.jpg)

Twenty and living at

home, what I scraped together from a call centre job seemed then to be enough

to buy whatever I wanted, especially as whatever I wanted was a few jars down

the local and as many books and CDs as I could lay my hands on. This was a

different time—a small town might have an HMV and an Ottaker’s right across

from one another, and they might happen to be on your journey home, providing

easy browsing opportunities on the way.

If I read book reviews

in the press at all, it wasn’t to garner opinions on new releases, but rather

to scour them for those moments when the reviewer might draw parallels with

other books or other writers. This to me was the nitty gritty—these comparisons

felt like the really personal stuff, the stuff the reviewer really wanted you

to listen to.

More often than not,

I’d forget about whatever book was being reviewed and just latch onto the

comparisons. This is how I found Newton Thornburg. For the life of me, I can’t

remember what the book being reviewed was, but it must have been a 70s American

crime novel, or one set in 70s America at least, as the writer found

similarities in its exploration of the post-Vietnam post-Watergate American

psyche to Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers

and Thornburg’s Cutter and Bone.

This was new information

to me, new names to scour the shelves for on the way back from work. The Stone

was easy. Picador had recently put out new reprint editions of a lot of his

books, and Ottaker’s had Dog Soldiers

nestled there as if it had always been waiting for me. Thornburg not so much.

I searched the crime

and general fiction sections for any sign of him and then searched again,

because imagine asking at the counter only to find you’d missed the thing

sitting there in plain sight—that way abject mortification lies. The staff at

Ottaker’s were always incredibly helpful, and though they hadn’t heard of the

book or of Thornburg, they gladly looked it up. Yes, Cutter and Bone, there it was. A hardback from Heinemann in 1978,

no longer in print. A paperback from Simon and Schuster in 1988 as part of

their Blue Murder range (a selection edited by lifelong champion of neglected

crime fiction, Maxim Jakubowski, which had put out volumes from Dolores

Hitchens, David Goodis, Leigh Brackett, and William McGivern among others). Unfortunately,

they couldn’t source a copy.

This was worse than

being told the book didn’t exist and the reviewer had been pranking their

readers. It was out there in the world, but I couldn’t get it. The movie of my

book-buying life would cut to a musical montage of me skipping through

second-hand bookshops on Charing Cross Road as the seasons slowly turned,

ending with me dashing out of the rain with a folded paper over my head to find

a knowledgeable store-owner who had a hardback upstacked somewhere.

I’ve never been much of

a skipper or a dasher. We were on the cusp of a new millennium and online

shopping was in its nascent form, still something of a niche industry. But it

was there. I don’t remember if I knew about Amazon or Abebooks at the time, but

eBay was there and after periodically searching all combinations of Newton and

Thornburg and Cutter and Bone over a few months, a copy was finally listed. In

a bookshop in New Hampshire. That didn’t offer international delivery. They

did, however, have a link to their own website, which had an email address, and

after some negotiating in which I agreed to pay an embarrassing amount of

postage, one copy of the Little, Brown hardback US 1st from 1977

landed on my doormat in pristine condition.

Feeling like I’d slayed

a dragon, I devoured the thing in a day. Then I had to read it again

immediately. At the time it was hard to determine how much my love for the book

was tied up in the quest and subsequent glory of actually finding a copy, but

the years since have made it clear that it is a straight up masterwork. Yes, at

its heart it was a murder mystery—the dumping of a body is witnessed, a suspect

is identified, a plan is hatched. It features two colourful leads—a worn out

gigolo with nothing in the bank, and a one-armed, one-legged, one-eyed Vietnam

veteran who excesses Thornburg never allows to topple over into cartoon

territory. But there are a million murder mysteries. Thornburg’s writing was

elegant and fluid, and his plotting never missed an opportunity to surprise,

usually in some soul-scarringly melancholy fashion. The first line is up there

with Crumley’s opening to The Last Good

Kiss, and Thornburg’s ending, right down to its final sentence, remains the

most perfect dénouement I’ve ever read.

This was to be the

first of many such quests and rabbit-hole adventures over the years, and I’ve

consistently found myself drawn away from the centre of the publishing universe

to the fringes and frayed edges. Sometimes, the books you find at the end of your

searching might not live up to expectations (and the act of searching itself

can so elevate expectations), but often the writers uncovered feel like veins

of gold that should be opened up to everyone.

Some writers begin at

the hems of the mainstream and forever remain there, others find themselves

pushed from the middle to the outside by time and neglect (suggesting the

process can be reversed and they can be restored to the popular pantheon). I’ve

found many favourites there.

Jerome Charyn’s Isaac novels and George Baxt’s mysteries

featuring the gay black P.I. Pharoah Love made noise in their day but are

sorely overlooked now. Walter Mosley led me back to Chester Himes and into an

exploration of less well-known African American crime writers like Rudolph

Fisher, Julian Mayfield, Clarence Cooper Jr, and Vern E Smith.

Even geography can do

it. Doris Gercke is a popular and well-received writer in her native Germany,

but only one of her novels (the slender, unsettling, and very good How Many Miles to Babylon) is available

in English, and even then not always cheaply or readily.

Frederic Brown, Kay

Boyle, Alexander Baron, Barbara Comyns, Owen Cameron, Sylvia Townsend Warner,

Gerald Kersh, Vera Caspary, James Hadley Chase, Bette Howland, Don Carpenter,

Kent Anderson, Joanna Russ, Jean-Patrick Manchette, Henry Green, Elizabeth

Harrower are an unspeakably random selection from a million other names I want

to shout from the rooftop, some being brought back into the light quicker than

others as time goes by.

There seems no rhyme

nor reason why some writers’ legacies are better protected in the mainstream

than others. It certainly has nothing to do with the quality of writing. Ross

Macdonald’s classic mysteries are easily available, but his wife Margaret

Millar is mostly relegated to compilation editions typeset in nearly unreadable

ways. She was critically and commercially successful in her lifetime and every

bit the equal of Macdonald (Millar was his name—he changed it professionally

because his wife was already so well known). It isn’t just older books. How is

Maggie Estep’s brilliant Ruby Murphy trilogy (Hex, Gargantuan, Flamethrower) out of print only 13 years

after the last one was published? My beaten up ex-library copies wear their

spine labels proudly.

What makes the

neglected attractive? I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t an innate satisfaction

in the process of discovering writers who are no longer widely read. Even

though you want everyone to read them, there is also an incongruous proprietary

pleasure to having them to yourself for a while. If we all read the same

things, we’ll end up thinking and writing the same things.

Perhaps it is just my

long-held suspicion that any book I ever managed to get published would itself

probably end up in the outer reaches sooner or later, and I wanted to know my

fellow denizens before I got there.

Newton Thornburg was

saved. A couple of years after I found Cutter

and Bone, I could have walked into any decent bookshop in the country and

found it on their shelves as Serpent’s Tail reissued it and two of his other

best works (To Die in California and Dreamland). Although out of print

physically, Serpent’s Tail continue their good work and have all but two of his

novels available in digital.

So raise a glass with

me to all searchers past, present, and future who truffle out the good stuff,

and those who strive to bring it back into print. And if you’re reading this

twenty years from now (it’s 2019 and Britain is on the verge of punching itself

in the face again, as it no doubt is when you are too), have a search on

whatever technology binds you to the world, go look for some of these books if

they remain underappreciated.

Hell, go look for one

of mine.

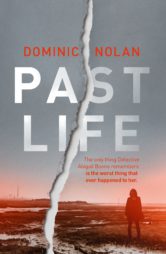

Publisher: Headline (7 Mar. 2019) HBK: £18.99

Read SHOTS' review