War Stories (DO Mention the War)

I have long been fascinated by the influence of World War II on British thriller writers, but have finally abandoned my campaign to influence commissioning editors in the subject. I will instead share a few of my early thoughts through this occasional column and highlight novels written before, during and after the war.

I will concentrate mainly on British thrillers because that is what I was brought up reading (with some notable exceptions) and thrillers rather than straightforward war stories, however thrilling they may be. To give an example, I would class Alistair MacLean’s HMS Ulysses as a superb war story, whereas his South By Java Head is a thriller. Several will be better known as crime or detective fiction, but as author Graham Hurley (whose work will get very honourable mention in a future column) has said: WWII was the biggest crime scene in history.

My basic rule-of-thumb is that these ‘revivals’ have a wartime setting rather than flashbacks to the war or a plot which revolves around a wartime experience or incident.

Well. if not actually under fire, at least written and published during the war, featuring spies, amateur detectives, secret agents, policemen, at least one vicious anti-hero and any number of nasty Nazis. And this is only the first instalment. I have NOT forgotten – would I dare? – Ambler, MacInnes, Allingham et al but will be mentioning a few who have, perhaps blissfully, been forgotten.

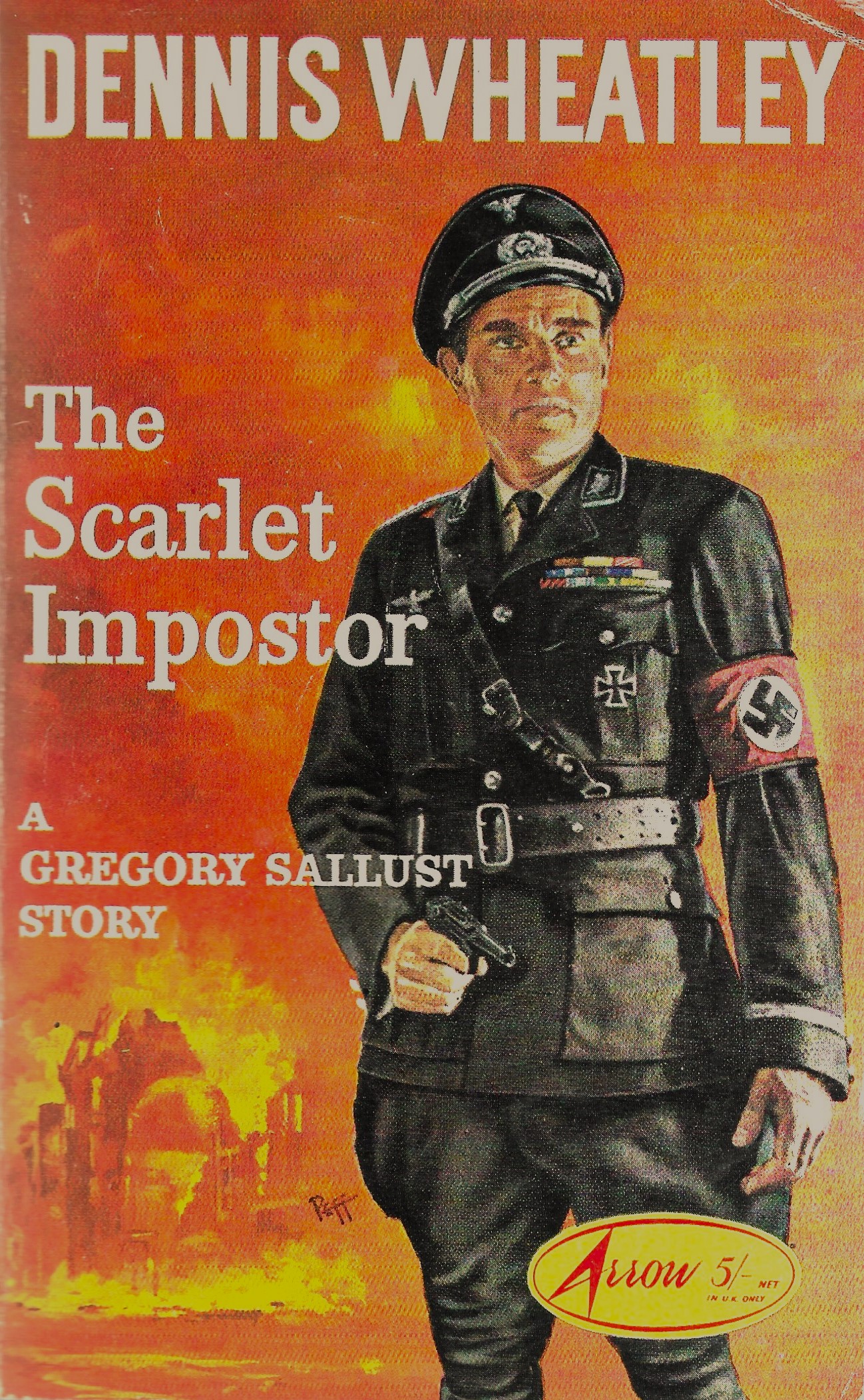

DENNIS WHEATLEY – The exploits of Gregory Sallust

It’s fair to say that I learned, as a schoolboy, more of the military history of the early years of the war from the Gregory Sallust stories of Dennis Wheatley than I ever did in a classroom. In a way it was unavoidable as the four Sallust thrillers published during the war were crammed, positively stuffed, with chunks of analysis of the political and military situation at the time of writing. Novelist Howard Spring likened them to contemporary newspaper reportage as dramatized by Alexander Dumas.

‘Before there was James Bond, there was Gregory Sallust’ wrote Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Tina Rosenberg, and she is not the only one to make the comparison. Sallust – lantern-jawed with a scar above his left eyebrow giving him a cruel, slightly devilish look – is a 39-year-old adventurer with (limited) private means and as WWII breaks out finds himself too old to be ‘called up’ and furious at not being able to see some action; I’d fight the Jerries again for the fun of the thing but these Nazi swine make me see so red I hate their very guts.

