From the beginning, I thought of The House on Half Moon Street as the first in a series. Part of the reason is that, as a reader, I often feel sad at the end of novels because I know I’ll miss the characters. What did they do next? Did their triumph satisfy them as much as they hoped? Do they all still know each other? But in a series, I know they’ll be coming back, so I can inhabit their world again.

Writing a series has its challenges. You’re asking the reader to come with you on a long journey, because the failings of your characters won’t be completely overcome in one story or by solving this particular crime. In fact, everything you write counts twice, once for the story you’re telling, and again for the long arcs that go across multiple novels. Characters have to live with the consequences of their actions – physical, emotional and mental – from book to book.

For a crime series in particular, the central character needs a plausible reason why they’re involved with all these murders. It might be because of their job or their place in society, or it might be because they’re Jessica Fletcher from Murder, She Wrote. Many great books have featured policemen and private detectives, but I didn’t want to go in that direction. In particular, I didn’t want my central character, Leo Stanhope, to be too competent. While I love the works of Doyle and Christie, I find Holmes’ and Poirot’s brilliance sometimes drains a little human drama from the story; the detective arrives, solves the crime and then leaves, apparently untouched by pain, grief or frustration. I aspire more to the work of Raymond Chandler or Walter Mosely. When their heroes solve a crime, it’s on their doorstep and they can’t just walk away. And they’re smart but they can’t identify the murderer by sniffing cigar ash. They have to muddle through like the rest of us.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of writing a series is how to explain things to new readers without giving away the plots of previous books. As much as possible, I focus on the emotional consequences rather than summarising the events. Of course, I’m still left with the problem of how to introduce factual information to new readers without repeating myself. For example, Leo wears a binding he calls his ‘cilice’, and for every novel I have to find a new way to explain that. I quite enjoy the challenge though.

There are certain tropes in crime series that I’m keen to avoid. One is the idea of a sidekick; someone who apparently has nothing better to do than hang on the exposition of the central character and occasionally get punched. The nearest I have to that is Rosie Flowers, but she’s nobody’s sidekick. She has her own reasons for doing what she does and is absent from the novels for chapters at a time because she has other responsibilities – children and a shop – and can’t just drop everything for Leo. She and Leo keep secrets from each other and have a fractious relationship, not least because she might actually be better at detecting than he is. Some readers have even suggested that a future novel might focus on Rosie, with Leo helping her instead of the other way around.

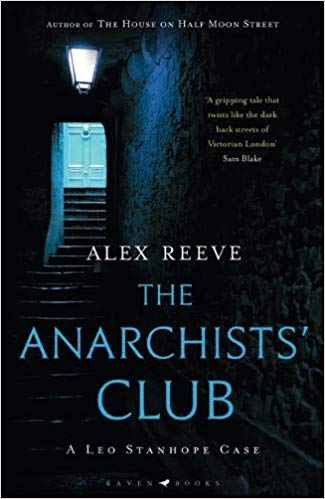

More minor characters can recur too, but only if there’s a good reason. If they don’t have things to do, no matter how much you love them, it’s best to leave them out or you risk making the story appear contrived. Equally, sometimes you have to leave them out for precisely the opposite reason. In my second novel, The Anarchists’ Club, I introduce a character who I’d like to keep for future novels, but for book three, which I’m writing now, he’s too convenient, too perfect. He would make Leo’s life too easy. So, I’ve sent him away. He’s gone off to do something else and will be back in book four.

Finally, there’s the ‘greatest hits’ problem: the temptation to repeat what’s worked in the past. Just because everyone liked your heroine getting drunk in the first book doesn’t mean she should do it every time. For example, The House on Half Moon Street features certain scenes, including a brief sex scene, because they’re necessary to carry the emotional weight of the story. But The Anarchists’ Club doesn’t have so much as a peck on the cheek in it, because the emotional weight is elsewhere, on parenthood and family. At heart, this is what I love most about writing a series: each book is unique but is part of a greater whole.

The Anarchists' Club (A Leo Stanhope Case)

Raven Books

Hardcover, 2 May 2019