%20copy.jpeg) The strangest part of lockdown, for me, was when I started receiving visits from someone who didn’t exist.

The strangest part of lockdown, for me, was when I started receiving visits from someone who didn’t exist.

Now, I realise that sounds pretty odd. (Then again, lots of things about lockdown were pretty odd.) At the time, I was deep inside the writing of my ocean-based thriller, The Rising Tide. Work was progressing slower than I’d have liked, mainly because on weekdays my role had switched from author to home-schooling teacher / enforcer / shouter-in-chief. Only at night could I really concentrate on the book. Which is when the visits began.

I should explain that I do most of my writing in our living room, opposite French windows that open onto a tiny garden plot. Here, we’re only fifteen minutes by train from London, so space is tight. Still, that small square of lawn, overlooked by trees (and lots more loft conversions) can feel like the great outdoors if you close one eye, squint a little and tilt your head just so.

At night, it seems a wilder place. During lockdown, even more so. There was less traffic noise, fewer sirens, fewer people.

And that’s when she started appearing.

I’ll reiterate: I know this all sounds pretty odd. (Although, given you’re reading this piece on this particular website, you’ll likely understand more than most.)

My visitor didn’t exist, and yet she seemed as real as someone I might meet in real life. At the time, I had no idea why she’d chosen to descend upon me. In truth, I still don’t. I knew nothing about her except what I could see: a young woman with home-cut hair, different coloured eyes – one brown, one blue – and a furtive but hopeful look.

It’s times like these when my skin furs up. I know something interesting is happening – that sense of a possible story approaching, if only I can grasp its coattails. Thomas Harris once said that authors don’t make up stories, they simply uncover them, a process not of creation but discovery. I agree with him entirely; and I’ve learned, over the years, not to strain too hard when such moments occur. It’s better to feign indifference and pretend, for a while, to look the other way.

At first, my visitor kept to the shadows. But gradually she grew bolder – and closer. She arrived, each night, on a cherry-red electric tricycle, with binoculars slung around her neck, and I wondered at the relevance of those items, and how they formed part of her story. I noticed that she always wore dungaree shorts and oxblood Doc Martens, and listened to music on a vintage Sony Walkman. Her name, I deduced, was Mercy Lake. And I began to realise that she wouldn’t leave me alone until I uncovered the rest of her tale.

At the time, of course, I had other priorities. So I did my best to ignore her and concentrated on the book I was writing. Months later, I returned my attention to Mercy Lake – and found I knew her far better than before.

Heterochromia, the condition that results in different eye colour, can occur naturally due to genetics. But physical trauma also triggers it, almost always via a blow to the head. I knew that an episode of extreme violence had caused Mercy’s heterochromia. I knew, also, that it had led to balance issues – hence her electric trike – and an abiding fear of daylight. Mercy only ever dared to venture out at night. As a result, she led an utterly solitary life.

Despite all her challenges, she refused to remain a victim. To give her life meaning, she watched the fellow residents of her town. And when she saw someone struggling she’d intervene: small gifts, anonymously left, good deeds. It helped her feel closer to a world from which she was estranged.

However well I knew Mercy, I wouldn’t have a story until something upset her fragile status quo. Fortunately, at that moment another character came knocking – someone to challenge and overturn everything she had built.

Louis Carter is Mercy Lake’s antithesis in every possible way. He’s fearless, extrovert, cunning – and Mercy is utterly captivated by him. Although she’ll flee their first meeting, gradually she’ll let him into her world. And when Louis joins her nightly adventures around town, he’ll show her a different way to improve the lives of those she tries to help: punishment for their tormentors; acts of violence that steadily increase in severity.

Mercy will be shocked, not least because – unlike her own – Louis’s interventions work. Small acts of kindness, she’ll realise, are far less effective than fear. It’s a sobering discovery but an important one. Where it would lead the couple, I’d only discover in the writing. A year or so later, I found out.

Author Photo © Sarah Blackie Photography

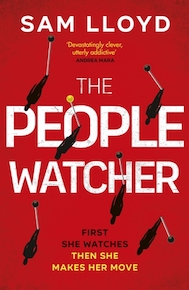

THE PEOPLE WATCHER

Bantam Press, Hbk £14.99

8th June 2023

Read our Review