When I announced last year that I was ending my Getting Away With Murder column after two hundred editions and retiring from front-line reviewing, the world of crime fiction breathed a sigh of relief. When I said I had plans for a series of features reviving some forgotten favourites, one regular reader commented ‘So, just old stuff then?’ Well, my young friend, you hit the nail on the head with an anvil there and I make absolutely no apology for that.

In fact, after reviewing nearly 3,000 crime novels over 34 years, I decided it really was time to tackle the To-Be-Read pile, now resembling three Leaning Towers of Pisa, which I have accumulated but never had time to do justice. I was partially inspired by an American chum who, on reaching the age of eighty-six with a massive TBR pile, chose just enough books to keep him going until he reached the age of one hundred, and then sold the rest of his collection. Sadly he never made his goal, but he inspired me to make the demolition of my To-Be-Read pile a lead item on my personal bucket list.

So, in no particular order, I will share some of the joys and disappointments of rediscovering books I should have read many years ago had I not been distracted by those pesky new crime writers. And as that reader who said “Just old stuff, then?” has subsequently contacted me saying how much he missed Getting Away With Murder, this ‘Revival’ will be done in traditional GAWM style; i.e. rambling and occasionally accurate.

From the TBR pile

I have not read much by Australian novelist Morris West [1916 -1999], though my mother was a big fan, especially of his best-known novel The Shoes of the Fisherman, one of the books which gained him the epithet ‘the Pope of the Vatican thriller’. Certainly he seemed to corner the market in ‘religious thrillers’ - unsurprising given his early experiences as a Christian Brother, although he left before taking his final vows as a monk in 1939 to serve in the Australian army, being commissioned as a lieutenant in Military Intelligence. After a post-war career producing radio plays, he moved to Sorrento in Italy with his second wife and began to write novels with increasing success. The Big Story is a cracking little thriller about an American journalist who thinks he has proof of the corruption of an aristocratic Italian politician but comes under pressure – from a variety of sources – to bury his big exclusive. Pitted against the rigid Naples class system and macho Italian concepts of ‘honour’, the journalist would seem to have little option, especially when he is framed for the murder of his informant and effectively becomes a prisoner in the home of the politician he aims to bring down.

It was filmed as The Crooked Road in 1965 starring Robert Ryan, with the action transferred from Naples to the Balkans.

Overload (1959) by Desmond Cory was originally published as Johnny Goes South, as the eighth outing for Irish-Spanish secret agent Johnny Fedora created by Shaun Lloyd McCarthy [1928-2001], who, thanks to his debut pre-dating Casino Royale by two years, has a claim to being the first ‘licensed to kill’ agent to work for the British secret service.

Described by critic Anthony Boucher as ‘the thinking man’s James Bond’, Fedora shared all Bond’s toughness and hedonism but also had a cultured side, notably as a more-than proficient pianist, as was his creator. Fedora’s early career involved hunting down Nazi war criminals and ended, in the 1960s, with what became known as the ‘Feramontov Quintet’ and chronicled Fedora’s duel with his KGB nemesis. In between Fedora was sent on missions to all four points of the compass, quite literally, and this one finds him in South America where he is caught up in the politics of an insurgent break-away state demanding independence from Argentina. Fedora spends most of the book explaining (and practising) systems of interrogation to the putative regime’s dubious leaders and this I found to be the most disappointing of Fedora’s adventures.

I’m not quite sure how I missed reading Gavin Lyall’s The Conduct of Major Maxim back when it was published in 1982, but discovering it after all these years was an absolute treat.

I had always been a fan of Gavin’s early thrillers from the 1960s – and told him so in cringeworthy gushing terms when I first met him. The creation of Major Harry Maxim marked Gavin’s move from adventure thrillers (usually involving aeroplanes) into spy fiction and although the plot is seeded on the borders of East and West Germany, much of the action, of which there is plenty, takes place in London’s docklands and, unusually, in the East Yorkshire port of Goole.

In spy stories, dramatic finales usually take place in exotic locations – on board nuclear submarines at the North Pole, in poisonous Japanese gardens, on ski slopes in Alps, on (or under) the Berlin Wall, etc. etc.– but The Conduct of Major Maxim shows that a good writer can produce tension and excitement on the unpromising Goole dockside.

The same cannot really be said for Spies Have No Friends which has its dramatic set pieces in the wintry Irish Sea off Birkenhead and, in a slightly ridiculous car chase, along the Mersey Tunnel on Christmas Eve.