Dennis Wheatley (1897-1977) was, like his hero, feeling left out of things when the war came. Already a best-selling author, said to have earned the modern equivalent of $1,000,000 in 1938, and tagged as ‘The Prince of Thriller Writers’, Wheatley was anxious to do his bit for the war effort and so put his imaginative talents to work drafting plans for the conduct of the war (some perceptive, some pretty daft) and sending them, unrequested, to anyone he thought in a position of influence. He also began to write the wartime adventures of Gregory Sallust to boost public morale as well as his sales, beginning with The Scarlet Imposter in 1940, rapidly followed by Faked Passports, The Black Baroness and then V For Vengeance in 1942.

Each novel contained a detailed running commentary on the progress of the war, including the Norway campaign and the fall of France, but really concentrated on Gregory’s efforts, often disguised as a German officer, to bring down the Nazi regime single-handed. Sallust was not, however, a professional soldier or spy, rather he operated as a secret agent under the direction and mentorship of Sir Pellinore Gwaine-Cust, a well-connected patriotic aristocrat with a very extensive wine cellar.

Gregory Sallust’s wartime escapades saw him infiltrate, sometimes with suspicious ease, the highest echelons of the Nazi regime in occupied Europe, his path invariably crossing that of beautiful women and his nemesis, Obergruppenführer Grauber, but the series came to a halt in 1942 when Wheatley was recruited on to the Joint Planning Staff with responsibility for deception plans in the run-up to D-Day. It was a role which would surely have brought him into contact with Ian Fleming and later give rise to much speculation on the similarities between Sallust and Bond.

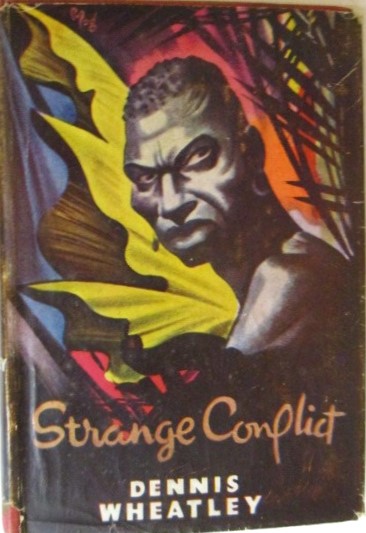

Not content with writing about the war on land, Wheatley moved on to the ‘Astral Plane’ with Strange Conflict in 1941, which saw his heroes from pre-war books, led by the Duc de Richelieu (famous from Wheatley’s bestseller The Devil Rides Out), battling Nazi occultists using black magic and voodoo to locate Allied convoys in the Atlantic. One wonders what those bright young men and women at Bletchley Park would have made of the intelligence thus gathered.

