It’s difficult for most

of us to imagine what life was like in the England at the turn of the 19th

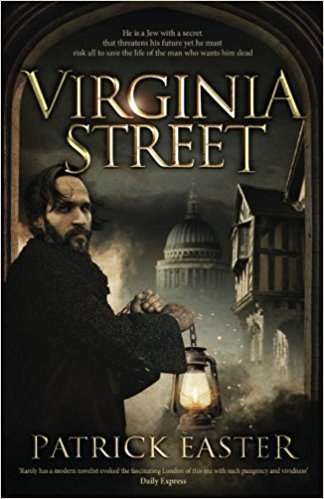

Century, the period in which Virginia

Street was set. Law enforcement was largely a matter for the individual

who, if he or she felt sufficiently aggrieved, was expected to produce the body

and the evidence before the courts. The concept of a professional police was

frowned on and regarded as means of political suppression as was the case

across the Channel in revolutionary France. Crime prevention was to be left to a

rag-bag assortment of folk of varying degrees of incompetence, including the

militia, a few part time constables attached to magistrates’ courts – like the

Bow Street Runners – and a few, and mostly elderly, parish appointed watchmen.

None were required to actually investigate crimes.

Small wonder, then, that

violent crime should be so prevalent on the streets of all major towns in the

UK in the last years of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th

Centuries. Nor was the situation helped by the huge social and political

upheavals of the period. The years of war in Europe and America, the 1798 uprising

in Ireland and its brutal suppression by the army, and the continuing suspension

of Habeas Corpus four years earlier

all played a part in the disruption of daily life. According to Patrick

Colquhoun, a magistrate in London at the time, ten thousand men in the capital

(of a total population of under a million) got up in the morning not knowing

where they would sleep the following night. On the Thames, a ship bound for the

Port of London would typically lose up to a third of its cargo to piracy.

In essence, by 1800, the

country was bust and was facing the threat of invasion from across the channel

every bit as daunting as that of 1940. A French raiding party had already

succeeded in landing on the West coast of Ireland and was to lead (Prime)

Minister Pitt in his attempts to abolish the (almost exclusively Protestant)

Irish Parliament and bring the island into full union with the UK. But if his

initiative was meant to bring to an end the simmering resentment that existed

between the two peoples, it didn’t work. The open sores of the 1798 uprising

ran too deep.

The thousands who left

Ireland in the wake of the uprising and settled in London and elsewhere in

search of work were regarded with a sense of loathing and suspicion and, along

with Jews and Lascars, occupied the lowest ranks of the social order.

Into this toxic atmosphere

stepped a Portuguese Jew, a man named Emanuel Lazaro who, for nearly thirty

years had served the largely Irish community in and around the Shadwell and

Wapping areas of east London as a Roman Catholic priest. His base in Virginia

Street near the junction of the modern Highway (then called the Ratcliff Highway)

was a small, non-descript building that carried no outward sign of its purpose

as a chapel. To have done so would have been to invite the attention of the

mob. Yet Emanuel hid a secret that had the potential to destroy him and which

forced him to live his life in isolation from Jews and gentiles alike.

When a young Irish

Catholic was attacked and beaten outside the door of his church, it set in

train a series of events for Emanuel that were to threaten his life and the

lives of those around him. And when, three weeks later, the body of one those

responsible for attacking the Irishman is found face down in the Thames, things

go from bad to worse as Emanuel seeks to discover the truth and comes face to

face with an old enemy, a man Emanuel has known since the former was a child.

The relationship between

these two men forms the central theme of the book and when his enemy is charged

with a murder he didn’t commit, it is Emanuel who holds the key to his

survival. Under the seal of the confessional, the priest has learned the

identity of the real killer. It is a secret he is bound to keep yet if he does,

an innocent man will die. But the alternative is equally hard. To tell what he

knows to be the truth would not only lead to his own downfall but perhaps the deaths

of many.

Editorial note

A good deal of the story

told in Virginia Street, is true or

at least as close to the truth as any historical account can ever be. The

plight of the Jews and the Irish in England has not, I hope, been glossed over.

Nor have the dreadful events in Ireland in. the Summer of 1798 been short

changed. Many of the characters who find their names appearing in the book were

real people making decisions in the light of their available knowledge. As for

Emanuel, very little is known of him to history. While it was (and remains)

unusual for Jews to practice the Christian Faith, it was a legal requirement in

Spain and Portugal that every citizen should be a fully baptised Christian –

effectively a Catholic. And as evidence of their apostasy, Jews were required

to attend Mass every Sunday. While there is every reason to believe that Jewish

citizens obeyed the law, there is at least a suggestion that they continued to

follow their Judaic faith in the privacy of their own homes.

Emanuel appears to have

been different but, in leaving the faith of his ancestors, he was effectively

shut off from his own people and must have led a rather lonely life in London.

Virginia Street, (Oakdown Publishing) an historical crime thriller by Patrick Easter

is available from

Amazon

About the author

Patrick Easter is the

author of four previous novels that follow the fortunes of Tom Pascoe and the

newly formed Thames Police based at Wapping. Patrick was himself a former

police officer in London and for part of his service was based with the river

police.

On retirement he became

a freelance journalist for international publications covering advanced traffic

control systems throughout the world. His first book, The Watermen, was

published to high. Acclaim in 2010 and was followed by The River of Fire, The

Rising Tide and Cuckold Point. He lives in Sussex with his wife and their two

dogs.

He can be reached

through his website – www.patrickeaster.co.uk or followed on FaceBook (Patrick Easter –

Crime Writer)

Virginia Street was

first published in April 2018