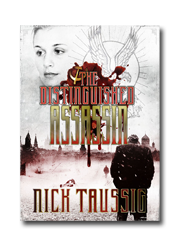

Shots: Welcome, Nick Taussig, to Shots Magazine, and congratulations on your latest novel The Distinguished Assassin. This remarkable book takes us into the heart of Stalin’s Russia between 1949 and 1955, when the dreaded labour camps were in force and for many, even on the outside, life was tougher than anything we in the west can possibly imagine.

When central character, former soldier and academic, Alexei Klebnikov is ripped from his family and thrown into a camp on false charges, he finds himself given an option by a major criminal leader for getting out alive: he must kill six important communists whom the gangster, Ivan Bessonov, says are evil and corrupt.

As a first question, your descriptions of the conditions in the camp are truly vivid. As far as treatment by guards and fellow prisoners of the weaker inmates, and the whole regime goes – how did you research this detail? Did you talk to former inmates?

NT: I only managed to talk to a few former inmates, and these inmates were not imprisoned under Stalin, but Khrushchev and Brezhnev, when things had eased a little. Most of it came from three books in particular, Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales and Anne Applebaum’s Gulag. The first is a brilliant piece of non-fiction, if anything for the sheer extent of its detail. And the last, an extraordinary first-hand account of life inside. Shalamov had to ensure the very worst that Stalin had to offer, a labour camp in Kolyma, andhis writing, particularly about the urki (the career criminals) is grim but captivating.

Shots: On a similar issue, a lot has been written over the years about the Russian gangs and their particular ethos and customs, especially the rigid rules existing within the organisations. Are your characters based on any specific figures?

NT: I got a little hooked on the research of the gangs. The idea for the novel came after watching Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises, a great tale of a good man gone deep cover to tackle the vory v zakonye (the thieves-in-law). I was fascinated by this elite criminal society’s rules and customs, which even renounced romantic love and family, and how it managed to thrive under Communism - no surprise, as there was such a thriving black market. I read a number of non-fiction books on the Russian mafiya, including Stephen Handelman’s Comrade Criminal. However, this was about the vory in post-Soviet Russia, so I was free to interpret and imagine quite a bit, though Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov proved themselves invaluable here too.

Shots: Watching Alexei’s progress through the book is like observing a car crash in slow motion. How did you manage to control the pace of events without letting it run away with you?

NT: There’s a quote that stayed with me throughout the writing, from Solzhenitsyn. It’s long, apologies: ‘A human being hesitates and bobs back and forth between good and evil all his life. He slips, falls back, clambers up, repents, things begin to darken again. But just so long as the threshold of evil doing is not crossed, the possibility of returning remains, and he himself is still within reach of our hope. But when, through the density of evil actions, the result either of their own extreme degree or of the absoluteness of his power, he suddenly crosses that threshold, he has left humanity behind, and without, perhaps, the possibility of return.’ I wanted Aleksei to be a tragic hero, very much in the Russian tradition. He had to fight, wrestle with his soul, bob back and forth between good and evil, but ultimately be condemned. To this extent, the drama had to lie in his long hard struggle, his battle with his soul, not the novel’s conclusion.

Shots: In Alexei, you have an academic who agrees to kill six men – plus one choice of his own for extremely personal - and understandable - reasons. Part of his thinking is that he despises people in positions of power who abuse that power. Do you think that feeling was common in many Russians – both then and today?

NT: A very good question. The Russian soul gravitates towards authority. There’s even the view that it’s predisposed to authoritarianism. This I do not believe, and yet, one cannot escape the fact that the Russian people, with figures such as Stalin and now Putin, do have a strange relationship with authority. They want their country to be great, and this requires strong leadership, so even if they must then sacrifice some freedom and happiness to attain this greatness, they are willing to.

Shots: There’s an undercurrent of dark humour in the book – especially among the labour camp inmates. Do you find it easy to include this element as part of your writing toolkit, or did you have to force the issue here, given the background?

