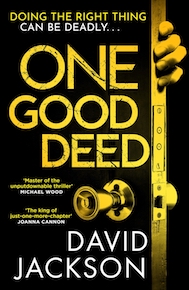

My latest novel, One Good Deed, is about stalking and what can follow from such behaviour if it is unchecked. When Elliott Whiston comes to the aid of a young woman who is being pursued one night, he has no idea what he is letting himself in for. Believing that Elliott is stealing his girl from him, the stalker in my novel grows ever more desperate and unhinged in his efforts to get her back.

My latest novel, One Good Deed, is about stalking and what can follow from such behaviour if it is unchecked. When Elliott Whiston comes to the aid of a young woman who is being pursued one night, he has no idea what he is letting himself in for. Believing that Elliott is stealing his girl from him, the stalker in my novel grows ever more desperate and unhinged in his efforts to get her back.

One Good Deed is, of course, a work of fiction, but in reality stalking is a common crime that often goes unreported. In the majority of cases, the stalker is known to the victim. It may be someone who has difficulty establishing loving relationships with others and who then develops an unhealthy obsession with an acquaintance or colleague. Or it may be an ex-partner who refuses to accept that a relationship is at an end, especially when the reasons for its failure allege shortcomings in that individual.

In Sussex in 2016, a teenager called Shana Grice was stalked by her ex-boyfriend, Michael Lane. Among other things, Lane sent her unwanted gifts and messages, and even sneakily installed a tracking device on her car. Although Grice informed Sussex Police of the harassment, they failed to take it seriously enough, and even went as far as to issue her with a fixed penalty notice for wasting their time. The stalking continued, with Lane following and phoning Grice. When Lane was seen outside her house, Grice didn’t report it to the police because of her prior treatment by them. Later that month, Lane entered her house with a stolen key, cut her throat and set her bedroom on fire.

The inability of some people to relate normally to those around them sometimes leads them to fixate on celebrities, particularly when the public persona or cult status of a famous figure helps to fuel their fantasies. An example of this occurred in the late 1990s, when Ricardo López became obsessed with the Norwegian singer Björk. A recluse with a severe inferiority complex, López made up his mind that he would one day marry the object of his infatuation. He sent her numerous fan letters and expressed his feelings for her in extensive diaries, first on paper and later on video. When he heard that Björk had entered into a relationship, he became so infuriated that he decided she deserved to die. After posting her a letter-bomb containing sulphuric acid, López created his final video. It showed him naked and with his face brightly painted, shooting himself in the head as one of Björk’s songs came to an end. Fortunately, the video gave the police sufficient information to enable them to intercept the letter-bomb and detonate it safely.

Sometimes the activity of stalkers is driven not by idolatry but by hatred for all that their prey stands for. In 1960, a retired 73-year-old US postal worker called Richard Paul Pavlick had developed a severe distaste for the government and for Catholics, and so the newly elected president John F Kennedy was therefore a natural target for Pavlick’s wrath. So intense did Pavlick’s loathing become that he gave away all his possessions, loaded up his car with dynamite and embarked on a quest to destroy his target. Pavlick followed Kennedy around on public engagements and even scoped out the president elect’s family home in Massachusetts. The mistake that Pavlick made was in sending postcards to officials in his home town, declaring that he was about to carry out a momentous act. Noticing that the origin of the postcards matched Kennedy’s whereabouts, the keen-eyed postmaster contacted the Secret Service, who in turn learned of Pavlick’s purchase of dynamite. On December 11, Pavlick sat in his car outside a church at which Kennedy was attending mass, readying himself to detonate his bomb. It was only when Pavlick saw that Kennedy was accompanied by his wife and children that he changed his mind. Several days later, Pavlick’s car was spotted and he was arrested. Criminal charges against him were dropped in 1963, ten days after Kennedy’s assassination, but only because he was ruled mentally ill and committed to a psychiatric hospital.

What these cases and others illustrate is that the reasons for stalking and the types of people who engage in such activity can vary widely. But what they also show is that this form of behaviour can quickly escalate to lethal levels, and is therefore something that should not be regarded as trivial. Legislation has been slow to recognise this: it was not until 2012 that stalking was established as a specific criminal offence in England and Wales. And yet stalking occurs much more commonly than we might think. In an eye-opening study carried out in Australia in 2002, almost one quarter of all the respondents said that they had been stalked.

At one point in One Good Deed, Elliott refers to the stalker as a psychopath. In fact, the desire of most stalkers to form close attachments is anything but a psychopathic trait. Nonetheless, as readers of the book will discover, and as highlighted above, a stalker can prove to be one of the most dangerous and terrifying individuals it is our misfortune to encounter.

Viper (6 July 2023) Pbk £9.99