I like to write unreliable narrators—principally because in my job as a criminal barrister the one leitmotif is that no witnesses (narrators) are ever truly reliable. It’s in the nature of human beings to be unreliable. In the courtroom we make a witness (even jurors) take an oath or make an affirmation promising to tell the truth (or return true verdicts)—because we recognise that people sometimes lie.

But lies are only half the story. The other half is truth. We speak these days not of single truths, but of multiple truths—even individual truths where people say ‘this is my truth.’ Well what of that? Can there be multiple truths? We know from scientific evidence that people are terrible historians of events that they witness first-hand. Without a video reminder, we get basic facts wrong. Hair colour, height, skin colour, time, date, distance, clothing and on the list goes. In 30 years of doing trials I have never once encountered honest witnesses describing the same event in the same way with the same details. If they do—it’s usually evidence of collusion.

The reason for this is of course, memory. The brain lays down memory in a very unpredictable way. External factors affect the way in which we remember things. If the event is traumatic the brain can mis-remember key facts. If the event is insignificant, the brain may not store it at all.

Does it matter? Well in criminal cases, your verdict of guilty or not guilty is a function of how evidence is viewed. If you accept the prosecution case, you will say guilty. The interesting thing is that this process creates truth from uncertainty. Guilty means that a defendant committed the crime. The moment the verdict is delivered that becomes the truth—whether it is or not in fact true. It’s a fiction that we construct in order to function. The judge sentences the defendant as if that verdict is the truth (and does it even if they don’t personally believe it to be true), and the defendant is processed as if he is guilty.

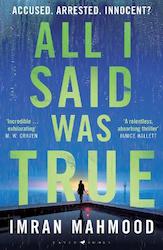

So then the narrator in the novel just reflects that condition. People do their best to tell the truth but can't promise more than that. In All I Said Was True, Layla is giving an account to police. There’s a dead body in her arms. She claims the murderer is not her but someone called Michael. The police don’t believe Michael exists. As readers we determine whether her account holds water. But there’s more than truth at stake. Culpability is at stake too. Layla tells us that we are not free agents. We don’t act in accordance with free will. Free will is an illusion. It sounds like madness. But in fact, Layla is in good company. Steven Hawking for example believed that it was highly probable that we did not exercise free-will. That all we have is the brain creating the sense that we have agency in order to protect ourselves from the misery of living a life on train-tracks. Layla’s question to police is whether it matters if she is the murderer or not. What if we can't help what we do? What if we do the only thing that we can ever do because to do other than that is impossible, because then we wouldn’t be us?

Ultimately, we do with narrators what we do in life. We take our narrators at face value, I think, until they do something that abuses our trust. We assess, we judge, and we assess again as we go along. And finally, I think we end up with at least this one core truth. That a person isn't a fixed and immobile object. He or she is a mutable, ever-changing kaleidoscope—one day reliable—one day not. Just like you and me. There are days when I like me more than other days. There are days when I am boring and others when I am angry or quiet or melancholy or ecstatic. And I find it comforting that I am so changeable—that I can escape the me of today, tomorrow, if I want to. I like stories that are like this too because a changing, undulating, breathing story feels alive. And nothing is as good as that.

Photo © Bill Waters

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. Hbk £14.99 July 21st, 2022