On 18th October, I gave the annual Richard Lancelyn Green to the Sherlock Holmes Society at the National Liberal Club in Whitehall. The basic text is reproduced here, but as it was an illustrated lecture, some of the ‘sight gags’ have been cut to avoid tedious explanations. – MIKE RIPLEY.

Let me begin with a declaration of intent. I have no intention of trying to teach this audience anything about Sherlock Holmes. I simply would not dare. When I was invited to chair a panel on Holmes’ methods of detection at Marylebone Library, I stressed that I was very poorly schooled in matters Sherlockian, but allowances were made and the evening went well. It must have, because a mere 28 years later I have been invited once again to display my ignorance.

I will avoid that, hopefully, by getting everyone here to agree to one simple premise: Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories laid the foundations of the English detective novel and were the inspiration for its blossoming in the 1920s and 30s which became known as its Golden Age.

Now, may I ask if everyone can agree with that? Good, because then that’s out of the way and allows me to talk about something completely different: the other Golden Age – yes, there were two.

My general thesis will be that for all it is fondly, perhaps sometimes obsessively, remembered and admired these days, in the actual ‘Golden Age’ itself, detective novels were consistently outsold, and by a large factor, by thrillers featuring spies and secret agents who did not so much detect as shoot first and ask questions later, but only if they remembered to.

It was a genre which emerged just as Sherlock was settling in to 221B Baker Street, fed on political fears both real and imagined at home and abroad and which developed a dependable and very popular format. It introduced heroes who became household names, even if only briefly, and none were to have the longevity of a Sherlock. It also produced, in the early 1900s, three novels of distinction and, as one critic has suggested enjoyed its own ‘Golden Age’ in the 1920s, though for spy fiction, as opposed to detective fiction, it was very much a question of quantity rather than quality.

I will attempt to describe some, by no means all, of the leading players who made the spy thriller so popular in the early 20th century and, along the way, how Sherlock might have fitted in to, or wisely kept his distance from, such adventures.

I want to begin in 1870, when the speed and efficiency of the German victory in the Franco-Prussian war shocked Britain. It was masterminded by Field Marshal Helmuth von Molkte, a man who. legend has it, smiled only twice in his life: once when he was told his mother-in-law had died and once when the Swedish ambassador claimed that Stockholm was impregnable.

The rise of Germany and its imperial ambitions led to an arms race on land and sea and where there is an arms race and international tension, there are always spies. Sherlock had some experience of the world of espionage, of course, as recorded in The Naval Treaty, The Second Stain and The Bruce-Partington Plans, and naturally acquitted himself.

But the over-riding fear among British politicians was of invasion and I do not mean the Nigel Farrage or Pritti Patel definition of the word, but rather the full-scale take-over by a foreign power.

It has been estimated by an American academic that between 1870 and 1914, more than 60 stories were published describing invasions of England; 41 times by Germany, 18 by France and 8 by Russia, with China, Japan, the United States and, of course, the planet Mars all having at least one go each.

One of the leading lights in this xenophobic. scare-mongering - and bestselling - trend was journalist William Le Queux who worked, perhaps unsurprisingly, for the Daily Mail.

His initial success came with The Great War in England in 1897, published, impressively, in 1894, which detailed the dastardly invasion plotted by the dastardly French with their dastardly allies the Russians. But his real bestseller was The Invasion of 1910, published in 1906, which had the Germans landing on the Suffolk coast and marching on London.

Fortunately for King and country, the advance guard of elite Uhlans camped at Saxmundham where they made the fatal mistake of sampling the fine ales at The Bell. So well did they sample them that they were in no fit state to continue their advance the next day and the Mayor of London, no less, had time to organise the capital’s defences and the invaders were defeated.

The book reputedly sold more than a million copies as well as increasing the circulation of the Daily Mail which promoted it mercilessly, and was translated into 27 languages. Much to William Le Queux’s chagrin no doubt, a pirated German version by Traugott Tamm appeared almost immediately, though I am told that Die Invasion von 1910: Einfall der Deutschen in England has a distinctly different ending.