NT: Without the humour, it simply would have been too bleak and depressing. I had an earlier draft which had little, and after fifty pages of misery the reader would surely have had enough, I thought, and rightly so. Better then to read non-fiction. There’s also truth in finding humour in darkness. Shalamov, in spite of his many years of incarceration, possessed a dark humour throughout.

Shots: Does your own background include any useful insights to the Russian character, or are you writing from a more distant viewpoint?

NT: My grandparents were Czech Jewish emigres, who fled the Nazis rather than the Commies. Had they not fled, and survived the genocide, then they would have lived under Soviet Communism. I felt this very strongly from them, their gratitude for not living under an authoritarian regime, which remains synonymous with Russia even today. I married a Czech woman, who possesses that very Central European character, prone to melancholy and rye humour, like the Russian character, but less tragic and extreme, thankfully.

Shots: You alternate in the book’s chapters between 1949 (prison time) and 1954-5 (outside time). It works extremely well in presenting both parts of this period for Alexei, because for the reader, at least, he is living the two major parts of his life – one in prison, the other after. I wondered whether you had decided on this alternate chapter approach right from the start or did it come later?

NT: No, I hadn’t. This was the work of my editor, who told me that as it read before, in a linear fashion, it was too much a then-and-then story. It was also very hard work for the reader, who needs respite from the labour camp, which offers too much misery and not enough excitement.

Shots: The scenes in this book are very cinematic, which is no surprise, given that your other ‘hat’ is that of a film producer. Do you have to rein yourself in on that descriptive front while writing a book or does the film ‘eye’ control itself?

NT: I must confess that I have to rein myself in. I love reading screenplays for their brevity, and struggle with a lot of fiction, which often, for me at least, feels desperately over-written. Too often I’m thinking when reading a novel, “Just get on with it, will you!” The discipline of film does this to you. It makes you impatient, and if there’s too much set up, and story is put at the expense of scene and mood – a writer losing himself in his descriptive powers – I’ll quickly tire and switch off. I’ve always been one for succinctness, and will always choose a few words over many. I also believe that the increasingly visual culture we live in means that the contemporary reader would rather interpret and imagine than have everything described through endless adjective, simile and metaphor.

Shots: I felt uncomfortably cold all the way through this book (thanks - as if I needed it with the winter we’ve been having). However, our weather can’t possibly compare with conditions in eastern Russia. Have you been there or experienced such extremes for yourself?

NT: Yes, and it’s fucking cold! Minus 50 in Yakutsk in deepest winter. I travelled quite a bit in Russia, even to Magadan, in the Russian Far East, the gateway to Kolyma and former gulag hell. A 9-hour flight from Moscow and you’re still in the same country, despite crossing 8 time zones. And even when I was in Moscow, and it was summer, it felt cold, when it was actually quite warm. The Russian soul even rubs off on the weather, though perhaps this is the other way round.

Shots: Can you give us an ‘elevator pitch’ of your next work?

NT: I’m afraid I don’t know yet. I’m waiting for that spark, that drive.

Shots: Thank you, Nick for your time, and the very best of luck with your books.

You can read more about Nick and his work at http://www.nicktaussig.com

Released June 10 2013 Hbk £12.99 from Dissident Publishing

Read Adrian Magson's Review click here

medical abortion pill online

abortion pill cytotec abortion pill buy online

i love my boyfriend but i cheat

click i want to cheat on my boyfriend

i cheated on my husband and got pregnant

link should i cheat on my husband

temovate tube

click furosemide 40mg

abortion pill costs

fyter.cn walk in abortion clinics

cialis coupons printable

site cialis coupons from manufacturer

free prescription drug discount card

site cialis savings and coupons

claritine d

site claritine d

motilium et grossesse

site motilium enceinte

ventolin prospecto

open ventolini cali

prescription drugs discount cards

evans.com.mx discount drug coupons

amoxicillin antibiyotik fiyat

amoxicillin-rnp amoxicillin antibiyotik fiyat

addiyan chuk chuk

addyi fda addiyar newspaper

naltrexone studies

go low dose naltrexone contraindications