A contemporary of mine at university – I’ll call him Harry – was an old Etonian, which perhaps explains his morbid fascination with my obscure provincial alma mater: Nunthorpe Grammar School, York. It seemed he was also fascinated by my bow-legged gait, because he nicknamed me ‘the Nunthorpe cowboy’ on the strength of it. I never knew whether this betokened a degree of affection, but I had my answer to that a couple of years after we’d graduated. I saw Harry walking towards me in Fleet Street (I was a journalist by then). When he caught sight of me, a look of near panic crossed his face; he turned aside and pretended to be engrossed in the window display of the tobacconists that stood on Fleet Street back then. Irritated by this, I didn’t see why I should let him off the hook, so I tapped him on the shoulder. ‘Hello, Harry,’ I said. He turned towards me with a sigh: ‘Hopeless to pretend,’ he said, indicating the shop window. ‘It’s not as if I even smoke.’ A very short conversation ensued, and the next time I saw Harry in the street, Iavoided him.

The reason I had mistakenly detected affection was that I didn’t mind being called a cowboy. I’d liked Cowboys ever since watching the American TV series, Alias Smith and Jones, as a boy, and I was never more affected by a celebrity death than when Pete Duel, who played Hannibal Heyes (the ‘Alias Smith’ of the partnership), killed himself in 1971.

Cowboys, I thought, epitomised the virtues of my native county: Yorkshire. They had the Yorkshire taciturnity, arising from professional circumstances where conversational opportunities are limited, either because of remoteness – sheep farming on a bleak upland, say – or anti-social noisiness, as experienced at the coal face or factory floor. (Compare the typical cockney, a market trader who cries his wares, has a patter, indulges in banter.) In this atmosphere of reticence, words are carefully weighed, and good writing is fostered. Here, for instance, is a typically elegant sentence from The Wild West Book, a children’s annual of 1952, written by Arthur Groom: ‘Two shots rang out and the sheepmen who had been acting as sentinels came pounding back, their six-guns smoking.’

About five years ago, I thought I’d like to have a go at writing my own ‘horse opera’, so I began watching cowboy films systematically. Among my favourites for good dialogue (my main criterion when judging a film) were two Coen Brothers films: their version of True Grit starring Jeff Bridges and their Western anthology, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. I’d been thinking of writing a stand-alone cowboy novel, until it occurred to me that I might give a western slant to the next one (the tenth) in my series of novels featuring the railway policeman, Jim Stringer. After all, cowboys go by train almost as often as they do by horse. Take, for instance, the two films called Three-Ten to Yuma, both based on the Elmore Leonard story of the same name, which begins:

‘He had picked up his prisoner at Fort Huachuca shortly after midnight and now, in a silent early morning mist, they approached Contention. The two riders moved slowly, one behind the other.’

(The Old West is never sparer or more poetic than in the stories of Elmore Leonard.)

My Jim Stringer novels progress chronologically, and the tenth one was due to be set in the early 1920s, when what we consider the Old West was still extant. Of course, it was extant in America, not Yorkshire, where Jim is located. But I felt the Atlantic could be bridged.

In a North London pub near my home, I overheard a man talking about an uncle of his – only recently deceased – who’d owned a post office in a Leeds suburb. He was a fan of the Old West, and as a sideline in his post office he sold pulp western books and magazines. As the man spoke, I was formulating my own image of his uncle, having shunted him back in time to the 1920s. He would be middle-aged, slightly unsavoury, out-of-condition (too keen on small cigars), with something tragic about him, because while he made his living dispensing stamps and weighing parcels in a gloomy Yorkshire terrace, his heart was in the Wild West.

He’d subtly affect Western dress – narrow ties, greasy wide-brimmed hat, big belt buckle – and speech. Instead of ‘Yes’, he’d say ‘You got that right’, and he’d combine sub-postmastering not only with selling western books, but also with managing a young sharpshooter who performs in fairgrounds…Because I’d discovered there was a big appetite for Wild West shows in Yorkshire at the time, a legacy of Buffalo Bill’s touring the North in the early 20th Century.

My sub-postmaster would be called Walter; the young sharpshooter would be known professionally as Kid Durrant. Walter, whose attachment to his protegée, goes beyond financial considerations, wants to get the Kid into films, which brings the Kid into contact with a film producer and his beautiful, alcoholic wife. And the Kid is ‘trouble’…

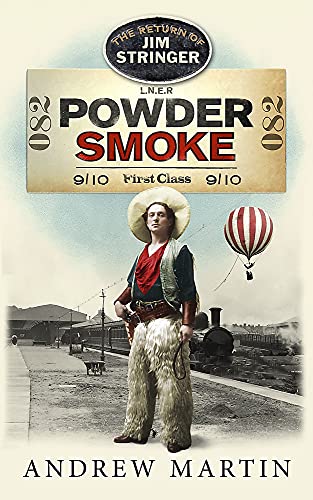

I called my story Powder Smoke, and I like to say, without caveats, qualifications or footnotes, that it’s a Western set in York, Leeds and the North York Moors.

‘Powder Smoke’ is out now in paperback from Corsair.