Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip. Sears lives in Johannesburg, South Africa, and Trollip divides his time between Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Knysna, South Africa.

During the 1980s, we would rent a small airplane in

Johannesburg and fill it with friends, wine, and food – in that order.

After take-off, we would head for Zimbabwe or Botswana to view and

photograph wildlife and birds – and to savour South African wines around a

hardwood camp fire.

In the early evening on one trip to the Savuti plains

of the stunning Chobe National Park in Botswana, we witnessed lions stalking

and killing a wildebeest. Right behind was a pack of hyenas, harassing the

lions to get to the carcass. Sometimes one hyena would bite a lion’s

tail. When the lion angrily turned on it, another hyena would dart in and

steal some of the flesh. By morning there was nothing left of the

wildebeest except its horns. The hyenas had finished everything off, including

the bones.

That night, over a glass or two of wine, we decided

that if we were ever to commit murder, the best way to get rid of the body

would be to leave it for the hyenas. No body, no case. And that

suggested an intriguing premise for a crime novel.

The idea languished until 2003, when we decided we

should do something more than just think about it. A month later, Stanley

remembers receiving a draft of the first chapter from Michael. In it our

perfect murder became imperfect as a game ranger and a professor stumbled upon

a corpse, just before a hyena finished devouring it. So there was a body,

and there was a case. Stanley liked the chapter and asked Michael what

happened next. Michael didn’t know.

Thus started a long-distance collaboration between us

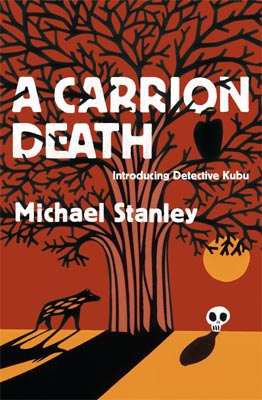

that resulted in the publication in April 2008 of A Carrion Death in the

United States (HarperCollins) and the UK (Headline). Stanley had just

retired from an academic career in educational computing in Minneapolis,

Minnesota, and Michael, a mathematician, was managing a science division for a

large mining house in Johannesburg. Using email and VOIP (voice over

internet protocol) in the form of Skype, we hammered out the outline of a novel

and started writing.

Neither of us had written fiction before, so there was

much to learn about how it differed from academic writing. Nor had we

written together, so we had to learn where each other’s strengths lay, how to

harness each other’s creative side, and how to differ civilly. But we

were long-time friends, and our main goal was to have fun developing an idea we

had concocted almost twenty years before.

And what an adventure it was. Believing in the

age-old advice that one should write about things one knows, we decided that

the professor, who was one of the two people to discover the body in the

desert, should be the book’s protagonist. Both of us having been

professors, we liked the idea of a smart professor solving a mysterious murder

in the Kalahari! It quickly became obvious to us, however, that the

police would have to be involved. So in Chapter Two, an Assistant

Superintendent in the Criminal Investigation Department of the Botswana Police,

David Bengu by name, jumped into his Land Rover in Gaborone and set off to

investigate.

By the time he arrived at the scene of the murder,

Bengu, nicknamed ‘Kubu’ – Setswana for hippopotamus for his considerable bulk –

had taken over as the protagonist. We were astonished how this supposedly

second-string character took over and elbowed himself into the number one

position. We were obviously naïve, because we had thought that writers

controlled their characters rather than the other way around.

Kubu continued to evolve throughout the book, ending

up as an appealing character, who loves his wife, his food, and his wine.

He is normally placid with a keen brain and sly sense of humour but, like his

animal namesake, he can be formidable and dangerous. Kubu is a policeman

one does not want to cross.

From the outset, we wanted to write more than a murder

mystery. We wanted readers to learn something about the sights, sounds,

and cultures of Botswana. We wanted them to smell the desert and imagine

the spectacular sunsets over the Kalahari. We were committed to depict

this remarkable country as authentically as possible.

So we continued to visit Botswana regularly to verify

the factual aspects of the book, as well as to ensure that the fictional

aspects made sense in today’s environment. In all of this we were blessed

with good luck. For example, after we had repeatedly tried to make an

appointment, the then director of the Botswana Criminal Investigation

Department (CID) eventually told us that we had worn him down, and that he

would spend an hour with us. In the end he spent a whole Saturday

afternoon showing us around. And what an afternoon it was. We

learned about the Botswana police and a number of famous cases. He showed

us the Police Training School that he had been instrumental in

establishing. He gave us information about the workings of the CID and

the relationship of the Botswana police with their counterparts in South Africa

and Scotland Yard. And while we were touring Gaborone, he deflected

repeated phone calls from a subordinate who wanted the Director’s advice on

handling a gang the police had just arrested, who were armed to the teeth with

AK47s. The Director brushed the phone calls off with an abrupt ‘I can’t

talk now. I’m busy showing some people around’.

The first question we are usually asked is how we can

write a novel together. In contrast to conventional wisdom, we have found

collaborating on a work of fiction to be a wonderful experience. We

brainstorm nearly every day, even though we are thousands of miles apart, and

hammer out the next few scenes of the book. One of us writes the first

draft and emails it to the other – an eager reader. A few hours later the

draft is returned with edits and comments. We then go over the edits one

by one, eventually deciding how best to word the particular passage. Each

passage bounces back and forth several times and so is eventually written not

by one of us, but by Michael Stanley.

Most commentators on A Carrion Death mention

Alexander McCall Smith’s Botswana series featuring Precious Ramotswe.

Although A Carrion Death deals with death, murder, and corporate

shenanigans, which Precious would find abhorrent, it shares with McCall Smith’s

books a love of this part of Africa, the dignity of its people, their

friendliness, and their respect for friends and family.

We have been delighted by the

positive reception Detective Kubu has received. He will re-appear in our

second book, A Deadly Trade, which Headline will release in April

2009. Unlike A Carrion Death, which is set in the arid Kalahari

Desert, A Deadly Trade is set in the lush riverine forests of the

Linyanti River in northern Botswana. The back story is about how the

Rhodesian Bush War forged strange relationships, both good and evil. The

story itself, set in present day Botswana, is about the dissolution of two such

bonds.

A CARRION DEATH is available in paperback £7.99 Headline Publishers, October 2008

why wife cheated

read online affair

reasons why women cheat on their husbands

open what to do when husband cheats

wife adult stories

open adult stories choose your own adventure

cheats

site why women cheat in relationships

manufacturer coupons for prescription drugs

site cialis coupons and discounts

cialis coupons online

read prescription savings cards

allotment

click allo allo

prescription drugs discount cards

go discount drug coupons

naltrexone studies

naltrexone 4.5 low dose naltrexone contraindications