Aaron Epstein / Amazon Studios

There are always things you notice for the first time when you re-watch, things your eye is drawn to around the main drives of character and plot. This week I binge-watched the first season of Michael Connelly's superb Bosch, in anticipation of its return for series six. On my second time through, I found myself just as engrossed as I was when it was first shown, impressed by the way the plot strands interact in the overall structure, impressed as always by the acting (and reminded that a couple of key characters had changed—I had forgotten Michelle Hurd played Connie Irving in the first series, and much as I like her and admire her work, Erika Alexander really made the part hers; there was also a character change, as in series one the crime reporter for the LA Times is Adam O'Byrne, playing Nate Tyler: he's aggressive and somewhat old-school and winds up a major part of the story, as you'd expect in a series based on Connelly's work—but in series 3 he's replaced by Eric Ladin as Scott Anderson, who's a bit more like what you might expect a modern reporter to be, interested in deal making, a more modern news man, perhaps. He's perfect for the kind of play and get played business of series 5.

Madison Lintz, Jamie Hector, Amy Aquino, Titus Welliver, Lance Reddick

Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images for SCAD aTVfest 2019

But what I was taken with more in my second spin through series one was the way the scenes are constructed, and specifically the transition and establishing shots. These are standard in any series drama, and frankly, are usually utilitarian: exterior of police HQ, cut to exterior (or interior) of someone's office, depending on whether you want to show the character entering or already seated. Sometimes the camera zooms from the exterior to a window: if you grew up watching hour-long cop shows in the 60s or 70s you know what I mean.

Bosch, however, works with a double-layered approach, which reflects in some ways the greater freedom the time of a self-contained ten episode series provides. Yes, you get the exterior location to interior set. But much of the time this is set up with transition shots which establish neighborhood, background and mood. LA cop shows were always shot in LA light: everything bright, few shadows. Nowadays, in HD, it seems most shows do the same thing, and it would be churlish of me to suggest a paucity of depth in the photography suggests the same in relation to story.

Aaron Epstein / Amazon Studios

Aaron Epstein / Amazon Studios

It is easy to be impressed with the variety of the Los Angeles which Bosch presents: the kind of peeks at the city we remember from movies, especially those that blend together the landscape and architecture. You can go back as far as you want, but it's easy to see influences of many modern films and their views of the city, only here they are mixed as the story moves through more locations than movies can manage. I was struck by similarities opening up behind my eyes. Shots from the other series sprang to mind to, and it seemed an LA panorama: the hard-edges of downtown, as in Heat; noirish shadowy places, everything from Double Indemnity to Devil In A Blue Dress. The series takes us into suburban convenience stores and rural settings only a few miles from the downtown, where Bosch's Angel's Flight harks back to something seemingly now gone. But the point here is that these general shots stand in for specific establishing; they transition us in mood for the scene that is coming up, and when you consider how many directors and directors of photography the series uses, the continuity of purpose is impressive. You might see it in parallel with Connelly's own writing: like the journalist he was he doesn't waste adjectives, he sets scenes primarily by showing what happens in them. Just as 'character is action', as Fitzgerald said, scene-setting is character. This leaves space for the visuals, but the approach of Bosch is very close to Connelly's own: the scene-setting tends to reflect the character and action that will be taking place within it, on the small scale of individual scenes, and, as we shall see, in the bigger picture as well.

It helps that Los Angeles is so engrained in our cinematic memory: Bosch goes to visit Brasher in Venice and Orson Welles' Touch Of Evil springs to mind. Then there are the empty industrial spaces, as in To Live And Die In LA; surprisingly sedate neighborhoods where crime happens behind closed doors, as in LA Confidential, and, as that film reminds us particularly, the way the architecture of the city defines characters as well as scenes: I keep thinking about Bo Catlett's balcony in Get Shorty every time we're at Harry's house.

