|

Ripster Revivals #1

Fair enough, this is a bit of a vanity project, but the Editor of Shots agreed to it months ago in order to keep me quiet and off the streets after my retirement from the Getting Away With Murder column. It is not a ‘bucket list’ rather an occasional series of essays featuring books – crime novels and thrillers – which I have been meaning to read, or re-read for, though I hate to say it, up to fifty years or more. Finally, without the pressure of having to consider the hundreds of new crime novels being churned out week after week, I have the time and the incentive and I know I will become reacquainted with some favourite authors and almost certainly discover new ones.

I expect there to be surprises and disappointments along the way, but if I can bring one forgotten author to the attention of a new audience, or convince a single reader that good thrillers existed before mobile phones, then it will have been worthwhile.

|

Peter Dickinson (and Jimmy Pibble)

I had heard of Peter Dickinson long before I ever read one of his award-winning crime novels, because the author was, if anything, more famous for the awards he had won rather than the books which won them.

Back in the late 1980s, as an innocently enthusiastic new member of the Crime Writers’ Association and the freshly-appointed crime fiction critic for the Daily Telegraph, I began to take an interest in the CWA’s famous ‘Dagger’ awards – a purely academic interest of course as I was never likely to be in contention for one and it was to be more than ten years before I was asked to be a judge.

The name Peter Dickinson cropped up when I read somewhere that he had won the coveted Gold Dagger with his first crime novel, Skin Deep, in 1968. Even more impressive was the fact that his second novel, A Pride Of Heroes, also struck gold in 1969, a success rate no other writer had managed two years running before and was only repeated later by Ruth Rendell and her alter ego Barbara Vine. As I say, I was young and impressionable and having a great time meeting some of my crime-writer heroes and this Peter Dickinson seemed to be a chap worthy of a bit of hero-worship.

Yet when I innocently enquired whether Peter Dickinson was likely to show up at one of the monthly CWA meetings (held, in those days, in The Groucho Club), I was told in hushed, confidential tones that it was unlikely as the general membership had taken a dim view, twenty years before, of the same writer winning the top award two years running. I got the impression, rightly or wrongly, that Dickinson had been snubbed if not shunned and as far as I am aware none of his subsequent considerable output of crime novels over the following forty years were considered for a CWA award, although his 1999 Some Deaths Before Dying would have been a favourite for a third Gold Dagger according to some critics, me included.

Whether Dickinson was snubbed by the crime-writing establishment or not, it did not dent his simultaneous second literary career as an author of what today would be called Young Adult fiction, much of it steeped in fantasy and history. That career brought him multiple further awards, including the prestigious Carnegie Medal, which he won twice in successive years, 1980 and 1981, repeating his Gold Dagger achievement.

There was a fantasy element in much of his crime-writing, the ability to take the essence of a traditional English murder mystery and then add a fantastic or surreal element. It was a unique, unclassifiable approach which made Dickinson difficult to compare with any other crime-writer – perhaps Michael Innes at his zaniest comes closest – and one distinguished student of crime fiction, Mike Ashley, labelled him ‘the 20th century’s Lewis Carroll of mystery’.

His debut crime novel, Skin Deep, which is a very appropriate title but nowadays the book is much better known for its American edition as The Glass-Sided Ants’ Nest, launched the career of Dickinson’s series hero Detective Superintendent Jimmy Pibble.

Pibble is not the conventional policeman, or perhaps he is, it’s just his cases tend to be unconventional. He refers to himself as ‘the ex-coming man’ and even a minor local crook recognises in Ants’ Nest that it is a ‘kinky little case’ and that Scotland Yard ‘wouldn’t send one of their big boys out on it – too much to lose, nuffing to gain’. Pibble privately agrees with the sentiment; ‘kinky and little’ being just his line and suited to his talents ‘whatever Mrs Pibble might say’ though Mrs Pibble seems to be a mental distraction for our gentle copper hero and rarely a physical presence.

On the surface his first case provides so many distractions, domestic ones hardly matter as there’s quite enough going on a it is. A man is murdered in a London terraced house and Pibble does not even raise an eyebrow when he is told that the murder weapon was an owl (a wooden one), as that is the least strange thing about the house.

