By his old contubernalis[1] Mike

Ripley

{Portions

of this tribute are reproduced from Mike Ripley’s ‘Appreciation of Colin

Dexter’ written for Bouchercon 26; updated on the death of Colin Dexter on 21st

March 2017 and with previously unseen photographs.}

Prolegomenon

1 ACROSS: Left with a penny.

Sounds right to Nero.(5,6)[2]

It

began over thirty years ago on a family holiday in Wales, where of course it

was raining.

Having no doubt already explored the

charms of the region’s ales such as Buckley’s or Felinfoel (known locally as

“Feeling Foul”), our hero, bored and trapped indoors by the unforgiving

weather, picked up a detective story which had been left in the holiday home by

previous tenants, and began to read.

No one is sure at exactly what point the

reader abandoned the book, but abandon it he did, with the words “I can do

better than that” (or similar), and, reaching for pen and ink, he did; though

for many years he refused to divulge which detective story had inspired

him, out of desperation, to do better.[3]

1.

What

travelled home from that wet Welsh holiday with the Dexter family were the

first chapters of Last Bus To Woodstock which begins, appropriately enough, on

the 29th September; St Michael’s Day and also Colin Dexter’s

birthday (and, ironically, mine too.)

Those chapters were placed in a drawer in

the Dexter house in Oxford and promptly forgotten until, perhaps six months

later, whilst searching for a cufflink or a sock (the forensics are unclear),

they were discovered by the author who read them over and thought to himself:

“That’s not bad”.

And so, dear reader, he finished it, writing

in the evenings (but only after The Archers had finished) and when the

manuscript was completed to his satisfaction, he parcelled it up and submitted

it to publishers William Collins, the home of the legendary Collins Crime Club

imprint.

A long six months went by and answer came

there none from London.

Feeling somewhat aggrieved, the frustrated

author complained and promptly found his manuscript returned, along with a long

(some say three pages) critique of why the book and its hero, a certain

Inspector Morse, was not a viable publishing opportunity. Mr Dexter is, of

course, far too much of a gentleman to reveal who it was at Collins, back in

1974, who turned down his debut novel. [4]

Retaining the same packaging, Colin

promptly sent the manuscript to another publisher, Macmillan’s, then in the

process of creating a crime list to rival that of Collins and Victor Gollancz.

Within 24 hours (according to some versions of the legend, but certainly with

commendable promptitude), he received a phone call from editor George (later

Lord) Hardinge and the rest, as they say, is history.

2.

Colin

Dexter was born in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in 1930, which makes him a “yellow

belly” (a Lincolnshire term of endearment I believe) and, he would say,

possibly the third most famous person from that county after Nicholas Parsons

and Hereward the Wake. He naturally discounted Margaret Thatcher!

Although he has been closely associated

with Oxford (and some would say directly responsible for the unusually high

mortality rate there), he is, as one might have guessed, a Cambridge man,

graduating in classics from Christ’s College in 1953. His early career was as a

classics master, teaching Latin and Greek, but plagued with ill-health and

persistent deafness, he switched jobs to take up a post in Oxford in 1966 at

the University Examination Board, where he continued to work until retiring in

1988.

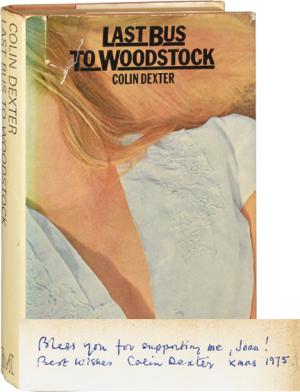

Last Bus To Woodstock was published in 1975

and amazingly (now) it was overlooked in the Crime Writers’ Association’s

awards, the Dagger for best debut novel going to Sara George for Acid Drops.

Even more amazingly, looking back, is the fact that 1,265 copies of that

hardback first edition were remainder just before the book appeared in

paperback in 1977. Colin was offered them, by Macmillan’s, “if he slipped the

van driver a fiver” but turned down the offer due to lack of bookshelf space.

In 2006, a first edition was offered for sale by Blackwell’s of Oxford, priced

£1,500, leaving Colin, as the Americans would say, “to do the Math”. [5] (Ten

years on, a first edition is likely to cost £2,300.)

Last Bus To Woodstock was published in 1975

and amazingly (now) it was overlooked in the Crime Writers’ Association’s

awards, the Dagger for best debut novel going to Sara George for Acid Drops.

