During China’s Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), authorities used a palm print to convict a burglar. Since then, law enforcement bodies have strived to find the perfect clue.

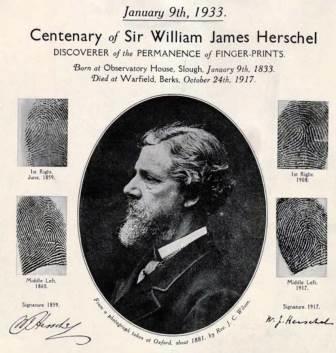

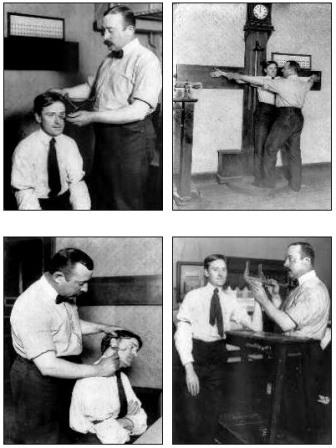

The English first used fingerprints in 1858, not in England, but in India. Sir William Herschel, Chief Magistrate of the Hooghly district of Bengal, used thumb prints for illiterate natives to sign official documents. Despite Herschel’s incredible modus operandi, it was ignored by the English. In 1870 Alphonse Bertillan, a French police clerk, devised a system of identifying criminals by measuring their limbs. This method was adopted by most European police forces (including the Yard) until the end of the nineteenth century. It became known as the Bertillan system with the more technical term of Anthropometry. New Scotland Yard finally introduced fingerprint detection in 1901.

A detective’s most powerful tool is trace evidence. It was established by a French scientist called Edmond Locard. He stated that `Wherever he steps, whatever he touches, whatever he leaves, even unconsciously, will serve as a silent witness against him’. For the past hundred years, police forces have adopted Locard’s philosophy with great success.

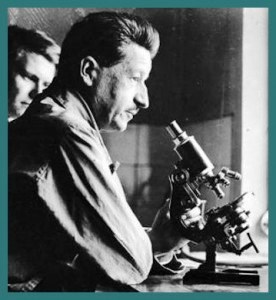

Regular breakthroughs have made crime fighting a recognised science. In 1987 I escorted the body of a murder victim to the Lambeth police laboratories. Scientists were experimenting with a new technique. The theory was, that in a case of strangulation, lasers could expose a strangler’s fingerprints about the victim’s neck.

On a previous occasion, a police constable was patrolling a high street where a car aroused his suspicions. He wrote the registration number on the palm of his hand. Two days later a local bank was robbed; suddenly, the number became an essential clue. But, since recording the registration, the constable had taken three showers and all trace of the vital evidence had vanished. He was taken to Lambeth laboratories and a laser was beamed onto his palm. The missing number immediately came into view. Scientists also experimented with lifting DNA from the air. The theory was, if a person had been in a room during the past-hour, his or her DNA was present in the ambient air. For decades, scientists have studied the Iris of murder victim’s eyes, believing that the murderer’s image has been captured. To date, there has been no breakthrough!

Recently, the Met police laboratories have been renovated, and are now a state-of-the-art detection unit. The fourth and fifth floors contain DNA clean rooms, making the risk of cross contamination impossible. Lower floors house highly specialised units, such as Digital and electronic Forensic Services (DEFS). Laptops and mobile phones are interrogated in the search for truth. No matter what precautions are taken, computers always hold hidden files which can easily be recovered. In the case of mobiles, the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) is used. By triangulating phone masts, officers can identify a person’s exact position at an exact time. Number Plate Recognition (NPR) is another major tool. CCTV cameras and mobile units can confirm a vehicle’s route. NPR is also connected to the national police computer, giving access to criminal intelligence and driver’s convictions. Today, police officers can be miles from their base, and have up to the minute data transmitted to them. No longer can suspects hide behind false names and dates of birth. The C71 Biometric scanner is handheld, and can scan fingerprints, read Iris’s and identify facial recognition.

This modern technology is controversial and begs the question, how far will scientists be allowed to go? India is currently building a biometrics’ data base to hold 1.3 billion identification files. Registration to the data base is mandatory for every Indian resident. To date, 90% of the population have complied and provided both, personal fingerprints and Iris data. Nonregistration is not only illegal; it stops the citizens from claiming pensions and benefits. To claim, they must hold an Aadhaar registration number, which can only be issued once the person’s fingerprints and Iris are recorded. Perhaps, at the end of the day, the search for the perfect clue may be confounded by Human Rights issues.

Corrupt Bodies: Death and Dirty Dealing in a London Morgue

by Peter Everett and Kris Hollington

Published by Icon. £16.99 hbk. 26 Sep 2019

— Kris Hollington is a bestselling author and ghostwriter;

several of his books have been adapted for TV.