Sallust’s wartime career was concluded in novels which appeared after the war had ended, climaxing with a final bestseller in 1964, They Used Dark Forces in which Gregory teams up with a powerful Satanist firstly to sabotage the V2 rocket programme then, with a little help from Reichsmarshall Goering (!), to infiltrate a certain Berlin bunker, coming face-to-face with Adolf Hitler and gently persuading him to commit suicide.

Interestingly, in a prologue in the form of a letter from ‘Gregory’ to ‘Dennis’, Sallust has no doubt that the author will write a spy story to top all spy stories, which is strikingly similar to something Ian Fleming said before writing Casino Royal. Coincidence? Probably.

AGATHA CHRISTIE – N or M? (1941)

Agatha Christie continued to write murderous mysteries throughout the war, most famously Curtain, Hercule Poirot’s final case, which was locked away and only published in 1975, but the book which was clearly inspired by the war was N or M? featuring her dynamic duo Tommy and Tuppence Beresford.

Written in 1940 with the promise of a lucrative serial deal in the USA, the Beresfords, now too old for front line espionage work, have to settle for going undercover in a genteel south coat boarding house to unmask two of Hitler’s top agents (where else would they be?) bent on establishing a Fifth Column in England prior to a Nazi invasion.

When the American editors of the magazine which had promised serialisation read the story they withdrew their offer, claiming that such a strongly anti-Nazi stance would ‘upset a substantial section of their readers’. Agatha was rightly furious and insisted on publication of the book in 1941.

At the time of writing N or M?, Agatha, at the age of fifty, was feeling, like Dennis Wheatley, frustrated at not being able to contribute more to the war effort. She makes this clear by having Tuppence’s daughter describe her mother as rather ‘hipped’ and feeling her age because nobody seemed to want her in this war. Of course, she nursed and did things in the last one – but it’s all quite different now, and they don’t want these middle-aged people. They want people who are young and on the spot. Dame Agatha had of course nursed and done things in the first world war.

At first the war seems to have little impact on life in the boarding house where Miss Marple would surely have felt at home. Tuppence, posing as a Mrs Blenkensop, sits knitting balaclavas for the troops while Tommy gets in a few rounds of golf. The question is which of the people they are mixing with are the Nazi agents? The Beresfords go about their investigation with their usual “intolerable high spirits” as Christie fan Robert Barnard wrote, concluding that the book was “Less racist than (her) earlier thrillers...but no more convincing.” (At one point, Tommy – bound and gagged by Nazi sympathisers – manages to summon help by snoring an SOS in Morse Code!) Christie’s biographer Laura Thompson is more generous, calling the book an “undervalued wartime thriller with Tommy and Tuppence at their most bearable.”

The dramatic highlight of N or M? is a cliff-top scene where a distressed woman holding a small child moves perilously close to the cliff edge. She is shot ‘in the head’ and the toddler saved. There is (naturally) no blood, spattered brains or even screams from the onlookers and nobody suggests therapy for the child. It is a cold, callous piece of action which, [spoiler alert] given the identity of the shooter, is perhaps exactly what it was intended to be.

There is also a final reveal in that one Fifth Columnist has been under the noses of the Beresford family for some time.