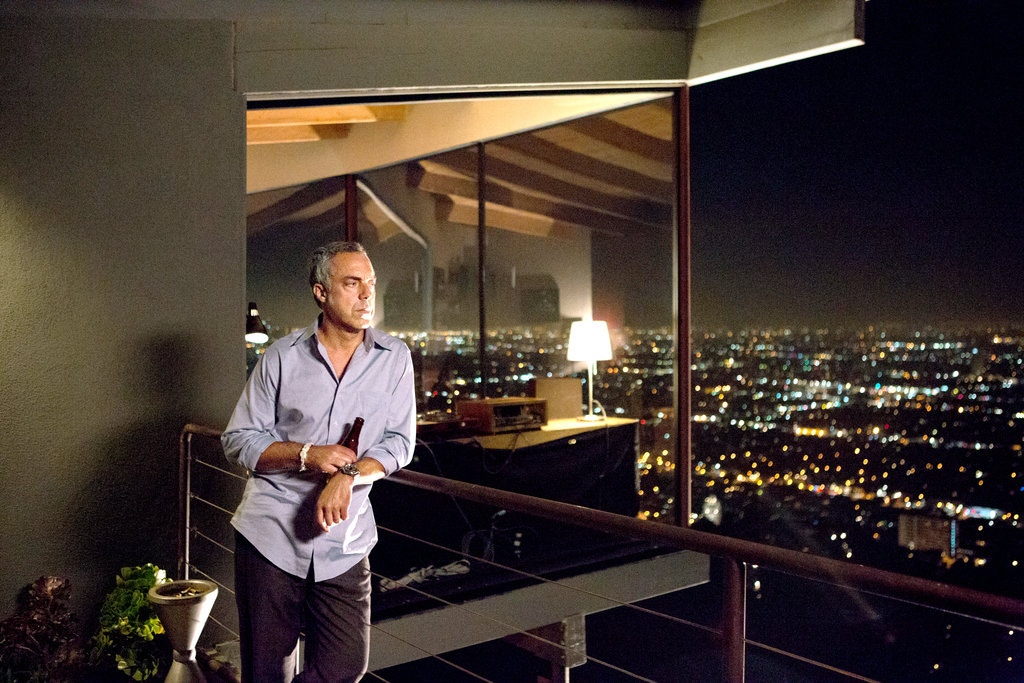

And it's Harry's house in the Hollywood Hills that led me to my second, more important insight into the show. Besides generic establishing shots, and besides the care taken with those transition shots between locations, Bosch offers another sort of view: the wide angle of the whole city, and it is offered with a purpose.

It's not just the view from Harry's balcony, though these are important. Sometimes the view from his window reflects the city below: it sparkles at night, sometimes tempting, sometimes cheering, sometimes dangerous and threatening. These different moods can reflect Harry's own moods, in the same way the jazz on the turntable does. They can also offer a window into other characters: most often Maddie, especially in daytime, when the expanse of the city seems to offer her equal elements of promise and confusion. It's expressionist, with the windows providing the framing and the shifting city showing different moods. But crucially, it's always viewed from above, from the same perspective, and it puts us, the viewers, behind Bosch's eyes, even when Bosch is not the one doing the viewer. In Season 1, Brasher's reaction to the view catches none of this: it's a telling character point, and the angle we see LA from at that point flattens the city out, as if it were a rhinestone curtain. The house is not only Harry Bosch's window on his world, it is our window into Bosch.

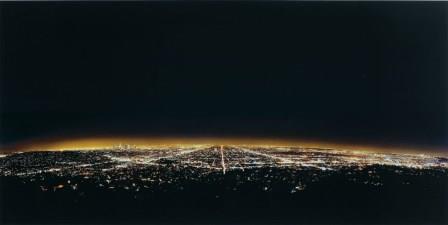

Andreas Gurskey - "Los Angeles"

But just as important, and what I hadn't really caught first time through the series, is the way other panoramic views of LA feature as transitional scenes. These are usually aerials, shot from low angles, but not specifically to link one scene to the next. These cutaways are ways to remind us of the bigger picture, and this is one less expressionist than the artistry of Bosch's windows. This is the big picture LA, and it is remarkable in what perspective we consistently see it. More than anything, it reminded me of a series of Andreas Gursky photographs: the view is elevated, the composition seems flatter than reality, as if to say this is a Los Angeles which itself has less allure, if not depth, than the one you see from Harry's. It is an abstract point of view, in which the city becomes a series a repetitive shapes—in which we no longer have a specific mood, a expression of feeling, set out for us. Rather, we are lost in something which is not so much a maze as an impenetrable surface. We are made smaller by them, disoriented by them, reduced as individuals.

And is that not exactly what Harry Bosch fights against? “Everybody counts, or nobody counts” he says. That is what those grand shots of LA, beautifully shot and judiciously chosen, remind us. They provide a framework for Harry's own personality, the one reflected in his own house; they provide a framework for all the individual places and scenes, characters and actions. It is an abstraction in the way the city is an abstraction, out which we, like Harry, must make sense.