Having successfully boosted the fear of invasion, Le Queux turned to whipping the country into ‘spy mania’ – suggesting that at least 5,000 German agents were operating in England – in Spies of the Kaiser in 1909. Interestingly, this collection of short stories includes detailed plans of both ‘the new British Army aeroplane’ and ‘the new British submarine’ – though we all know Sherlock had already dealt with that particular problem.

Paranoia about invasion was also exploited in what is generally regarded the first proper British spy story, or rather the first well-written spy novel, in The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers in 1903. Sometimes disparaged as a novel about sailing with a bit of espionage, it does have the twin distinctions of being the first spy novel to include an element of romance (I won’t go as far as to say sex) and also the only spy novel written by someone later shot for being a spy.

I am not sure whether Holmes could have put up with either Carruthers or Davies for a month in a 40-foot yacht snooping around the foggy Friesian islands, but he would have had the same contempt for the villain of the piece, that most despicable beast: a turncoat Englishman in the pay of the Kaiser.

Apart from the Kaiser, the other perceived threat to national security was provided by anarchists of various hues, including the Suffragettes or ‘window-breaking furies’ as Holmes describes them in His Last Bow, though he implied the Kaiser was probably responsible for them as well.

The anarchist threat was dealt with seriously by Joseph Conrad in The Secret Agent in 1907 and satirically by G.K. Chesterton in The Man Who Was Thursday in 1908, but revolutionary violence was not confined to the printed page. There was a very real threat of violence gently wafting in on the breeze from the East, that of Bolshevism, no better illustrated by the siege of Sidney Street in 1911.

A group of Latvian Bolsheviks, almost certainly not economic migrants, had attempted to rob a Houndsditch jeweller’s, during which three policemen were shot and killed. Weeks later, two of the gang were discovered in Sidney Street in Stepney and decided not to come quietly. Armed policemen supported by the army laid siege and even the Home Secretary, Mr Winston Churchill, appeared on the firing line.

I am sure that Sherlock, had he been on the case, would have conducted himself bravely and concluded matters with less loss of life. I would also like to think that he would have flagged up one of the participants in the event as a subject of interest to the recently-formed Secret Service Bureau, or MI5 as it became known.

I refer to Jacob Peters, or Jekabs Peterss, a Latvian revolutionary who was charged with the Houndsditch robbery but acquitted for lack of reliable evidence. He was not himself involved in the Sidney Street siege and having, remarkably, married the daughter of a London banker, returned to Russia in 1917 to become deputy chairman of the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, which eventually morphed into the OGPU, then the NKVD and eventually the KGB. He became a victim of one of Stalin’s purges and was shot by the NKVD in 1938.

I think Holmes would have said he was one to keep an eye on.

Germans and anarchists were popular villains, but so too was organised crime, no better epitomised by the international criminal syndicate known as The Red Hand, created by Edgar Wallace in The Fourth Plague in 1913, a book which could be seen as something of a trail-blazer for thrillers yet to come.

The Red Hand was Italian, of course, but originated from Siena rather than Corleone and was a sort of special executive for counter-intelligence, terrorism, revenge and extortion.

(That would sound better if I had a white cat to stroke...)

The Red Hand’s agents are in England in search of a Renaissance locket designed and crafted by Leonard Da Vinci in 1387, which just shows what a genius Leonardo was, as he was not born until 1452. Being Da Vinci there is, naturally, a code involved, or rather a secret formula, young Leo having isolated the basic elements of medieval plague, which thanks to the advances in chemistry by 1913, can be recreated synthetically. Once they have the formula, The Red Hand proceed to blackmail the British government, demanding £10 million or they will release the plague virus they have manufactured via flocks of infected pigeons – the Londoner’s deadliest enemy.

It was a staggering demand, as £10 million in 1913 would have bought 3½ Dreadnoughts. In today’s terms, that would be £805 millions, which would buy Sir Philip Green two dozen super yachts plus a centre forward for Manchester City.

