“I hate Agatha Christie so much, I can hardly bear to say the name of that village of hers – St Mary Mead, where that awful Marple woman lives.”

That’s not me.

It’s Ruth Rendell.

“Going back to the hated Agatha,” she went on, “one finds a lot of normal, law-abiding people living ordinary, blameless lives, who suddenly decide to murder their aunt. Well, I don’t believe in that.”

I have a little more equanimity than Rendell when it comes to the Golden Agers, but it has always bothered me that you’d be forgiven for believing that, before a clutch of writers in the sixties, British crime fiction was exclusively about bourgeois dilettantes running about solving the murders of rentiers’ aunts.

Christie was a master at building suspense and crafting classical mysteries, but that was never my thing. I never enjoyed puzzles, even as a child, and have little interest in them as a reader. I’ve always preferred fiction that was about crime, rather than just featuring a crime. Worlds of lowlifes and conmen, or working stiffs battling to get by, living on the margins of crime and poverty. I crave grubby fiction with dirt under its nails, and I write it too.

My new novel, White City, is a fictional retelling of the Eastcastle Street robbery in 1952, at the time the biggest heist in British history. Beginning with the robbery, it traces the cracks that open up in families and communities from such a crime, the precarious lives of the women and children left behind by the men involved. A story of the working poor, of ghettoization and gentrification, of political and police corruption, of hucksters and demagogues stoking racial tensions, until everything comes to a head in the white rage of the summer of 1958 and the riots in Notting Hill.

This kind of social-historical crime writing isn’t unusual these days – think David Peace, or Jake Arnott, or Cathi Unsworth, or Joe Thomas, or countless others – but it wasn’t Marple’s cup of tea. Yet, there was a darker side to the Golden Age.

American crime fiction has an archaeology that makes sense to me, a twisting double helix of hardboiled and noir that can be traced back to origins in the pages of magazines like Black Mask or The American Mercury, and even to writers like John Fante and Sherwood Anderson, whose unorthodox realism surely influenced James M Cain, Horace McCoy and others.

