I am a fan of Ian Fleming’s Bond books more than I am of the films. The early novels are very post-war, almost gritty. On the written page, Bond is a disaffected ex-combatant who drinks to forget the horrors of war (and of his new job), and who even sweats. He feels more real than screen Bond and is, of course, often said to be based on Fleming.

Which is, perhaps his problem. I read my first Bond novel, Casino Royale (Fleming’s own début) when I was only 15, but I instantly felt that agent 007 might have what we now call “issues”.

Inevitably I fell in love with Vesper Lynd, Bond’s smoulderingly sensual spy colleague. The spell wore off, though, when she let herself get kidnapped by having her wide skirt pulled up over her head like a sort of fabric tulip. I thought, “She’s a trained agent but she lets herself get snared in her skirt? How rubbish is she at martial arts?”

We later learn that the kidnap was a put-up job because Vesper is a traitor, but even so … It was as if Fleming was simultaneously too gentlemanly to imagine a lady getting bludgeoned, and yet too macho to accept that a woman might be good at unarmed combat.

And so the Bond Girl was born, that beautiful yet fundamentally unreliable woman who – let’s face it – is basically a bit thick. Or if she’s intelligent, she’s bound to mess things up.

In the second novel, Live and Let Die, Solitaire is a psychic who will lose her powers if she sleeps with a man. And once Bond has seduced her then saved her from the forces of evil, she is nothing more than his nurse on his post-mission holiday. It’s a bit like a woman giving up her career for marriage – very 1950s.

In Moonraker, Special Branch agent Gala Brand is skilled enough to infiltrate Hugo Drax’s organization, but as soon as Bond gives her a tricky job to do – sneaking a look at Drax’s personal notebook – she bungles it.

In Doctor No, Honeychile Rider has an “extraordinarily erotic” body but the mind of a child. The Goldfinger girl, Jill Masterson, is being paid by Auric Goldfinger but betrays him with the first good-looking man (007, of course) who walks in the room. In the same novel, the gloriously named Pussy Galore is a ruthless gangster, a lesbian to boot, but switches sides – both legal and sexual – as soon as Bond turns on the charm.

The list could go on.

There are reliable women in the Bond books, but they’re the ones 007 doesn’t sleep with. Moneypenny is the rock at the heart of M’s office, but she’s a mother figure, too old and familiar for Bond to seduce.

May, his housekeeper, is ancient and sexless and can therefore be relied upon to cook perfect eggs and ask no questions about the lifestyle which causes her employer to come home with bruises and bullet holes.

Rosa Klebb, the Soviet spymistress, almost kills Bond at the end of From Russia With Love, which is why she has to be a hideous lesbian: no sexily available lady would be that dedicated and skilled a secret agent.

This may sound like a predictably 21st-century PC reading of Fleming’s books, a modern viewpoint imposed on vintage fiction. But at the very least, this distance in time and mores gives the reader a detached view of what the author was doing. In the same way, I am fascinated by the absence of sex in PG Wodehouse. In a Bertie Wooster story, the atmosphere is fluffy and carefree because no one ever sleeps with anyone else’s spouse or intended. With Fleming it is the opposite – hormones drip off the page.

Fleming himself was apparently a quick-fire seducer, capable of propositioning a woman two minutes after offering her the first cigarette. This lack of conversational foreplay may explain why his female characters feel so unconvincing. Even PG Wodehouse’s flappers and aunts seem less stereotypical.

And Fleming’s war record might hold the key to all this. After a short excursion into France in 1940, he spent almost the entire war as an armchair secret agent in the Admiralty. He worked closely with American intelligence services, and is credited with helping to create the CIA. But most of his war was spent dreaming up crackpot schemes – an agent could be landed on a Dutch beach and bury himself in the sand to observe Nazi shipping, things like that.

Unlike Bond (who was conceived in 1953), Fleming did not carry out these missions himself. Meanwhile, however, he knew that real women were being sent out from London to risk their lives. The Special Operations Executive sent about 40 female agents into Occupied Europe, usually to hook up with Resistance networks. Around 50% of the women were killed. Some are now well-known names – Noor Inyat Khan, Krystyna Skarbek and Violette Szabo. I was recently driving around France when I came across a small monument in a wood near Limoges, marking the spot where three women I’d never heard of had parachuted into France – Marie-Louise Clorec, Pierrette Louin and Suzanne Mertzisen. All three died in Ravensbruck concentration camp.

Fleming must have known about many of these women, and surely it must have gnawed at his manly conscience to be sitting in London with his smart uniform and silver cigarette holder while women – the “weaker” sex – were parachuting into French forests.

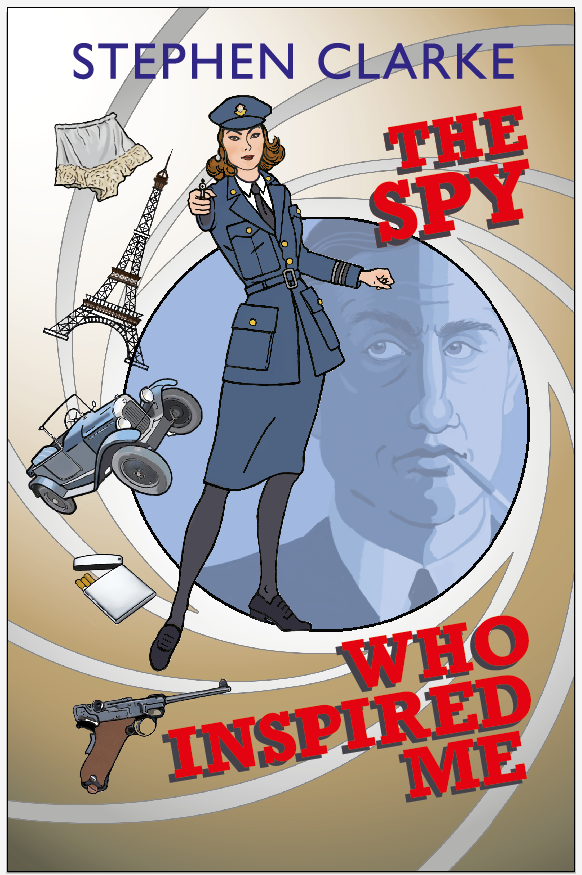

This was why I thought it would be fun to write a novel, The Spy Who Inspired Me, which mischievously dumps an armchair Admiralty officer called Ian Lemming (definitely NOT Fleming) on a Normandy beach in April 1944.

He shouldn’t be there and wants to go home, while his traveling companion Margaux Lynd (no relation to Vesper) is a dedicated agent with a mission to accomplish. And so she teaches Lemming about the real, dirty business of being a spy – the bad food and lack of baths and cigarettes, the constant danger of discovery. As an escape from this harsh reality, he starts to imagine a male spy who lives in luxury and can swan around announcing his name to everyone without getting killed. Bond (or someone very like him) is being born.

All this is, of course, just literary playfulness on my part. PG Wodehouse even pops up in the novel (he was interned in a Paris hotel in 1944). My intention is to tease Fleming, a writer I admire, but also to pay my respects to the real secret agents who helped to rid France of its Nazi occupiers.

So the main difference between The Spy Who Inspired Me and the Bond novels that inspired it is that the central woman character is actually reliable. Oh, and she wears unglamorous second-hand French underwear, because any hint that she’s not an ordinary French woman will get her tortured by the Gestapo. That was the un-Bondlike reality of spying in 1944.

The Spy Who Inspired Me

Published by pAf 30 September 2021

Paperback £8.99 and eBook