The Red Hand’s hideaway is, however, discovered by a trusty servant who clings unobserved to the back of the lead villain’s car for two hours, which may ring a faint bell with anyone who has seen the film Cape Fear.

But the real hero of the book is that great Italian detective and secret agent Antonio Tillizini – tall, slim, dressed entirely in black with a large flowing necktie and soft felt hat, his un-gloved hands long and white and as delicate a surgeon’s – who at one point admonishes his English hosts saying:

‘You English...You have such a fear of melodrama. You are so insistent upon the fact that the obvious must be the only possible explanation!’

When not fighting crime or being a secret agent for the Italian government, Tillizini is also a professor at the university of Florence and caused quite a stir when he delivered, to the Royal Society, his lecture ‘Some Reflections on the Inadequacy of the Criminal Code’ and calmly admitted that he had found it necessary to personally kill ten criminals at various stages of his career.

I cannot imagine Sherlock making such an admission – certainly not at the Royal Society – but in many ways, he could have featured in The Fourth Plague as it required a hero who was a confident of the prime minister (even joining him on the front bench of the Commons at one point!) and of Scotland Yard. It also needed a hero who was impervious to the charms of two strong female characters, who both fall madly in love with the suave super-villain

It is an interesting book in many ways. It had a plot which was ahead of its time yet it also reflected its own changing times. It begins with characters arriving by carriage and brougham but as the pace of the story increases, transport is by fast cars, Mercedes in particular, and our hero has to devise a crude, but cunning way of tracking one a century before CCTV or numberplate recognition. The final shoot-out with the Red Hand gang on the Essex marshes is a siege involving an army detachment and a naval bombardment, which would have been reminiscent of the Sidney Street siege but throughout there is a level of violence and death which Holmes would surely have found distasteful.

There is also a final-page twist in The Fourth Plague worthy of that in The Day of the Jackal nearly seventy years later.

I have spent some time on The Fourth Plague, partly because it was an early example of what Len Deighton calls ‘spy fantasy’ as opposed to ‘spy fiction’ and partly because it was by Edgar Wallace, who simply cannot be ignored when it comes to any appreciation of popular thrillers.

After a disastrous financial start with The Four Just Men, Wallace became one of the most successful and prolific-to-the-point-of-carelessness thriller writers, even exploiting the fear of German invasion, as Le Queux had, in his 1912 novel Private Selby. His rapid churn of novels – not to mention plays, song lyrics and journalism – became something of an in-joke among the reading public. Indeed there is a famous Punch cartoon of a London commuter at a W.H. Smith’s kiosk where the vendor is offering him a book with the caption: “Have you read the lunchtime Wallace?”

With the outbreak of WWI, Wallace got more serious and concentrated on patriotic, morale-boosting journalism, always happy to write features attacking the Kaiser or denigrating conscientious objectors by inventing a recurring character, Private Clarence Nancy.

He did pen several short stories of espionage during the war with one, Code No.2 predicting computer-controlled infra-red photography, and a short series featuring spy catcher Major Hiram Haynes, a born gunman (who) spoke seven modern languages, read two dead ones and could and did quote Browning with remarkable fidelity.

After the war, Wallace abandoned spies and concentrated on crime novels and adventure thrillers, for the simple reason that he had been overtaken in the spy stakes by John Buchan.

The introduction of Richard Hannay from the moment he finds a dead spy in his flat in The 39 Steps in 1915 was a game-changer and its influence can be seen in spy thrillers to this day. It is a well-known story, filmed numerous times – with numerous endings – and I hope I do not need to explain its plot here tonight.

Richard Hannay was a solid, brave, patriotic man, a former major-general who commanded a coterie of loyal assistants, but a character with no vices, no attractive stupidities and almost no sense of humour. He was adept at disguises, having passed as a milkman, a road-mender, a traveller in religious books, a film producer and the chauffeur to a German count, so he had something in common with Sherlock. He could speak four or five languages, including both Highland and Lowland Scots but he had no more Latin than Nigel Molesworth and no Greek at all. He had no time for music other than the wail of bagpipes or the crash of a regimental band.