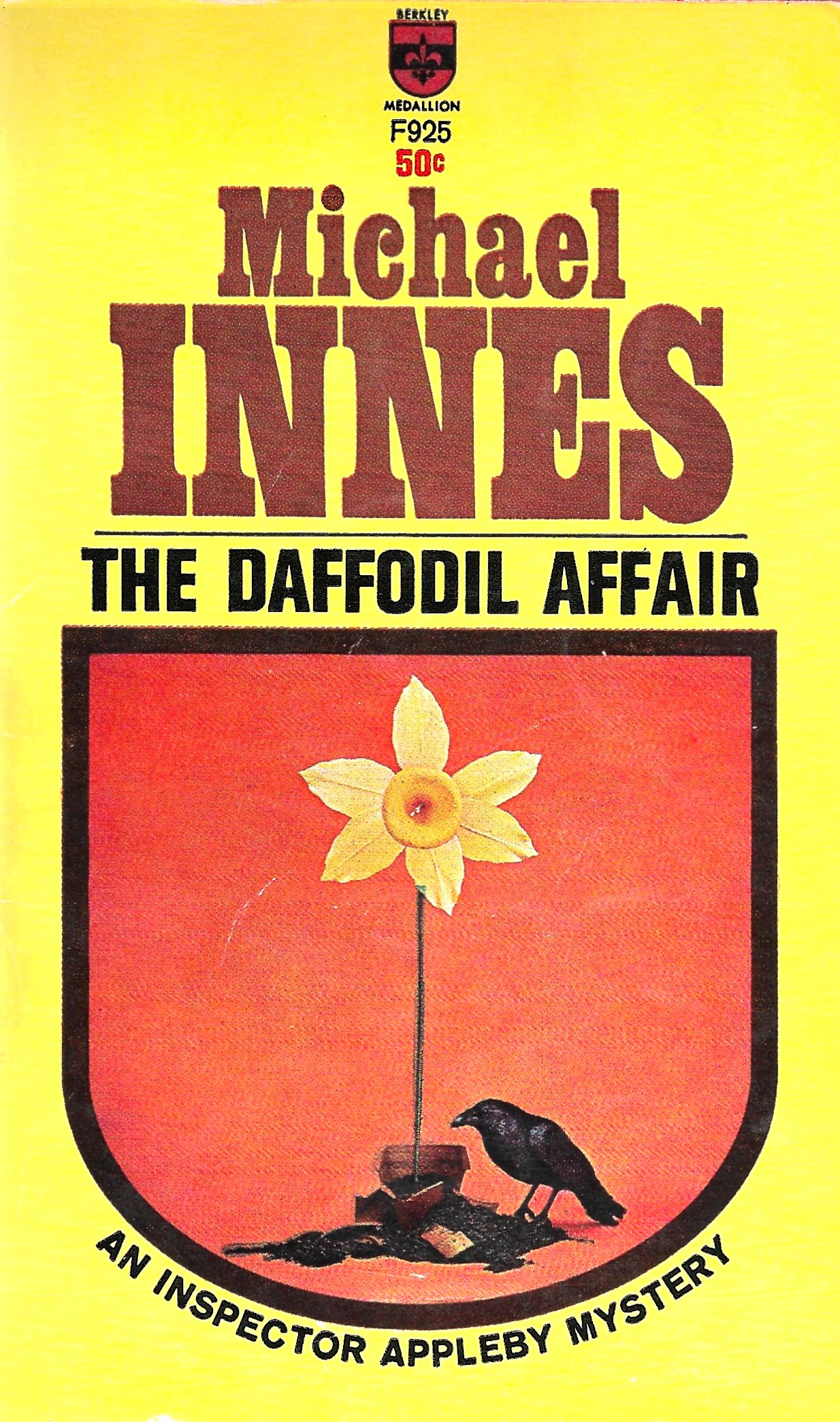

MICHAEL INNES – The Daffodil Affair (1942)

Like Agatha Christie, Michael Innes kept writing detective stories throughout the war years, but he and his detective hero tackled the wartime environment as only Michael Innes and Inspector John Appleby could, which is to say with flights of ridiculous fantasy, tons of literary references and great dollops of donnish humour.

The donnish humour should come as no surprise as the pen-name disguised the identity of John Innes Mackintosh Stewart (1906-1994) whose academic career included posts in universities in Leeds, Adelaide, Belfast and Oxford. His early detective novels featuring Inspector John Appleby (later to become Sir John and Commissioner of the Met) were all written while working in Australia, where he spent the war years, so he was hardly in a position to paint a gritty picture of an England under siege; but then a Michael Innes story was never likely to do that.

In The Daffodil Affair he suggests that ‘England today [1941] is a country in which even slightly mysterious manoeuvres are singularly difficult to perform’ which turns out to be something of an understatement as the plot involves the disappearance of a young girl said to be psychic, various items associated with an eighteenth-century Yorkshire witch, a horse called Daffodil which can do basic arithmetic and an entire London house said to be haunted!