Even more amazingly, looking back, is the fact that 1,265 copies of that

hardback first edition were remainder just before the book appeared in

paperback in 1977. Colin was offered them, by Macmillan’s, “if he slipped the

van driver a fiver” but turned down the offer due to lack of bookshelf space.

In 2006, a first edition was offered for sale by Blackwell’s of Oxford, priced

£1,500, leaving Colin, as the Americans would say, “to do the Math”. [5] (Ten

years on, a first edition is likely to cost £2,300.)

More novels followed and, in 1979, his

first CWA Silver Dagger for Service of All the Dead and then, after seven books,

television sat up and took notice.

The television version of “Inspector

Morse” was determined to break various moulds from the off. Each episode was to

be two hours long (then longer than most feature films) and it was to star John

Thaw, up until then known best for a series of tough, no-nonsense portrayals of

coppers from the “shoot-em-up” school, notably in Redcap and The Sweeney.

Thaw, an accomplished stage actor, was said

not to have liked the charact er of Morse at all on first reading, though he was

intrigued by Morse’s love of music (which he shared) and no doubt curious about

his love of real ale (which he hated) and crossword puzzles (at which he was

rubbish!). He was also not the first choice to play the character as far as the

top level of television executives were concerned [6]. But

what did they know?

er of Morse at all on first reading, though he was

intrigued by Morse’s love of music (which he shared) and no doubt curious about

his love of real ale (which he hated) and crossword puzzles (at which he was

rubbish!). He was also not the first choice to play the character as far as the

top level of television executives were concerned [6]. But

what did they know?

Inspector Morse was to become a National

Treasure, celebrated on postage stamps, on tourist trails and, fittingly, as

the answer to a clue in the Times crossword. Worldwide sales of the entire

series (which runs for over 56 hours) are estimated to have reached an audience

of possibly one billion over 200 countries.

When the final episode, showing the death

of Morse, The Remorseful Day was broadcast, it attracted an audience of 18

millions in the UK. Truly, a nation mourned.

3.

However,

I come not to index Caesar but to praise him.

I first met Colin in 1989 at the CWA Awards

ceremony after my second crime novel, Angel Touch, had won the Last Laugh Award

for comedy and Colin’s The Wench Is Dead had won him his first Gold Dagger.

Fortunately I had reviewed (favourably) his

novel for the Sunday Telegraph and it remains one of my favourites, so much so

that in the programme for Bouchercon 26 in Nottingham in 1995, I concocted a

light-hearted parody which included a police report containing his wife

Dorothy’s maiden name, his birthday and the home telephone number of his then

editor Maria Rejt. Perhaps three people in the world got the joke, but as long

as one of them was Colin, I was happy.

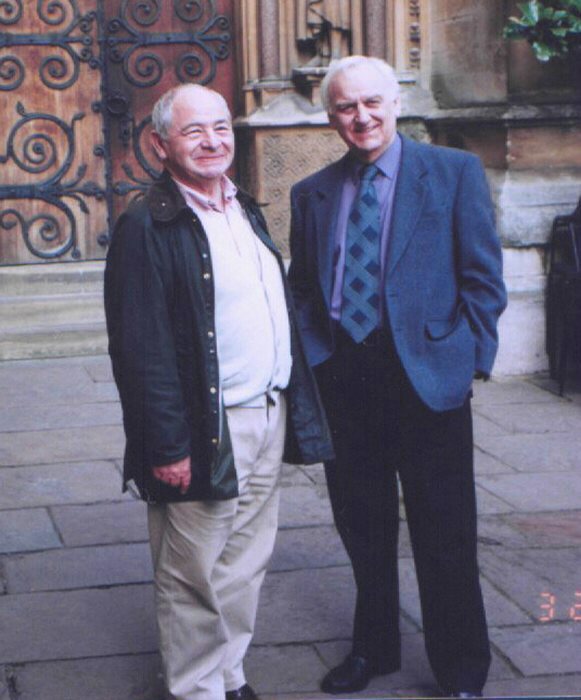

We really got to know each other during the

1990 Bouchercon, the first to be held in London, where I still had a day job in

the brewing industry. As this was possibly the only convention of crime writers

and fans ever to be organised at a university venue which did not have a bar, I

took the initiative and produced (on one sheet of A4) a list of the locations

of the nearest pubs to the Aldwych, leaving copies at the convention reception

for thirsty arrivals.

Only a handful of these free “Angel” pub

guides were circulated before the Bouchercon organisers confiscated them (!)

but one did find its way into the hands of Hilary Hale, then the out-going

crime editor at Macmillan’s, shortly to take up a new post at Little, Brown.