In his adventures, it must be said that Hannay relied an awful lot on luck and coincidence and was not, with the best will in the world, the sharpest blade in the knife-throwing act. Richard Hannay, though a good man to have next to you on a grouse shoot, was not the most observant of men, in fact decidedly un-observant at times and insisted on what has been called an ‘almost psychopathic modesty’ – neither trait would have endeared him to Sherlock.

One simply cannot see Sherlock haring off to darkest Scotland to solve the problem of the 39 steps, especially when they turn out to be in Kent. But Hannay was not one to solve a problem with brain power when he could use his fists. He was the hero of a new sort of thriller which, unlike the detective story did not revolve around what had happened in the past (usually a murder), but what was going to happen next....

What did happen next has been called the Golden Age of British spy fiction, as well as the Golden Age of detective stories, but for spy stories it was golden only in the account books of publishers, not in the quality of the writing.

In 1920, the year in which Agatha Christie published The Mysterious Affair at Styles, which initially earned her £25 on the sale of 2,000 copies, the latest ‘prince of thriller writers’ (thriller writers, being mostly male, were invariably princes, crime writers tend to be queens), Edward Phillips Oppenheim published The Great Impersonation which quickly sold one million copies and allowed the author to relocate to the French Riviera between Cannes and Nice.

Oppenheim, the son of a Tottenham leather merchant, was to make a fortune out of popular fiction set among the lethargically rich (even his professional spies were multi-millionaires in private life) who enjoyed the finest wines, the highest class of hotels, personal valets, hairdressers and manicurists, yachts and everything else which comprised the Riviera Touch, or at least what Oppenheim told his readers life was like on the Riviera.

The British Library republished very attractive new editions of two of his thrillers, The Great Impersonation from 1920, which had been out of print for 25 years and The Spy Paramount from 1935, which had languished for more than 70 years.

Do they hold up today? Well, the first thing to say is that they are remarkably readable – if, that is, one can get past the casual racism of the first section of Great Impersonation which is set in German East Africa in 1914. The plot will not surprise anyone who has read The Prisoner of Zenda and the modern reader can be permitted a wry smile every time a door or a window is thrown open (there appeared to be no other way of opening a door in 1920) or when the hero thrusts his arms into a dressing gown or a smoking jacket. Most of the action takes place in hotel rooms, during banquets or at lavish society balls on the eve of WWI and in his marvellous study Snobbery With Violence, Colin Watson observed that Oppenheim’s massive success was down to “Selling glimpses of promised lands to others.”

(A scurrilous footnote here: Oppenheim had a yacht on the Cote d’Azur called Echo 1 but known locally as ‘The Floating Double Bed’ - which he retained for his extra-marital affairs. According to Colin Watson, Oppenheim would travel to a chemist in London to replenish his supply of condoms but “whether he was prompted to do so by tact or by residual patriotism one does not know….”)

The Spy Paramount is again readable enough but requires a huge suspension of disbelief in following its fantastical grasp of European politics in 1934. An American spy (naturally of private means) finds himself redundant when the American ‘secret service’ (known as the M.I.B.C. whatever that stands for) is disbanded, presumably for lack of business. Martin Fawley, the rich spy with time on his hands, drifts into Rome and is immediately offered a job by the Italian secret service to spy on the French – naturally along the Riviera, where the casinos, golf courses, yachts and five star hotels are his favoured habitat.

In truth, his first bit of actual spying in the Alpes Maritimes is quite exciting, but soon our hero is trapped in a series of hotel suites being alternatively seduced (delicately) by femmes fatales (all of good breeding) and threatened by shady Germans in between visits from the hotel hairdresser. The settings switch from Monte Carlo to Berlin to London, then back to France and Rome, but the hotel rooms and the idle luxury remain the same until the final reveal of a French secret weapon – “the hellnotter” – which seems to be a death-ray designed to bring down aircraft. By this time, we’ve slipped into Conan Doyle’s Thrilling Tales territory.