Bizarrely, Innes offers an almost* credible explanation of how an entire terraced house could disappear in wartime: it was dismantled and smuggled out of the country disguised as rubble from a Luftwaffe bombing raid to be used as ballast in ships bound for America where it would make the foundations of new docks and quays.{* As the author adds: a sober fact so fantastic that one would hesitate to put it in a magazine story.}

The pursuit of all this paranormal paraphernalia involves Appleby and a colleague in a long sea voyage across the South Atlantic in the company of some dubious characters who would clearly be thuggish villains had they not been able to swap literary references with Appleby, who is never slow in coming forward on that score. Their journey ends with them as prisoners in a lavishly appointed jungle colony somewhere up a river in Brazil or Argentina (it doesn’t really matter). The colony is the brainchild of a super-rich madman who aims to corner the market in everything psychic, as he predicts a boom in seances and occultism after the war – just as there was after World War I.

Gradually, in this very civilised prison, guarded by jungle, swamp and crocodiles, Appleby realises that psychic experiments are going on and he is to be part of one. ‘I’m being murdered to further the purposes of psychical research; murdered in order to manufacture a ghost.’

This leads to a reflection on detective stories, where hundreds of authors (mostly men, but ‘a couple of women are excellent’) are basically searching for an original motive for murder and surely being murdered to produce a ghost is pretty original.

His fellow prisoner dismisses the suggestion: ‘We’re in a sort of hodgepodge of fantasy and harum-scarum adventure that isn’t a proper detective story at all. We might be by Michael Innes.’

To which Appleby replies with a sigh: ‘Innes? I’ve never heard of him’.

The Daffodil Affair is an imaginative, phantasmagorical exercise written in Mandarin prose and littered with erudite literary quips, on which the war barely impinges, a blend of fantasy and melodrama. As a thriller, it has its tongue firmly in its cheek and not for nothing did the critic Julian Symons call Michael Innes the leading farceur of crime fiction. It was a label Innes seems to have approved of and which probably prompted some chuckles of admiration at High Table.

JOHN MAIR – Never Come Back (1941)

Cynically one might say that the reputation of Never Come Back rests on a very positive pre-publication review by George Orwell (‘This is an amusing book’) and reverence to it by the literary establishment rather commercial sales (it went out-of-print for long periods, though a new edition was published in 2017, seventy-five years after the author’s death). Its adaptation as the 1955 film Tiger by the Tail and as a three-part BBC drama serial in 1990 seem to have done little to increase its reputation. It is, however, something of a one-off; quite literally.

Never Come Back was the only thriller of John Mair (1913-1942), a literary critic and book reviewer, determinedly liberal and anti-fascist in the 1930s as well as a keen gambler (poker and greyhound racing). He has been described both as charismatic and dogmatic. He wrote Never Come Back whist waiting his call up into the RAF where he was commissioned as a Pilot Officer and died during a training flight in 1942.

It is said that the book featured the first true anti-hero, journalist Desmond Thane, who certainly goes out of his way not to make friends with his readers, let alone his fictional adversaries. Thane is vain, callous and often cowardly and shows absolutely no remorse after beating up and then murdering his mysterious lover (God knows what she saw in him), who turns out to be a secret agent in the employ of International Opposition.

As if there weren’t enough villains around in 1940, Thane is then pursued by agents of I.O., ‘a federal union of the dispossessed’ wanting to restore genuine Bolshevism to Russia, genuine National Socialism to Germany (one of the ruling cabal is a member of the Gestapo!) and benevolent autocracy to England. This seemingly powerful SPECTRE-like organisation in fact turns out to be no more effective than a disgruntled Tunbridge Wells Rotary Club, but it does employ some professional thugs to hunt down Thane who has stolen of a list of their contacts.

Thane is chased, captured and tortured and one of his main tormentors is described thus His face was clever, and like that of so many outwardly lush Jews, curiously austere and he is referred to simply as ‘the Jew’ for the next sixty pages (until Thane kills him), which sits rater uncomfortably with the modern reader. In the chase/escape/pursuit scenes one can certainly detect the influence of John Buchan and Hitchcock’s film of The 39 Steps and perhaps that’s the point; the awful Thane being the polar opposite of the steadfast and upright Richard Hannay.

There is a sense of Thane’s paranoia, though at times – particularly in fantastical scene at a carnival on Hampstead Heath – he doesn’t seem bothered at all, and you never get the feeling that the dreaded International Opposition are a threat to anyone else. The war itself is only an occasional backdrop to the story, which doesn’t seem to hinder Thane taking taxis around the pubs of London, to his club, or when picking up women and the black out and the distant sound of anti-aircraft guns are mentioned only once and very late on.