The murder victim is an elder of the survivors of a tribe of New Guinea natives who fled from the Japanese during World War II and thanks to the anthropologist who wishes to study them, are now encamped in the top floors of a suburban house – the glass-sided ants’ nest of the title – following their traditional rituals and ceremonies although a couple of the men have had to take jobs with London Transport. To simplify matters, they’re all called Ku, as is the tribe, even the tribe’s mentor who shows her commitment by agreeing to a homosexual marriage. (Not what you think.) There are rituals including bowls of blood and constant drumming and the tribe takes a joyful delight in misleading Pibble at every turn in his enquiries. There is also a brutish, philandering neighbour with distinctly shady connections to the tribe, whom Pibble really hopes is the murderer but isn’t (not a spoiler).

On several occasions, Pibble enjoys becoming distracted from the meat of his investigation. Always a bit deficient in the hunting instinct – more of a herbivore than a carnivore, as detectives go – this time he simply didn’t care whether anyone was arrested or not. Interesting setup, of course; curious people. That was part of the trouble: it was only a sort of scholarly inquisitiveness that kept him asking questions and nosing about; the purpose behind the questions seemed increasingly irrelevant, the murder-hunt a distraction from the real thing.

Life, and police work, does not get any easier for Pibble in his following cases, A Pride of Heroes (1968) and The Seals (1970)

In Pride of Heroes (also known as The Old English Peep Show), Pibble finds himself wandering around a Georgian mansion with a bucket of animal dung trying to avoid a man-eating lion almost as if it is all in a day’s work, In The Seals (aka The Sinful Stones) he finds himself isolated on a remote Hebridean island where a 92-year-old Nobel prize-winning scientist is being held against his will by a militant religious community attempting to build a new Jerusalem.

Critics on both side of the Atlantic drooled over Dickinson’s imagination and distinctive style putting him ‘streets ahead of others for interest and ingenuity’. In America, his novels were endorsed by both Ross Macdonald and Ross Thomas, whilst in England he was described by Francis Iles as ‘the most original crime novelist to appear for a long, long time’, by Anthony Price as ‘hard to beat for [a] remarkable combination of elegance, whackiness and excitement’, and Edmund Crispin made the obvious comparison ‘the best thing that has happened to serious, sophisticated, witty crime fiction since Michael Innes’.

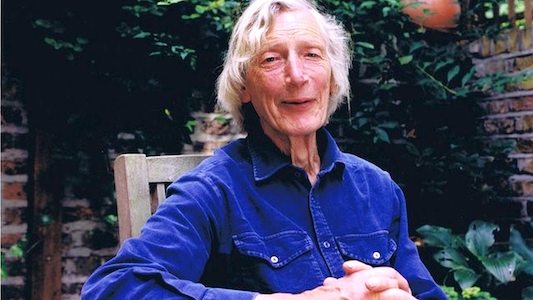

Peter Malcolm De Brissac Dickinson, O.B.E. (1922 -2015) no doubt honed his sense of humour working for Punch magazine, contributing poems and reviews of crime novels, before becoming a full-time author. From his writing (not always an accurate character guide), I suspect he was good company. Certainly, he was much admired by the critics and popular with his multiple audiences and today is probably best remembered as an author of Children’s books or Young Adult fiction and his reputation as a crime writer may have faded.

Dickinson’s highly imaginative style and highbrow humour might not be to everyone’s taste and certainly his debut novel would raise a politically-correct eyebrow or two among today’s young editors for whom 1968 is an undiscovered country. Several words beginning with ‘N’ would no doubt be redacted along with references to western oriental gentlemen.

Re-discovering Peter Dickinson and Detective Superintendent Jimmy Pibble was, for me, a treat. In an output of more than fifty novels over several genres, only half-a-dozen were Jimmy Pibble adventures, so re-reading them has not been too difficult. My problem is that it has given me an overwhelming urge to re-read all the Inspector Appleby novels of Michael Innes, and I think I have twenty-three of those...