What is most fascinating is that the 1934 political background to all this is nonsensical. There is no mention at all of fascism, Mussolini or Hitler and indeed the book predicts a victory for the Monarchist party, dedicated to restoring the Kaiser in the 1933 German elections! The ending, where it turns out that our noble (and very rich, don’t forget) American hero declares that – like a Miss World contestant – he simply wants to work for world peace before sailing off into the sunset, is frankly daft.

Oppenheim did leave one strong legacy, however, for all the trappings of envy he gave his heroes – money no object, beautiful women, fast cars, yachts, luxury hotels, even monogrammed hand-made cigarettes – were to become the trademarks of a certain James Bond in the austere 1950s.

Oppenheim’s success was mirrored by the output of Sydney Horler, who also set many of his spy stories along the Riviera, though is best remembered – if remembered at all – for his Tiger Standish thrillers. Standish, a man of dashing good looks and a footballer of outstanding skill, worked as a freelance spy for something called QI, though I doubt very much he would make it on to the contemporary television quiz unless he refrained from his frequent anti-Semitic remarks and references to ‘stinking Italianos’.

And who could forget the Bulldog Drummond adventures by ‘Sapper’, the pen-name of H.C. McNeile? Although many of us have tried.

In the 1920s, Roger Ackroyd may have been murdered, Lord Peter may have viewed the body, Father Brown may have shown his incredulity and a box of chocolates was almost certain to be poisoned, yet it was the snobbish, sexist and often racist fantasies of Oppenheim, Horler and Sapper which racked up the sales.

One cannot imagine that Sherlock, or even Watson, would have a taste for such low-brow fiction, though apparently more than one British prime minister did.

As the Twenties turned into the Thirties, the puzzles offered by the detective story became even more elaborate, murder weapons more and more bizarre, ranging from daggers made of icicles to church bells, although poison remained the first choice of the homicidal middle-class female. Some of the most famous detective stories still in print today were published then. There was a murder on the Orient Express, much malice aforethought, nine tailors having a gaudy night out and...well, and then there were none.

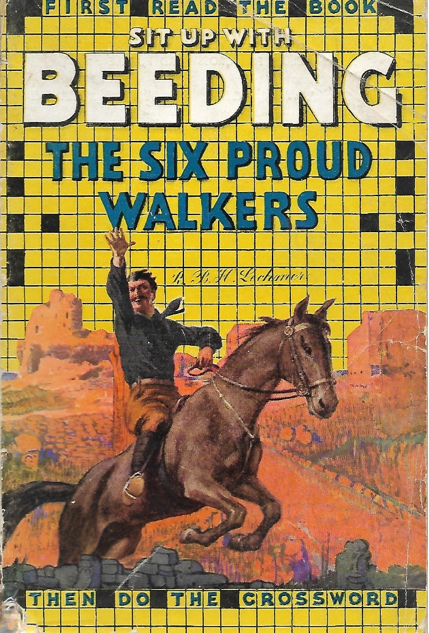

But all of them were outsold in their day by spy thrillers and I want to mention two authors in particular: Francis Beeding and Alexander Wilson, which of course is actually three authors as ‘Francis Beeding’ was the pen-name of the writing partnership of Hilary St George and John Leslie Palmer. As Francis Beeding they wrote fifteen detective novels, two of which were republished about ten years ago, but also eighteen thrillers featuring spymaster Alistair Granby, all of which have been out of print for more than 70 years but which were, in their day, massive bestsellers.

So successful were they that they had their own marketing brand: “Sit up with Beeding” which referenced a newspaper reviewer who had claimed to have sat up all night to finish a Beeding novel. The marketing department at Beeding’s publisher Hodder went even further and produced a paperback version of The Six Proud Walkers which came with its own crossword and readers were urged to sit up with the book and then answer the crossword clues about it.

