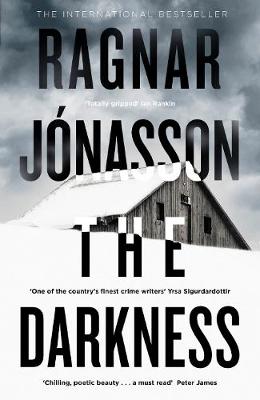

Ragnar Jonasson's

most recent novel, The Darkness, was so impressive that I worked on

arranging an interview from the moment I knew I was visiting Iceland. We met at

his office, in an impressive but unimposing house just off the centre of

Reykjavik. Inside, it's been converted into a slick modern headquarters for an

international investment firm, for whom Jonasson is a lawyer in his day job. This

was a pleasant Icelandic summer day in August, some sunshine, temperature in

the high teens celsius. Of course in Iceland when you have a day job, the days

are very long in summer and very short in winter. Which is why my first

question was how he managed to balance his high-powered day job with his steady

output of novels. The interview has been edited slightly to avoid spoilers,

given that the finish of The Darkness is so powerful.

RJ:

I write every night in the winter, which gives me enough time to finish a

novel. It's like a hobby, like some people go hiking, or watch TV. I plan one

book a year, and in Iceland the big publishing date falls before Christmas,

because books are a traditional Christmas present here. Sometimes I'm tempted

to do more, but I really like being a lawyer, and if I did have more time free,

much of it would likely be spent marketing my books, not necessarily writing

more.

MC:

You started writing professionally at a very young age, translating Agatha

Christie. How did that come about?

RJ:

I needed a job for the summer! Christie had been well-translated into Iceland,

but I discovered there were quite a few works still out there, and I liked

them. I starting translating short stories for magazines, and did it for 10-15

years, again like a hobby. Then the crime-writers who came before me started to

make Icelandic crime a lively genre and proved it could be done. So Icelandic

readers learned to like crime fiction, but it needed to be a believable story

when you're set in a small country where there aren't as many crimes.

MC:

Indridason, for example?

RJ:

Yes, of course, and it was very interesting how he began by using a situation

which depends on Iceland's being an unusual country.

MC:

What drew you to Christie specifically? Because your 'Dark Iceland' series is

very much in the Christie tradition.

RJ:

I love the classic set-up, a limited number of suspects, but you have to do

something with it—it would look awkward if you copied the settings and

characters.

MC:

But there are similarities in the societies, from what I've seen.

RJ:

Iceland is a very closed and stratified society, which is more obvious in small

communities, which is part of why I set the series in the north. It's about a

close community, nature and the landscape, and the weather. I'm blessed with

having this strange country to work with.

MC:

Having looked at the old law site at Pingvellur, I wonder if it's a judgemental

society too?

RJ:

Certainly in the old days. I'm not so sure it's still like that, because people

do try to stick together.

MC:

You see some tension in your characters, the way Ari Thor is relatively simple

and straightforward, somewhat traditional, where his girlfriend Kristin is more

modern in many ways.

RJ:

Ari is a bit shy, with a sort of closed-off life and personality, like many

Icelanders are, so his personal life can have problems. But the crimes he

investigates are the kinds where that personality allows him some leeway in

getting to the solutions.

The Darkness

features a new detective for Jonasson, Hulda Hermansdottir. She is a dedicated,

hard-working, old-fashioned kind of cop, who has been passed over for

promotions partly because she is a woman and partly because that doggedness

doesn't always fit in, when she won't play the office political game. Now she

is being pressed into unwanted early retirement, and to get her out of the way,

she's offered one last cold case to choose to investigate. It involves the

death of a young Russian woman, found on the coast, and ruled suicide. But that

doesn't sound right to Hulda...

MC:

I heard you interviewed on BBC Radio 4's Front Row (full disclosure: a

programme to which I am an occasional contributor) a few months ago after The

Darkness was published in hardback, and although it was an interesting

discussion of reading and publishing in Iceland, I was shocked because they

never once asked you about your novel!

RJ:

Well, I was very happy to talk about my country, and we are a very literate

society. But yes, to talk about my book would have been nice.

MC:

I thought The Darkness was one of the very best novels crime novels I

read last year, and what I particularly liked was the way it ends. I had the

same sort of 'you can't do THAT!” reaction I had when I read Joe Gores'

Interface: you've played with the genre's conventions brilliantly.

RJ:

Thank you! That was both deliberate but also how the story itself grew. I had

an idea I could work backwards, because I knew from the start it was the only

way I could end the book. I know the ending may come as a surprise, in fact I

expected it, but it was really the only logical way it could end. It was so

powerful. The reaction in Iceland wasn't so risky, because you can do more

because the crime-writing tradition has been going only a short time. But

outside Iceland it was more of a challenge to break the rules, so to speak, but

it was a challenge I had to take.

MC:

Especially because your earlier books are so relatively traditional?

RJ:

You really do want to challenge the form. You know the rules, and you want to

break them in your own way. That was always my intention.

MC:

And it is somewhat judgemental.

RJ:

Yes, there is a price to pay in the end. You cannot go back. Back in the early

centuries of this state there was no police. Which sometimes means individuals

feel they have no choice but to act.

MC:

You establish a great deal of sympathy for Hulda.

RJ:

Which made many readers almost angry at the way the story progressed. They

liked her, and I loved that reaction. But I'm working on two more novels

featuring Hulda, which go back into her early career.

MC:

How do you work The Darkness into that?

RJ:

They won't give away the twists of The Darkness, but I think to those

who've read the first book, it will provide added value to understand that. A

deeper meaning, if you will. And I've started the next Dark Iceland novel. I

already knew the plot for that one.

MC:

It will keep you busy.

RJ:

I wouldn't feel comfortable any other way!

Ragnar needed to get back to work, as

calls were literally lining up while we spoke in the conference room, but

before he did I told him I particularly loved the very last scene of The

Darkness, a coda of sorts which is seeped in a kind of polite authoritarian

hypocrisy, but also reminds us of how, even in a small, closed society, we may

know very little about each other. He thanked me, and I thanked him for his

time. Two days later, as my plane left Iceland I looked back at the island and

thought just how powerfully and subtly Jonasson had interpreted his society.

And how unexpectedly.

The Darkness, translated by Victoria

Cribb, is out in paperback now from Michael Joseph.