I was around twelve years old when my mother told me about Ted Bundy. I can’t recall my exact age with certainty—in my memories, I was young, but with a looming sense that I would soon have some growing up to do. So, let’s call it twelve. The knowledge of Bundy—of a man who had killed dozens of girls and women for seemingly no reason, other than he wanted to—was too heavy to hold onto for long.

I was around twelve years old when my mother told me about Ted Bundy. I can’t recall my exact age with certainty—in my memories, I was young, but with a looming sense that I would soon have some growing up to do. So, let’s call it twelve. The knowledge of Bundy—of a man who had killed dozens of girls and women for seemingly no reason, other than he wanted to—was too heavy to hold onto for long.

In the following years, I went through phases of not thinking about serial killers, practically forgetting they existed. Every once in a while, I pulled that knowledge out of the corner of my mind where it had been tucked, and shook it out like an old sweater. I went on long Wikipedia binges, learning about Bundy and others. The cycle went on.

The serial killers who captivated me were the ones who had been known not as local creeps or oddballs, but as seemingly functioning members of society. The ones with jobs and families. The fact that Bundy had been a law student (albeit an unsuccessful one: he never graduated, and his decision to act as his own lawyer, during a criminal trial in Florida, resulted in his execution in 1989) gave him, perhaps, a strange personal resonance in my eyes. My father is a lawyer. As a young adult, I, like Bundy, became a law school dropout, though for different reasons.

We obsess over what we can’t understand. Bundy and those like him represented, in my formative years, the epitome of behavior I couldn’t make sense of. I was—still am—an anxious person, prone to feelings of guilt. One of the defining experiences of my adolescence was my overpowering fear of hurting others, or hurting their feelings. The idea that there were people in the world who not only acted with brazen cruelty, but who kept humongous, life-altering secrets from the people closest to them, was a pit of incomprehension. And so, I kept reading. In time, I transitioned from Wikipedia pages to books, documentaries, and podcasts.

Throughout those years, my father would ask why I found any of this interesting. Those stories were so dark, he said. They were disturbing. Why bother?

He had a point: the men (they were most often men) at the heart of those stories aren’t interesting per se. What’s captivating is the way they interact with the world around them—a world that includes both their victims, and the people those killers are close to. What we’re left to reckon with is what they leave behind: stolen lives, trauma, pain, and, for some, entire existences to rebuild. Those are the pieces that make a compelling serial killer story.

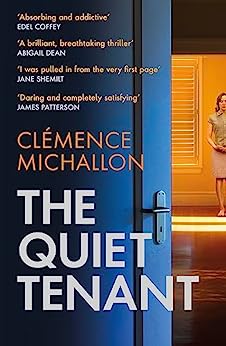

Those aspects came into sharp relief when I started working on The Quiet Tenant. I made a decision early on that in my serial killer novel, the serial killer would not get to speak. Rather, a cast of female characters—a victim he is holding captive, a woman who sees only his perfect facade and has a crush on him, and our killer’s teenage daughter—tell the story. Only by combining their three narratives (and a few additional others) could I capture the narrative in a way that felt truthful. Maybe this is something I inherited from my day job as a journalist: when you want to know the truth about somebody, you don’t (just) ask them. You speak to people who know them, too. You try to get a complete picture of the way they inhabit the world.

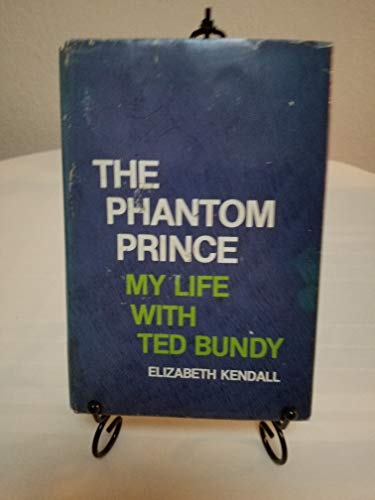

A documentary was fresh in my mind when I started thinking of the story that became The Quiet Tenant: the 2020 Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer. It was based on a memoir written by Bundy’s former partner, Elizabeth Kendall. That memoir, The Phantom Prince: My Life with Ted Bundy, was originally published in 1981, then fell out of print. Before the re-release, I’d visited the book at the New York Public Library, where you could read it on site, but not check it out. When I watched the documentary, I was struck by how successfully it drew the viewers’ focus away from Bundy himself, and asked us instead to look at his victims, and at the people who had shared Bundy’s life.

I didn’t want to lionize the killer in my book, because there is nothing to lionize. I don’t believe in monsters. I believe in people acting cruelly, inflicting pain on others. I believe that a serial killer is like a plane crash: in order to create one, everything that can go wrong must go wrong. From that angle, serial killer stories can serve as parables of human nature, as reflections on cruelty, trauma, and resilience. Maybe it’s ironic that the word “quiet” appears in the title of my novel. Once the female characters in the book started talking to me, I had no choice but to hear them.

The Quiet Tenant

Abacus, Hbk £14.99

20 June, 2023

photographer credit Gabrielle Malewski