Beeding’s thrillers followed a set format. Granby, the senior man in British Intelligence would recruit or coerce some decent chaps and chapesses to infiltrate or uncover an enemy spy ring. They would inevitably be rumbled, caught and tied up. They would escape or be freed and a frantic chase using various means of transport would ensue until they captured some enemy spies, tied them up and then went off somewhere, allowing them to escape, at which point a frantic chase would ensue using various other means of transport.

In one case, The Black Arrows (an Italian group of fascists who think Mussolini is dangerously left-wing), our hero ends up in a car chasing a train leaving Venice. In a strange sort of way I could actually see Sherlock jumping into a powerful limousine and shouting “Follow that train, Watson!”

What, in my opinion, puts the Beeding thrillers on a higher plane than the work of Oppenheim and Horler, was their sense of humour. Spymaster Granby is a delightful old buffer on the surface and whenever one of his young male agents goes anywhere near the obligatory femme fatale, he automatically issues the warning “Steady the Buffs”.

But their main distinction is that they were international thrillers written by two guys who had a working knowledge of international politics. Authors St George and Palmer met at Oxford and both went to work for the League of Nations in Geneva. Although they changed the names of Mussolini and Hitler, they were easily identified and the spread of fascism in the Thirties and genuine political tensions were prominent in their plots.

In one book, written by half the Beeding partnership, Hilary St George and co-authored by John DeVere Loder, a Conservative MP, The Death Riders published in 1935, the story begins at the League of Nations when the hero undertakes to infiltrate a fanatical splinter group of Himmler’s SS, who have come to regard Hitler and the Nazis as far too liberal. This is not, however, the most surprising feature of the plot. That is probably the fact that the hero is that most rare of beasts, a Scottish Tory MP.

The usual chases, being tied up and then escaping, occur but the book leaves the reader in no doubt that trouble is brewing in Nazi Germany. For this, the book received a rap on the knuckles from Dorothy L. Sayers when she reviewed it for The Sunday Times in June 1935 and said: “the tone of its references to the German people and their present governors is ill-calculated to promote international good feeling.”

The cynic in me suggests that the introduction of the Nuremburg race laws by the Nazis four months later were also unlikely to promote international good feeling.

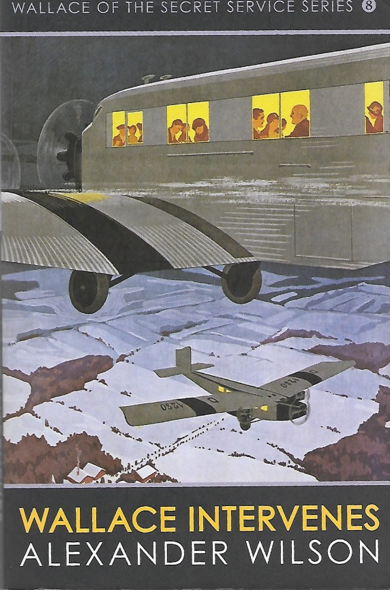

Similar in style – suspiciously similar in some cases – were the very popular novels featuring ‘Wallace of the Secret Service’ by Alexander Wilson.

The series, based on the exploits of Sir Leonard Wallace, the head of the secret service, languished out of print (some might say thankfully) for 75 years until “re-discovered” by actress Ruth Wilson during research into her family history.

In Wallace Intervenes, published in 1939, Wallace has to send an agent into Germany to obtain information from the eminently-seducible Baroness Von Reudath. The secret service seems to be run from a Whitehall basement which is a cross between a gentleman’s club and a doctor’s surgery. Prospective spies sit in a waiting room where waiters draw beer for them until their number is called and it’s their turn for a mission. For his briefing, novice spy Bernard Foster is asked only one basic question by Sir Leonard Wallace – “You get on very well with the ladies, don’t you?’ – before sending him into Nazi Germany.