Spies Have No Friends (1963) was the fourth of half-a-dozen spy thrillers written by the prolific Harry Hossent (1916-1989) to feature special agent Max Heald, who the Evening Standard ‘must be James Bond’s first cousin’ (Hmm, possibly a very distant cousin...). Heald made his debut in 1958 in Spies Die At Dawn, a convincing, low-key spy story involving Russian moles very close to home, but subsequent adventures, such as this one, failed to live up to that initial promise, although the books did enjoy success in translation in France and Italy.

I was always a great fan of the books of John Gardner (1926-2007) and the characters he created, from Boysie Oakes to Herbie Kruger to Suzie Mountford, and even had the honour to re-publish his 1964 comic masterpiece The Liquidator as a Top Notch Thriller. But I was never particularly attracted to his James Bond continuations.

Although Gardner himself said that The Man From Barbarossa (1991) was his personal favourite, I have to admit that it did nothing for me, either thirty-odd years ago or attempting to re-read it now. In fact on both occasions I never finished it, which is painful to admit. I certainly read his first Bond book, Licence Renewed, when it came out in 1981 and I fondly remember the story H.R.F. (Harry) Keating told me about its genesis.

As crime fiction critic for The Times, Harry had been approached by the estate of Ian Fleming to help find a suitable author to re-start the Bond stories in novels. Harry thought of Gardner, then living in Ireland, and wrote him a letter ‘in pen, on Basildon Bond paper’ (Harry was a letter-writer of legend and had amassed a considerable supply of Basildon Bond notepaper). Gardner, whose first novel was very much a spoof ‘anti-Bond’ spy story, already a prolific and successful thriller writer, could not resist and I believe he ended up writing more Bond books than Ian Fleming.

I have been devouring the backlist of Joseph Kanon, the American master of historical spy fiction, having read three on the trot, the latest being Leaving Berlin from 2014.

Set in Berlin (who’d have thought it?) in 1949 at the time of the famous ‘air bridge’ flying supplies into the isolated West Berlin, this is a convoluted spy story involving the ‘re-defection’ (if that’s a word) of a German-Jewish American writer persecuted by the McCarthy witch-hunts who flees to East Berlin to seek sanctuary. He is, of course, secretly working for the fledgling CIA but is distracted from his mission by old family loyalties.

There are some standard Kanon plot traits, familiar from his other books: the early murder implicating the main characters, someone who has to hide from the secret police and then be helped to escape the city. Much of the story being told in long sections of dialogue, usually conversations at cocktail parties or official receptions where no one says what they mean, except perhaps, in this case, Berthold Brecht!

Kanon’s style and pacing may not be to everyone’s taste, but he is a fine writer with a terrific sense of historical place. His post-war Berlin is authentically grim and gritty and in Istanbul Passage (2012) he nails the old Ottoman city as well as Eric Ambler.

Confession time. I had only read one Tim Sebastian novel before I met the former BBC foreign correspondent – once expelled from the Soviet Union and accused of being a British spy (falsely, he says) – for lunch. He turned out to be such an engaging, erudite and charming guy that I loaded my TBR pile with several of his thrillers.

War Dance (1995) is an exceptional thriller, a fast-moving story of international political chicanery, deception and betrayal, the setting being the highly inflammable Balkans (again!) and the British army unit sent as UN peacekeepers caught in the middle of an increasingly violent situation. Colonel Tom Blake, a superbly professional soldier who inspires devoted loyalty from his men (if not his wife), finds himself set up, betrayed and finally a target. Fortunately, Tom Blake is not one to take the UN mandate of ‘don’t shoot unless shot at’ too literally.

I am continuing to work my way through Tim Sebastian’s back list with great pleasure and cannot really understand why he is not far better known in the pantheon of spy-writers.

Whilst still staggering from the experience of watching the film The Zone of Interest, I was drawn to Commandant of Auschwitz, the confession made whilst in the hangman’s waiting room by Rudolf Hoess, first published in English in 1959, a book I had not read since university days.

Like the film, the book is horribly and utterly chilling; an exemplar of what Hannah Arendt called ‘the banality of evil’. It is not light reading, but it is necessary reading for anyone who does not think such grotesque crimes could possibly happen in such a matter-of-fact way.

I have not read much science fiction, having been too often drawn in by fantastic set-ups and scenarios (planets run by apes, time-travel, the ingredients of soylent green and so on) and then disappointed as a plot thins or disappears entirely.

Several friends aware of my condition have, over the years, recommended The Man in the High Castle where the set-up could not be more intriguing. Having lost WWII, the United States is occupied in the east by the Nazis and the west coast becomes a vassal state of Japan with, by 1960, a neutral zone between them. With power struggles in Berlin likely to lead to a war between the former Axis partners, various characters, American and Japanese, try to make sense of this crazy world using I Ching hexagrams and a dangerously subversive novel The Grasshopper Lies Heavy written by the man in the high castle himself (though the high castle itself is a fiction).

