The

drive into town from Cape Town airport focuses on the looming Mountain, the government’s

attempt to hide the sprawling townships and squalid corrugated-iron squatter

camps behind rows of newly built concrete houses and flats pretty much

succeeds. The Southern Suburbs hove into view, then a glimpse of the sea, Table

Mountain - or at least Devil’s Peak – golf courses, suburbia, the University

and lushly forested slopes of the Mountain. Around the corner, the docks and

Waterfront glitter against a dark silver sea, the freeways run smoothly (out of

the rush hour), the CBD is glassy and slick, the meeting of Africa and Europe

complete.

The

tourist experience is dream-like, especially if you leave London in December

and arrive in mid-summer. The light, the air, the space, the beauty, the heat,

the welcome, the amazing value. Most of all, everyone seems happy; races mingle

and seem content; building is rife. Cape Town is a prosperous, beautiful city. As

with any destination however, the reality is just out of shot. Unlike most

other cities, the grim reality threatens to overwhelm paradise.

Friends of ours - a middle-aged couple - who live in a modest but comfortable

neighbourhood, full of cafes and bars, lush gardens and Victorian verandas,

report the drug deals down the street, the unrelenting threat of burglary or

robbery; they tell me that their fervent wish is, when the time comes, they are

robbed by the ex-military professionals who might pistol-whip them, but leave

them unharmed. The desperate, drug-addled, knife-wielding and gun-toting are

truly terrifying. For them, dogs are pets, but they are also guards and another

layer of alarm. They are usually left at home to fulfill their role when owners

go away, be it to work, for the weekend, or even an extended holiday.

When my wallet was lifted at the airport a few years back (the only instance of personal crime I’ve experienced), my parents in the UK received a call from a man who had retrieved it. We travelled to Khayelitsha, a major township on the Cape Flats, maybe twenty miles from the central Cape Town. A black African man, living with his wife and baby in a clean concrete house of three rooms. He was a teacher, ashamed there was nowhere to sit down; he had not been paid in

eighteen months. Despite clearly struggling, we were offered tea and biscuits.

He refused reimbursement for the long-distance telephone call. If the ANC have

one responsibility, it to education, to give everyone a chance. There are many

who feel that this promise, amongst so many others, will not be fulfilled.

A

few days later, I visited Langer – an older township, closer still to town –

for a cricket match. My friend was their star cricketer, the only white face in

the match. We were given the best seats – wooden barrels – offered food and

beer. The Langer team loved being a mixed team. When we returned to the

captain’s house, it was one small room, concrete again, but unheated or cooled.

At night, he told us, noise would keep him awake: from the freeway, the

shebeen, the ghetto blasters. His house had been broken into over fifty times.

But, he loved Langer. He was twenty-eight. I had guessed, thankfully not out loud, that he was forty-five.

My

police advisor, now a Captain in the SAPS, has been posted to Philippi, a

township of a quarter of a million. She is one of the best shots in the SAPS,

but even she is afraid. When she reaches the outskirts of the township each

morning, she must ring through to the station. A security patrol is dispatched

to escort her to and from work. Here, men kill because you spill their beer,

look at their girl, or smile at wrong moment. Almost everyone who operates in

Philippi has a connection to drugs or firearms or excessive alcohol – and that

is just the police.

In

the centre of Cape Town and The Waterfront, tourists are as safe as in any

major city. The Cape Town authorities have clamped down on begging,

pick-pockets and thieves. You can enjoy wonderful bars, clubs, cafes and restaurants,

galleries and markets, relaxed in the knowledge that Cape Town is safe. You

won’t see many black people – other than serving you – and after a day or two,

it’s easy to feel that Cape Town is a city of white people, waited on by the

black and coloured population.

The sadness is that the disconnect grows as the economic gulfs widens. A few black and coloured citizens can now be seen in white Rolls Royces and matt-black Range Rovers but, for the most part, it is the white Capetonians who install

ever more advanced alarms, pay more for private security and surround

themselves with cameras and razor-wire. They drive, windows sealed ignoring

everyone.

We

live in a small house without bars or an alarm. Admittedly we have nothing of

any value thieves might target – no TV, no computers, no object d’arts. Our

house is full of branches and rocks from the Mountain, sculptures, drawings and

heavy second-hand furniture. We drive with our windows open and we chat to the

hawkers – almost all men from every country in Southern Africa - who appear inever

greater numbers at every junction. We notice that the universities are full of

black and coloured students, that school-children walk in neat lines to more

and more places of education, that non-white businesses are starting all over

town.

No

specific legislation will brook the divide. Everyone feels hard done-by now, the

black and coloured ghettos get bigger, the working class whites have fallen

below the poverty line. Capetonians feel pessimistic. But, Cape Town possesses

magic qualities. If everyone is patient and reasonable; if the extremes of

opinion can remain muted, there is anticipation at the tip of Africa that, as

has been so long hoped for, it can become a beacon at the bottom of a giant and

troubled continent.

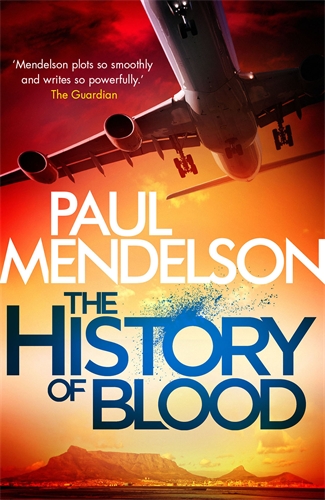

About the Book ...

When the South African Police Service receive a panicked call for help from the wayward daughter of a former Apartheid-era politician, they discover not only her body but, within it, a message which will take Colonel Vaughn de Vries and Don February of the Special Crimes Unit on a journey through their country – and their country’s past – to decipher and resolve.

When the South African Police Service receive a panicked call for help from the wayward daughter of a former Apartheid-era politician, they discover not only her body but, within it, a message which will take Colonel Vaughn de Vries and Don February of the Special Crimes Unit on a journey through their country – and their country’s past – to decipher and resolve.

As organised crime grips South Africa, new players arrive in Cape Town, determined to exploit the poor and hopeless, promising redemption. While other government agencies snap impotently at the small fish, De Vries, linked by a personal connection, resolves to follow this trail to its source and take it down from the top. As decades old webs of corruption and influence are exposed, and the boundaries of morality blur, his decisions begin to impact on his friends, colleagues and family.

Constable (7 July 2016) £7.99 pbk

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.co.uk