I get the feeling that Mair was trying to write a thriller as burlesque, and also that he was getting in a few digs at some of his contemporaries on the literary acene. Is it the ‘anti-fascist tract’ which the critic Tim Heald called it? I’m not so sure. I think Eric Ambler nailed that attribute.

J. B. Priestley - Black-Out In Gretley (1942)

John Boynton Priestley (1894-1984), novelist, playwright and social commentator would, in today’s parlance be a national treasure if only for his popular, morale-boosting radio broadcasts during the war. There again, he would probably be accused of being a left-leaning member of the BBC wokerarti. He was never, to my knowledge, accused of being a writer of spy fiction, but during the war he gave it a go.

Black-Out in Gretley is the story of MI5 officer Humphrey Neyland, the five-foot eleven, pipe-smoking (and there is a lot of pipe smoking) hero who is sent to the grey Midland town of Gretley to uncover a nest of Nazi spies. He does this by smoking his pipe a lot, kissing every female in the place (there is a lot of kissing) and being “sour”, which I think is Priestley’s way of trying to indicate that he is a cynical, wise-cracking Philip Marlowe type. The only problem is that apart from the pipe-smoking, the similarities end there.

We are never really told why there should be a nest of Nazi spies in Gretley or why they seem to be operating out of a nick-knack shop and the local Variety Hall; and Neyland’s method of spy-catching is straight out of the pulp ‘private eye’ handbook. Which is to say he does virtually no detecting as such; he just turns up (in pubs, in boarding houses, in restaurants, in a doctor’s surgery...) and wherever he is, people instantly tell him things, some of which are actually relevant to the plot – if ‘plot’ isn’t too strong a word.

None of the women in the book can resist being kissed by Humphrey (though what that must have been like given the number of pipes he smoked...) and every scene is top heavy with dialogue, with little description and even less action, though there are two ‘off-stage’ murders and a shoot-out finale of sorts.

Any reader with modern, politically-correct sensibilities, is unlikely to make it as far as the ‘a lot of shots rang out’ denouement, being put off by early references to a pansy with rouged cheeks, people working “like blacks”, a Musical Hall comedian who “works like a nigger” in his act, and a chorus line of dancers referred to (many times) as the “platinum Jewesses.”

I hadn’t realised, until I looked it up, that Evelyn Waugh was very scathing of the book at the time of publication. I was, however, aware that Priestley attempted to take legal action against Graham Greene, having felt himself lampooned in Greene’s Stamboul Train in 1932. All in all, I don’t think Priestley had a happy time with the thriller genre.

H.V. MORTON – I, James Blunt (1942)

I was told of this short novella by Len Deighton in a discussion about his novel of a Nazi-occupied England, SS-GB, and with some difficulty managed to find a copy.

Written as a propaganda warning that the war was far from won (and published the same year that saw the release of the marvellous film Went The Day Well?), I, James Blunt takes the form of the secret diary of widower James Blunt, living in leafy southern England and quietly resisting the none-too-subtle attempts to "Germanise" the population, five months after Britain has capitulated.

Blunt’s diary begins in in September 1944 and ends dramatically in March 1945 and what comes through most powerfully is the paranoia about whether one can trust one's neighbours, or even one’s own family under the new regime. There are chilling references to Blunt’s grandchildren now being ‘educated’ under the Nazis and a local schoolboy who reports his own father for ‘hating Hitler’. The diary is restrained and understated, which emphasises the horror of the situation, the warning being: it could happen here in dear old England.

Henry Vollam Morton (1892-1979) was a national newspaper journalist who turned to travel writing with great success in the 1920s and 30s, earning him the title ‘world’s greatest living travel writer’. His most famous book was In Search of England published in 1927 (with a new edition in 2000) and sales of his travel guides were numbered in millions, reputedly earning him £30,000 a year by 1939. A 21st-century biography of Morton has apparently found evidence of pro-Nazi sympathies in the 1930s, but in I, James Blunt, his rare foray into speculative fiction, it’s pretty clear which side he’s on.

Previous RIPSTER REVIVALS:

#1: PETER DICKINSON (and Jimmy Pibble)

#2; DAVID DODGE

#3: NEVIL SHUTE