The rest, as they say, is entirely predictable. Young Bernard naturally falls for the Baroness, gets into difficulties and Wallace has to intervene, showing remarkably agility for a man of his age and who may have a wooden leg (it’s not terribly clear).

One cynical reviewer has suggested that the Wallace of the Secret Service novels could easily have been written by Barbara Cartland if she’d discovered a taste for espionage and, being realistic, the books are really only back in print because Wilson’s grand-daughter Ruth, the actress, made a film about him, having discovered that was a serial polygamist with at least four wives and seven children on various continents. He had been a soldier, a translator in India, a thief and an embezzler and had been imprisoned at least once. He also claimed to be a spy, but in fact was sacked from the translation unit of MI6 in the early years of World War II for embellishing transcripts of radio intercepts and, almost certainly, fiddling the petty cash. For Alexander Wilson, his life really was stranger than his fiction and I cannot see how Sherlock would have fitted into his thrillers.

As Holmes said in the Second Stain: “Now Watson, the fair sex is your department” – and that sentiment alone would mean he would have failed the interview with Wallace of the Secret Service.

I have taken the outbreak of WWII as the end point for the first Golden Age of spy thrillers, though I must make brief, honourable mention of four authors who made important and lasting contributions to the genre: Somerset Maugham with his ‘Ashenden’ stories, Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and Geoffrey Household.

Holmes would certainly have found kinship with Ashenden; been rightly suspicious of many a Graham Greene character; amused by Eric Ambler’s left-wing leanings and probably admired the tenacity and physical fortitude of Geoffrey Household’s anonymous hero in Rogue Male.

The war and the ensuing Cold War were to breathe new life into the spy thriller and a second ‘Golden Age’ could be said to have started with Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale – the book, which one critic said, “put the blood and thunder, especially the blood, back into the thriller”.

As for the Golden Age of the English detective novel, when it actually ended is a matter of interminable debate among afficionados. Personally, I prefer the date 1st April 1947 (it was a Tuesday) which was when Anthony Pratt was granted a patent for his invention, the board game Cluedo, where cardboard pieces replaced many a cardboard character.

Though it is the Hercule Poirots, the Miss Marples, the Lord Peter Wimseys and – hopefully – the Albert Campions which we remember today, in their creative prime they were all overshadowed in popularity by spy thrillers featuring characters quickly forgotten, created by authors now consigned to the history books.

As that erudite crime writer Michel Gilbert wrote: ‘The detective story is the sonnet, the thriller is the ode; it has no formal rules at all. It has no precise framework.

‘Even a second-class thriller will bring in a lot of money. A third-class one can always be made into a film. There is, in fact, no ceiling to the thriller writer’s reward. Membership of the best clubs; a villa in the south of France; if he is really good, he too may end up as Governor-General of Canada.’

So how would Sherlock have survived this tsunami of spy thrillers? Well, of course he did; his legacy is clear in the development of the English detective novel – and I should add, on the American one, and I am thinking specifically here of Rex Stout’s splendid Nero Wolfe stories.

But what sort of a spy would he have made? He was certainly no stranger to the wiles of espionage, and despite what critic John Atkins says in his study of spy fiction , the Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans was not his only brush with the genre.

It was certainly an interesting one, involving good tradecraft as it is known in spy fiction, with Holmes following the trail of the missing plans using a technique which the CIA was to call ‘walking back the cat’ and which showed that Holmes had a knowledge of London stations which would make him an Olympic champion at the game of Mornington Crescent. And of course it helps the spy-catcher if his brother can supply a list of the names and addresses of all the foreign agents in England.

Holmes’ disgust on discovering that ‘an English gentleman’ could sell secrets to a foreign power is perfectly understandable given the patriotic fervour of the time and his outrage would be shared by his contemporaries in spy fiction. Half a century later, following the revelations about Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt, he might not have been so shocked by treachery in the upper classes.

