tribal Lands’ and into Afghanistan, but this tale convinced me never to take such a trip.

It is an excellent novel featuring a doomed, over-the-hill journalist after one last scoop and the pervading threat from warlords, the untrustworthy Pakistani intelligence service and the equally untrustworthy CIA.

Two things stood out for me. Firstly, when a young woman plans to travel into the Tribal Lands in search of her boyfriend, she is warned that she is not just travelling a certain number of miles, but ‘going back 500 years in time’. And then there is a chilling moment (remember the date of 2004) where the travellers spot a mysterious ‘group of Arabs’ obviously keen to remain unnoticed on the border with Afghanistan.

From the To-Be-Read pile

I cannot remember how or when I acquired a near-pristine 1967 Pan paperback of The Missing Man by Hilary Waugh. I knew little of Hilary Waugh (1920-2008) other than he was a highly-regarded author of more than forty crime novels and a Grand Master of the Mystery Writers of America. He was best known for Last Seen Wearing published in 1952, a title Colin Dexter was also to use for an Inspector Morse story, which is widely recognised as one of the first ‘police procedurals’.

The Missing Man, first published here by Victor Gollancz in 1964 (the yellow dust jacket being an instant sign of quality crime writing), is the story of a small town police force dealing with a dead female on the local beach. With no obvious means of identification, the first problem is finding out who she was, where she came from and then the missing man who strangled her. Fairly straight forward you might think, but try doing it without computers, the internet or DNA analysis.

It's a lot of leg-work for the ensemble cast of cops, taking statements (some very unreliable), making phone calls, checking hotel records and passenger lists by hand and eye and liaising with other cops in other states. It’s a slow process, a real slog, but these cops are dedicated and throughout the trail of dead-ends and false leads Hilary Waugh maintains his readers’ interest in the progress of the investigation until the police get their man.

This is not only a prime example of the American police procedural but could serve as a historical text book for today’s crime writer.

New Year’s Resolution

I long abandoned the practice of making New Year’s Resolutions for the spirit, as well as the flesh, is weak these days. There is one thing I am resolved to do, however, which is to go and see – yet again – the wonderful theatrical spectacle that is Patrick Barlow’s version of The 39 Steps, which is touring the country next year.

Based on John Buchan’s famous novel, or rather Alfred Hitchcock’s famous film of Buchan’s famous novel, the production features four actors playing over a hundred different roles including, if memory serves, the actual Forth Bridge.

It’s hysterically funny, and I’m not just saying that because, as an actor, Patrick Barlow appeared in an episode of LovejoyI wrote in the last century.

The one piece of new crime fiction I am planning to read on the first working day of the new year (because it’s published by Headline on 2nd January) is The Broken River by Chris Hammer, who has carved out a well-deserved reputation as a master of the small-town (Australian) mystery. Some years ago, the talent he displayed in his debut Scrublands, was spotted in the much-lamented Getting Away With Murder column.

CrimeFest Finale

When I heard the shock news that CrimeFest 2025 was to be last hurrah for this super-friendly crime fiction convention, I hurried to London to rally the troops, or at least my old chums Peter Guttridge and Ruth Dudley Edwards, to raise their morale and to commit together to making the last Crimefest a memorable one.

I had no need to fear their loyalty – Ruth has attended just about every CrimeFest and Peter’ infamous crime-based pub quiz is the traditional start to the convention. For me, it is an anniversary of sorts, as it will be eleven years since I first appeared on a panel there.

Chaired by my young apprentice, Jake Kerridge, of that once great newspaper the Daily Telegraph, the panel discussed the pros and cons of being a ‘continuation’ author, that is continuing the adventures of an established character in crime fiction. I was there on behalf of Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion, whilst Jill Paton Walsh represented Lord Peter Wimsey, Sophie Hannah bigged-up Hercule Poirot and Robert Ryan spoke for Dr Watson (without Sherlock Holmes).

I am looking forward to chatting to one of the other delegates to CrimeFest 2025 in Bristol in May, whom I have not seen for a while, John Harvey. Before embarking on his first-class ‘Inspector Resnick’ series of crime novels, John had a varied and prolific writing career and I am particularly keen to discuss some of his early novels where, one might say, he earned his spurs. These are being released by our own editor's digital publishing outfit aptly named, Piccadilly Publishing.

Christmas Quiz

I am told that no festive edition of anything is complete without either a guide to the best wines under £8.50 in Aldi, or a quiz. So here’s a quiz question, which was generously donated to this column by James Price, son of author Anthony. (So there just might be a spy-fiction connection...)

This is supposedly the London home of which fictional character? Answers to be chalked on a nearby tree, Moscow Rules apply.

Have a great Christmas

but just remember:

It’s a Jingle out there.

The Ripster.