On second reading (after four failed attempts), I can’t say I am any clearer about where TMITHC was trying to take me and, frankly, found some of the dialogue in ‘Japanese English’ it to be rather off-putting. Still, it had its moments, particularly the enjoyment by several characters of marijuana cigarettes manufactured under the brand name Land O’ Smiles.

An Official Apology

I have long had an unhappy relationship with the detective stories of Nicholas Blake (Cecil Day-Lewis, 1904-1972) and particularly with his Minute for Murder from 1947.

Set at the end of WWII, this murder mystery features a leading British spy, one of the heroes of the Special Operations Executive, a much decorated officer whose success at infiltrating the highest levels of the Nazi elite seems to have due mostly to his skill as a female impersonator. So pleased with his track record of fooling men, the officer thinks nothing of dressing as a woman in order to visit his girlfriend on his return to London ‘as a lark’. She, of course, is shocked (perhaps the hat was a mistake...or the moustache...) though no one else in the book seems at all troubled.

I have to admit I was slightly scathing when I wrote about Minute For Murder for a distinguished crime fiction quarterly, but I discover, on reading Ben MacIntyre’s superb history of Operation Mincemeat, that I might have to eat humble pie.

It seems that British Intelligence’s head of deception operations in the Mediterranean (to fool the Germans into thinking the Allies would invade Greece rather than Sicily) was a certain Lt-Colonel Dudley Wrangel Clarke, who took his talents to deceive to extraordinary lengths by dressing as a woman. While thus ‘under cover’ in Madrid during the war, he was arrested by Spanish police (quite why is not clear) and photographed. Enough diplomatic and intelligence network strings were pulled in order to get his release. Much lauded for his military service and intelligence work (he was instrumental in the formation of the Commandos and the SAS), Dudley Clarke (1899-1974) wrote numerous military histories after the war and one thriller, Golden Arrow, in 1955, which is said to be pretty good on female fashion.

In Other News

Now freed from the tyranny of having to review a regular tsunami of new crime fiction I have the luxury of picking and choosing titles I genuinely like. Most publishers have already totally forgotten me, but I am delighted that I am still remembered by someone at Hodder & Stoughton and thank them for advance copy of Leo, the new novel to be published in October by Deon Meyer which features my favourite pair of South African detectives: Benny Griessel and Vaughn Cupido.

Not only is Deon Meyer one of the best crime writers in the world (let alone South Africa), he is also an absolute diamond geezer.

Back in 2018 I edited a Top Notch Thriller edition of Peter Driscoll’s spy thriller The Wilby Conspiracy which, when first published in 1973, was lavishly praised by both Eric Ambler and Len Deighton. As much of the action in the book, set in South Africa, involves a long chase across country and a region called the High Karoo, I wondered where I could get a suitable photograph for the cover. If only I knew someone who knew the country and had a motor-bike and was and was an accomplished photographer...

Fortunately I did and Deon generously did the honours and received (as far as I know) his first credit for cover design.

Bodies in the Bookshop

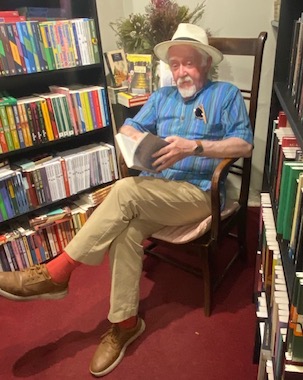

Despite several false starts, I eventually made it over to Richard Reynolds’ new emporium, Bodies in the Bookshop (new and second-hand crime fiction: the clue is in the title) in Cambridge where I was able to take part in the age-old tradition (well, it’s been going a couple of months) of visiting authors sitting in “Bunty’s chair” to sign copies of their books.

Nothing has been negotiated and no money has changed hands (yet) but I do hope that Richard’s new venture will stock or even take advance orders (and yes, this is a hint) for my new novel Mr Campion’s Christmas which is published on 5th November and which has already received a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly in America.

It will be my twelfth Campion ‘continuation’ and my last.

All Is Revealed

For years I have been under the impression that the initials CWA had something to do with crime writing. However, the scales have fallen from my eyes because I now know it stands for the Cat Writers Association based, I believe, in Texas.

As this club is quite likely to have me as a member, I have taken steps to join by submitting a testimonial from one of the many feral cats which stalk the grounds of Ripster Hall.

And now back in to retirement.

(For now)

The Ripster.