The ending of that story, the trapping of the foreign agent, reminded me of the climax of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and in George Smiley I think Holmes would have found a spy he could get on with.

Sherlock had various brushes with the world of espionage, though sometimes his standards fell short of the ideal fictional spy. In His Last Bow he blows his carefully-established deep cover by revealing himself to Von Bork, where a clever spy would have maintained his cover and continued to feed the Germans false information, though he does give us a good tip – to always copy sensitive documents rather than steal them.

In The Second Stain, Watson is ‘somewhat vague’ on certain details, quite deliberately so in the interest of national security. Good to see someone was on the ball.

The Naval Treaty is very much a how-dunnit as the stolen treaty never makes it into the hands of an unscrupulous foreign power so no actual spies were hurt in the writing of that story, but the interesting thing is that the treaty was with Italy, who was seen as a natural ally of Britain against the beastly Hun and Perfidious French, at least in spy fiction, well into the 1930s.

And there is one other talent Sherlock was famed for which might have come in useful: his skill with disguises.

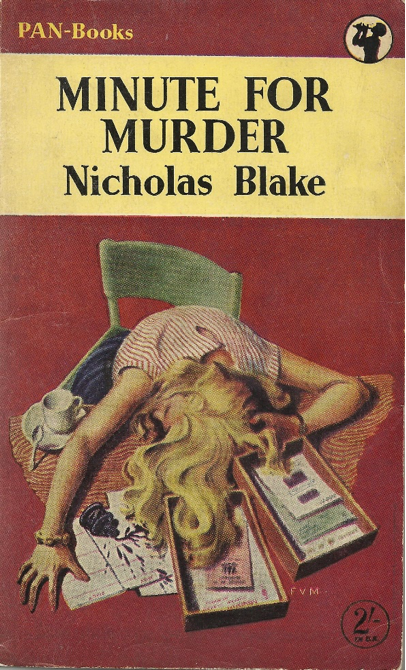

To be fair, two real life spies – Sir Robert Baden-Powell and A.E. W. Mason – both credited Conan Doyle as the inspiration for disguises while on active service. But for the most part, physical disguises were not much used by fictional spies. They often worked under false identities, but only occasionally required the drastic physical disguise described in Nicholas Blake’s Minute For Murder.

A secretary in the ministry of propaganda is murdered and one of the prime suspects in wartime hero Major Kennington who visited the victim the night before her death dressed as a woman in order “to put her mind at ease”. It seems that Major Kennington’s natural bent for transvestism lead to his success as a spy and in the persona of Bertha Bodenheim he had become very close – some might say too close – to the Nazi elite. At one point, Kennington admits ‘A British major masquerading as female – I knew it would get me into trouble eventually’.

Even for King and Country, I simply cannot see Sherlock going that far. At least I very much hope not.

Sherlock did, however, have one thing which most fictional spies did not – a Watson. Spies tend not to have Watsons, they have ‘handlers’ or ‘Controllers’ who brief them on their missions but otherwise they tend to be lone wolves. In many cases, these secret service bigwigs were the brains of the operation and the spy was the Watson to whom things had to be explained; in some cases, very slowly.

In the James Bond era, I can think of only one secret agent who might be said to have a Watson, and that was Johnny Fedora, as created by Desmond Cory and a serious competitor to James Bond until the films came out. Fedora’s sidekick was Sebastian Trout of the Foreign Office, although the relationship tended to be more Jeeves and Wooster rather than Holmes and Watson.

*

So, after this lightening tour – some would say superficial if not downright skimpy – through the early history of British spy fiction, can we draw any valid conclusions about how the Holmes stories compare and contrast? Almost certainly not.

In his day and within his own rules of engagement, Sherlock was a credible fictional spy and his stories are still read today, whereas the massive bestsellers (in their day) of Le Queux and Oppenheim, are blissfully forgotten. Thus one could say that Sherlock Holmes had that absolute essential quality when it comes to being the perfect spy – he survived.

Michael Gilbert in Crime in Good Company [Constable, 1959]