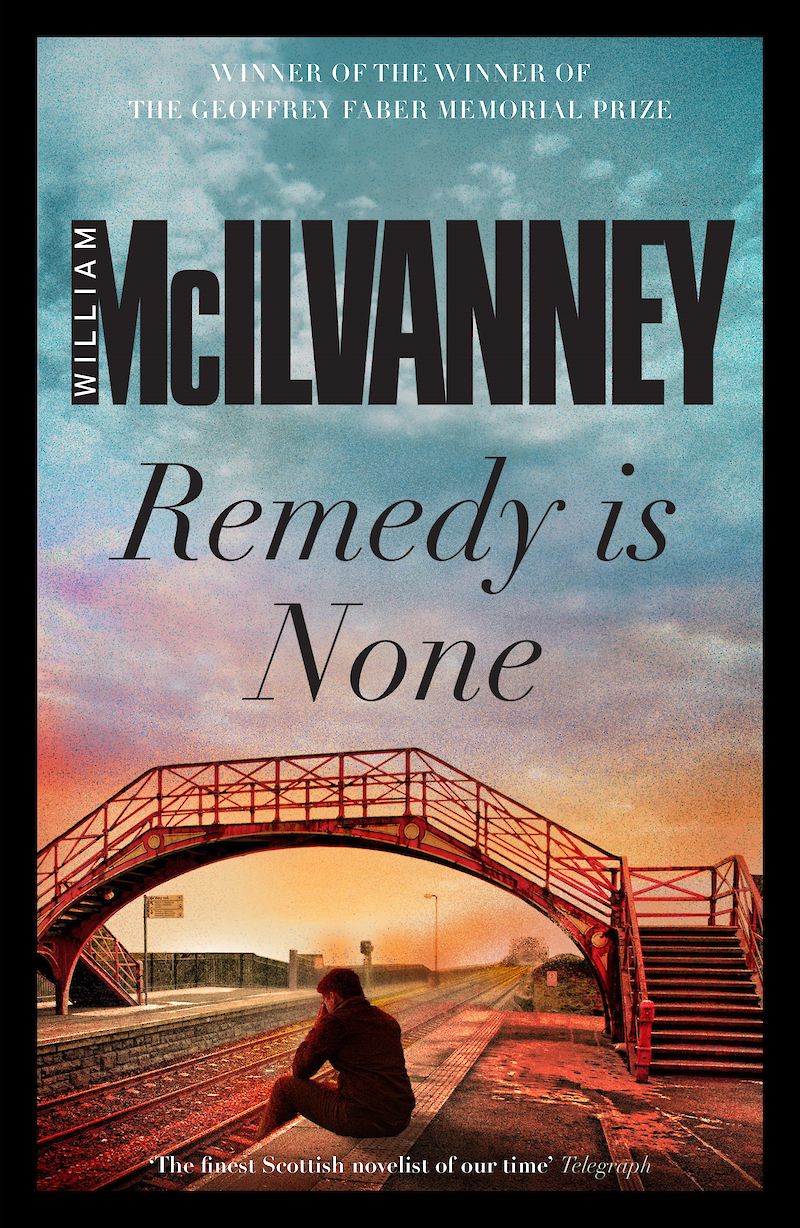

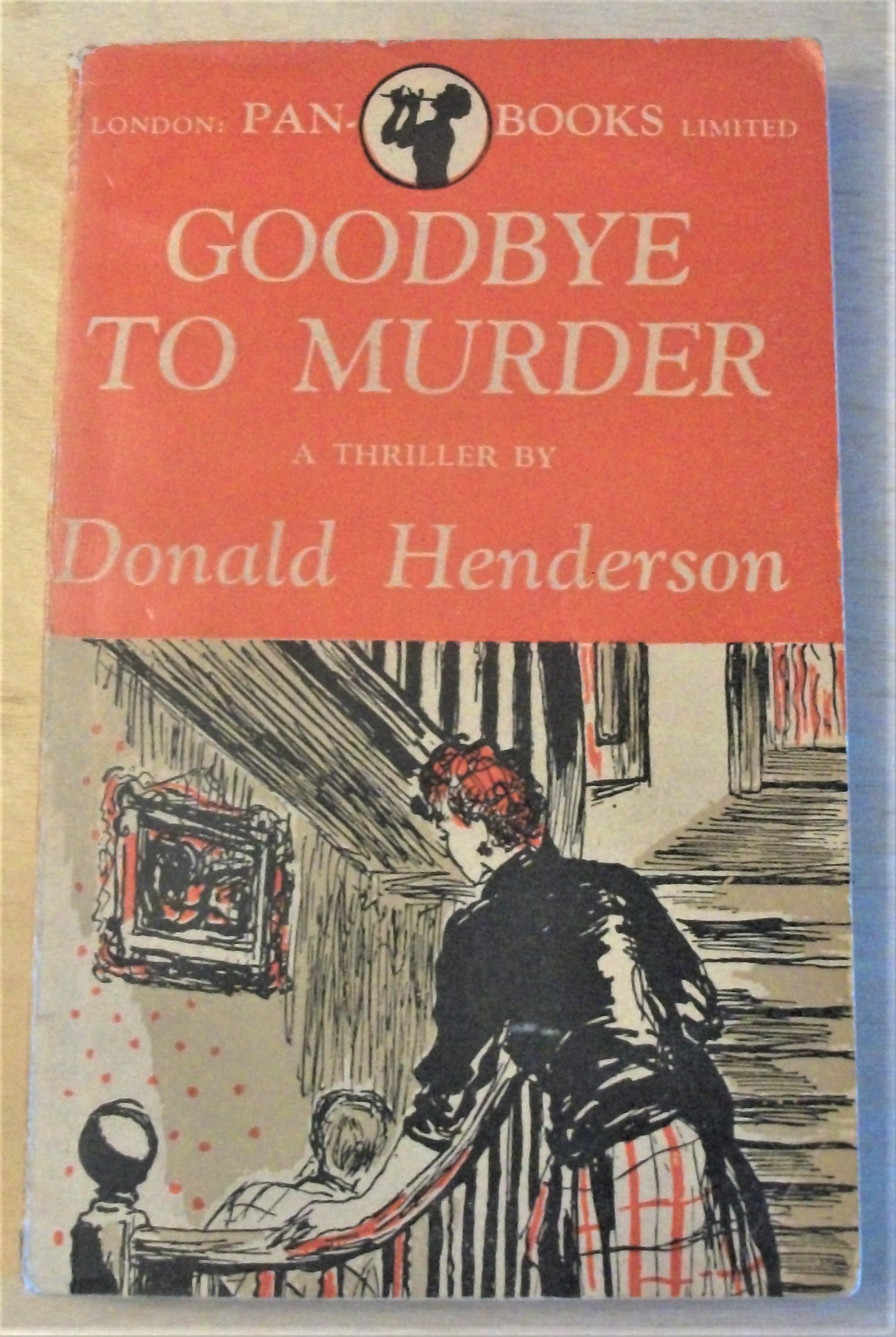

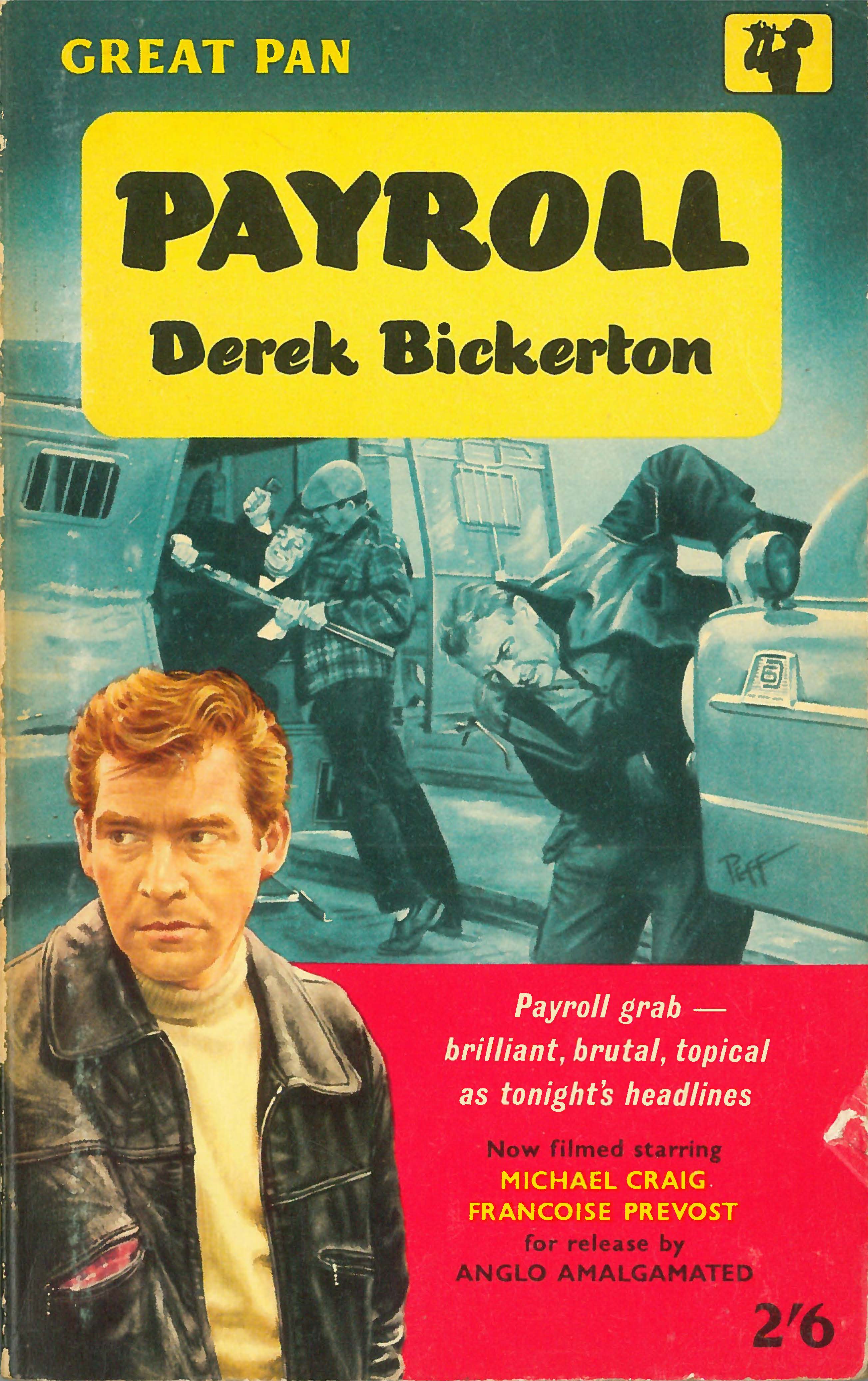

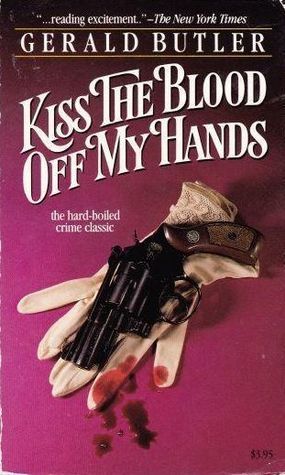

The lineage of British noir, the dark stuff, is less clear. We can go back from Unsworth and Peace, through Derek Raymond and William McIvanney, to James Barlow and Ted Lewis and Laurence Henderson. Before them, there were British crime writers of the fifties who have disappeared from public consciousness, remembered if at all only because films were made of their books, or Corgi and Pan paperbacks survive on the shelves of collectors – Howard Clewes, Donald MacKenzie, Derek Bickerton. Back further, the psychological thrillers of Donald Henderson and hardboiled stories of Gerald Butler of the forties feel like outliers among their Golden Age peers. None of these authors are known anywhere near as well today as the likes of Christie or Allingham or Sayers.

