|

RIPSTER REVIVALS #8

An occasional series featuring authors and books which may have been unjustly forgotten, ignored or discarded.

|

Why have I not read William McGivern until now? I blame Maxim Jakubowski.

In the good old early days of Maxim’s Murder One bookshop, he introduced me to a clutch of American hard-boiled authors, among them: James Crumley, James Ellroy, Charles Willeford, David Goodis and Charles Williams. But he never mentioned William P. McGivern, even though he had recently edited a new edition of McGivern’s best-known story The Big Heat for Simon & Schuster’s Blue Murder imprint.

It took me, disgracefully, thirty-five years to discover him and I did so in the most unlikely circumstances. In a second-hand bookshop in the heart of Rome earlier this year, I spotted a 1959 Fontana paperback in pristine condition for three Euros and simply couldn’t resist. It was The Seven File by William McGivern. I had never come across that (rather oblique) title before but I was aware that a McGivern book had been the source for the famous film noir, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, which became notorious for the scene where Lee Marvin throws a pot of scalding coffee into the face of Gloria Graham. (The scene is in the book.)

I found The Seven File – the title refers to an FBI code for a kidnapping case – totally gripping as a gang of ruthless hoodlums plan and carry out the kidnapping of a baby from the home of a well-off New York family. the gang are a particularly nasty bunch and destined to eventually fall out but for a while seem to be getting away with it. The kidnapped child’s family has, however, called in the FBI who, acting almost undercover, begin to track the kidnappers.

McGivern maintains the suspense throughout and there is a particularly chilling scene where the ‘bagman’ employed to collect the ransom money cannot resist tormenting the mother of the kidnapped baby and actually visits her in order to enjoy her pain and distress almost as an emotional vampire. It would have made a great film noir and indeed several of McGivern’s books were filmed, including Rogue Cop, The Caper of the Golden Bulls and Night of the Juggler.

Although not his first novel, The Big Heat (1953) put him firmly on the crime-writing map with a hard-boiled tale of one uncorruptible cop taking on a city administration riddled with graft and corruption. It was quickly filmed starring Glen Ford, Gloria Graham and Jocelyn Brando (Marlon’s sister) and film won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America, of which McGivern was later to be made president.

It was rapidly followed by Rogue Cop (1954) which was also filmed, starring Robert Taylor, in another story about corruption among policemen, something McGivern seemed to have a fatalistic, almost pragmatic, view of. This time the protagonist is a corrupt cop in another corrupt city, one of many cops who use their badges ‘as collection plates’ for the gangsters running thing. His problem is that his brother, the honest cop in the family, is about to identify one mobster who is prepared to squeal on the others and is therefore being pressurised to change his testimony – the pressure to be exerted by his own brother.

It seemed that McGivern was cornering the market in hard-boiled police stories which pulled no punches, but he had only just begun to extend his range.

*

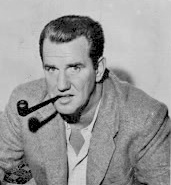

William Peter McGivern (1918-1982) was born in Chicago and served as a sergeant in the US Army during WWII, being decorated following action during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. After the war he studied at Birmingham University in England before returning to America to work as a police reporter on the Philadelphia Bulletin. He married journalist and author Maureen Daly in 1947 (they were to co-author memoirs of their travels in Ireland, Kenya and Spain) and published his first thriller in 1948. Clearly influenced by his time as a police reporter, McGivern hit his stride as a full time author in the 1950s and in total produced 23 mysteries as well as short stories and other fiction. In the early 1960s, he was lured to Los Angeles to write for television (including episodes of Ben Casey, The Virginian and Kojak) and films, scripting the Dean Martin ‘Matt Helm’ comedy The Wrecking Crew (later to be immortalized in Tarantino’s Once Upon Time In Hollywood) and the John Wayne cop vehicle Brannigan, which featured Wayne in a saloon bar fight in a London pub alongside Richard Attenborough!

After devouring The Seven File, I was hooked and thanks to my bespoke book dealer, I managed to track down a clutch of other McGivern titles which had passed me by.

All proved addictively readable and none disappointed and I was not put off by discovering that the review of McGivern’s Odds Against Tomorrow in The Guardian in November 1958, written by ‘Francis Iles’ no less, said it was ‘competent as ever but too harrowing for this reviewer’s taste’. I had never thought the author of Malice Aforethought to be such a wimp and I continue to search for a (reasonable priced) copy.

In the meantime, my thoughts on the McGivern’s I have feasted on in the past three months...

Margin of Terror (1955): McGivern drifts – possibly for the first time? - into the field of spy-fiction. An Ambler-esque character, an American engineer Mark Rayburn (not to be confused with Malcolm Gair’s series private eye Mark Raeburn) with a Good Samaritan complex, spots a girl in need of help in a hotel bar in Rome on his last night at the end of a two-year contract working in Europe. Almost immediately he finds himself up against a ruthless KGB hit squad determined to smuggle a kidnapped left-wing American political agitator back to Russia for preaching against the ruling party. After much skullduggery in and around Rome (and with some dubious geography), Rayburn comes through to ease the damsel’s distress. Good spy trade craft and some fascinating insights into American communists living in exile.