American noir drew heavily on the nation’s experience of the Great Depression – what Sherwood Anderson described as “the breaking down of the moral fiber of American man, through being out of a job, losing that sense of being some part of the moving world of activity…the loss of this essential something in the jobless can never be measured in dollars.” Whilst you might not know it from Golden Age mysteries, Britain did not escape the consequences of the global recession following the Wall Street crash, so where was all of our crime fiction reflecting that?

The crux of the problem lies in how we define crime fiction, or what we consider to be noir – the latter being an especially sticky question, as noir was a retrospective construct. When The Postman Always Rings Twice was published, nobody spoke of such fiction as being noir, and the New York Times review even grappled with the issue of what Cain was: “There is the feeling of realism, of intense realism, in James M Cain’s work, and yet he cannot be compared to such diverse types of realists as Zola, Ibsen, Sandburg, Dreiser, or Hemingway. It is the hardboiled manner…that Dashiell Hammet has stumbled upon.”

So, realism, but at Hammett’s end of the spectrum, rather than Ibsen’s.

The term “noir” didn’t gain much currency with Anglophone critics or audiences until the sixties, with film, and not until the eighties with reference to literature, when Barry Gifford ignited the discourse on American noir with his Black Lizard publishing house, bringing the likes of Goodis, Thompson, and Charles Williams back into print.

We’ve never had that discourse in Britain, never sought out our “Hammett’s end” of realism that might delineate early British noir (and probably never will, because discussing genre now in terms of form or subject matter – how it makes most sense to me – is pointless, as it is largely now a way of categorising books for marketing and sale; what shelves will this book be on, and how will we get it there?).

A book that was particularly important to me was Alexander Baron’s The Lowlife, a slum picaresque about a dog-track player living through the crime, reconstruction, and gentrification of postwar Hackney. It is many things – a lowlife novel, a London novel, a Jewish novel – but nobody would ever file it under crime. Why is that?

From the mid-twenties in Britain emerged writers whose work reflected the social and economic turmoil of the time, set among the boarding houses and seedy hotels of London and Manchester and Paris: Patrick Hamilton (Monday Morning; The Midnight Bell), Jean Rhys (Quartet; After Leaving Mr Mackenzie), Walter Greenwood (Love on the Dole).

In the thirties and forties, what were James Curtis (The Gilt Kid; They Drive by Night), Robert Westerby (Wide Boys Never Work), and Gerald Kersh (Night and the City), if not crime writers? All explored the nexus of crime and poverty, especially where they intersected with gambling. These are all British proto-noir classics, continued by Hamilton (Hangover Square; The Slaves of Solitude) and Rhys (Voyage in the Dark; Good Morning, Midnight) in their ongoing exploration of the low life.

Wartime and the Blitz lent a noirish fatalism to a wide variety of writers: Henry Green (Caught; Back), Elizabeth Bowen (The Heat of the Day), Anna Kavan (I Am Lazarus). Published less than two months after the surrender of Japan, Norman Collins’s London Belongs to Me felt like a bookend to wave off the interwar city, a thunking great seven hundred pages of boarding house bedlam, with conmen and criminals, bombing raids and seances, night clubs and Nazis, and the inevitable spot of killing.

Following that came the postwar grime of Arthur La Bern (It Always Rains on Sunday), Julian Maclaren-Ross (Of Love and Hunger), Alexander Trocchi (Young Adam), and Alexander Baron (Rosie Hogarth; The Lowlife), looping us back to the more established origins of British noir in the sixties.

This is just a sampling, barely a toe dip, but it is clear that in British realism lies the kind of writing that is a truer forebearer of contemporary social crime fiction than the corpsy conundrums of the Golden Age.

Crime isn’t a genre.

It is a church. A marvellously broad church with room for writers of all kinds. Let’s shuffle along and make room for a few more.

White City by Dominic Nolan (Headline, £20)