The Darkest Hour (1956) features another badly-done-by cop, this time one framed for murder but out and seeking revenge after (only?) five years inside. The nub of the action revolves around the New York docks and the inherent corruption of the union ‘locals’ running things there. Our honest cop, having lost his job, his reputation and his wife, knows who the bad guys are but cannot prove it. If he stirs things up enough though, the villains might just complete his revenge quest for him.

A Choice of Assassins (1964) could be McGivern’s bleakest, most noirish thriller. Set in southern Spain near Torremolinos (before Monty Python made it infamous), the book revolves around a destitute American news photographer descending into alcoholism after the death of his wife – and the early chapters detailing Tony Malcolm’s craving for alcoholic oblivion are both powerful and disturbing. Falling in with local gang of thieves, Malcolm is reprieved from a game of Russian Roulette on condition that he “owes” the gang a killing. The rest of the novel is devoted to Malcolm’s attempts to sabotage the gang’s activity whilst seemingly determined to sabotage himself, despite a rapid (and painless) sobering up. The collateral damage involves two murders and a very tragic suicide (and the female characters come off very badly). The outcome is predictable in terms of plot, but the ending of the story is somehow unsatisfactory, it being unclear as to whether Malcolm has redeemed himself – or whether he’d even tried to. But still, it’s a powerful piece of writing.

Caprifoil (1972) sees McGivern clearly opting for spy-fiction, though the old maxim that power corrupts is still an underlying theme. A quartet of agents now seemingly retired from working ‘off the books’ for the CIA in Europe are reactivated when one of them sends out a coded message asking for help and then disappears. One of the group is found dead in Paris, leaving the other two to follow a trail of dubious leads whilst avoiding the attention of the CIA and a hit-squad of assassins out to stop them. The plot expands to involve the White House, the President of France and a stand-off in Algeria with an unlikely pan-Arab militant organisation called the Saracen Vector whose ultimate aim is the destruction of Israel using nuclear bombs provided by the USA! If the ‘international conspiracy’ third act of the book is somewhat disjointed (and pales in the light of real events in the Middle East and North Africa), the initial set-up is a first-rate spy story with two very resourceful agents , one American, one British, who may have opted for a quieter life but have not forgotten a shred of spook tradecraft.

Reprisal (1973) is a stone-cold revenge thriller, with three fathers, whose children have died in a mutual drug overdose, band together to dispense violent justice on the drug dealers they hold responsible. This is a superb novel, with some unlikely, and flawed, heroes one of whom is a Hollywood producer who has green-lit a spy film because “there were still creative changes to be rung on the James Bond-Matt Helm outrageries ...” – which was, of course, no reflection on the scriptwriter of that Matt Helm ‘outrage’: William P. McGivern!

And yet, in the middle of my McGivern reading binge, the book which gripped me most was not one of his hard-boiled mysteries, or his spy novels, or any of his fantasy/sci-fi stories (with which I am unfamiliar), but rather his clearly biographical novel Soldiers of ’44 (1979).

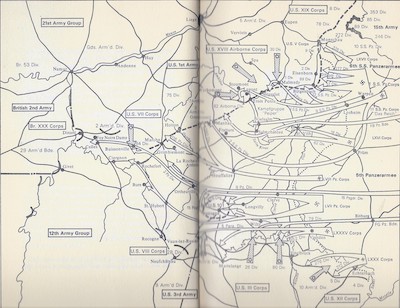

It is not a straightforward war story, rather a hybrid, but clearly based on the author’s actual experiences on the front line in Belgium during the winter of 1944. A small American artillery unit is isolated by the German counter-offensive which became known as the Battle of the Bulge and at the heart of the story is how their leader (by default) Sergeant ‘Bull’ Docker is determined to protect his men and keep his unit intact despite all the hardships, physical and emotional, which beset them . As if this wasn’t enough, McGivern extends the drama by giving a strategic overview of the horribly confusing battle, even providing detailed maps and including scenes involving the infiltration behind American lines of German ‘special forces’ dressed as American military policemen.

Things get very dangerous for the trapped unit when they shoot down – more by luck than judgement – a prototype German jet fighter and the Germans launch an attack to recover the wreckage before it falls into Allied hands. In the desperate fighting, a straggler who has been adopted by the gun battery is killed and later, after the battle, is accused of being a deserter and the final section of the novel is very much a legal thriller to clear the dead soldier’s name.

Soldiers of ’44 is an exceptional war novel, with multiple plot strands expertly manipulated with the authority of someone who has been there and done that. It was said of McGivern that he could ‘fling a situation about like Raymond Chandler and get down to the guts of the thing like Stanley Ellin’ which is high praise indeed.

But then, he should have been used to such acclaim as, in his time, his writing style was also favourably compared with that of Graham Greene, Eric Ambler, Ian Fleming and Kingsley Amis. And despite the ‘harrowing’ response of reviewer Francis Iles, I much prefer, and endorse, the verdict of another distinguished reviewer, my old friend H.R.F. (Harry) Keating writing in The Times when he said simply: ‘Wow; can McGivern write!’

OTHER RIPSTER REVIVALS:

#1: Peter Dickinson

#2: David Dodge

#3: Nevil Shute

#4: War Stories (Part 1)

#5: Walter Satterthwait

#6: War Stories (Part 2)

#7: War Stories (Part 3)