She sought me out and asked for advice on which nearby pub served the best beer

as she wanted to take Colin Dexter for a drink.

I suggested a Bass pub on the corner of the

Aldwych and wangled myself an invitation. I vaguely remember it being a

splendidly convivial evening and word soon spread so that the pub quickly

filled with Dexter fans and weary American conventioneers exhausted by trying

to find the non-existent bars at the Bouchercon.

That was the start of the beer-based side

of our friendship, which over the years saw Colin become a regular guest at the

Campaign for Real Ale’s Good Beer Festival and a judge for the annual British

Guild of Beer Writers’ Awards, a position he took very seriously, as pictured

here in 1991 with myself and fellow judges Robert Humphreys (of Bass) and David

Young (The Times).

Even at designated literary events, we

always seemed to find time for a beer. At a Shots On The Page convention in

Nottingham, I arranged for Colin to pull the ceremonial first pint to mark the

opening of a newly refurbished Home Brewery pub, and on one infamous occasion

we were both guests of honour at a Boardroom luncheon in the King & Barnes

brewery in Horsham in Sussex.

One of the earliest non-beer related events

we took part in was to talk to a conference of London librarians in 1992 and

part of our brief was to introduce a new, fledgling crime writer, Minette

Walters, whose first novel The Ice House had just appeared. Minette was to

become a firm friend to both of us although that particular terrible

triumvirate sadly never appeared together on stage again.

Colin was not only good company in private,

over a pint of ale. In public he was a wonderfully warm, self-effacing speaker

who charmed an audience with his natural wit and erudition, dealing politely

with even the most inane questions he had been asked many, many times

previously.

He had a fund of anecdotes and stories

which gave the unwary listener the impression that he was just a simple man of

simple pleasures (doing the crossword, visiting the Garden Centre at week-ends,

listening to The Archers) for whom this whole ‘bestselling author’ thing all

been a bit of a surprise.

I had the pleasure of doing a Desert Island

Hell interview with him at the British Film Institute, where I stranded him on

a mythical desert island with only the books, music, politicians, etc. which

would drive him mad. Not surprisingly, having only the Daily Mail as a newspaper

was high on his hate list, but he also volunteered Dorothy L. Sayers as the

crime-writer whose books would drive him bonkers ‘as she was such a snob’.

In 2007 I produced ‘An Evening With…’ both

Colin and Ted Childs, the producer of the Morse television series for the Essex

Book Festival, which sold out the City Theatre in Chelmsford within twenty-four

hours. The evening was notable for the long, deathly pause which followed the

inevitable question from the audience: why he had “killed off” his hero?

“I did not kill Morse!” thundered the

outraged author. “He died of natural causes.”

Listening to him speak, an unwitting

audience could be forgiven for not realising that this was the same man who

generated 1,230.000 hits when his name was Googled (as opposed to 970,000 hits

for “Inspector Morse”), even though he had have absolutely no idea of what

being Googled involved, this was a man who used words like boustrophedon[7] in a

modern detective story (along with an estimated 11,500 other words in a vocabulary roughly 38 times bigger than

that of a tabloid newspaper); who claims his favourite writer is Tacitus[8] (he

approves of the short, precise sentences), and who had pioneered the use of

“the Oxford comma” in modern grammar.

He was always an advocate of the poetry of

A.E. Houseman but was less well-known for his championing of the work of Lilian

Cooper (1904-1981) from whom he borrowed the title of one of his novels:

Espied

the god with gloomy soul

The

prize that in the casket lay,

Who

came with silent tread and stole

The

jewel that was ours away.

Whilst signing my copy of The Jewel That Was

Ours in 1991 when we were both guests of the King & Barnes brewery in

Horsham, he confided, with a mischievous chuckle, that ‘Lilian Cooper’ was not

in fact a published poet, but his late mother-in-law.

And when he and I did another “Evening

With…” event in 2010 to raise funds for the Lavenham Literary Festival in

Suffolk, he also revealed that his German teacher at school had been none other

than Gerard Hoffnung, the master of the droll delivery style which Colin had

perfected.

Colin has also, famously, appeared

Hitchcock-like in virtually every episode of Inspector Morse, though it did

take him until 1993 to get a speaking part and there is supposedly one famous

episode from which he is missing after his scene was mistakenly left on the

cutting-room floor! He continued the tradition in the ‘prequel’ series Endeavour.

His involvement in the TV adaptations

brought him into contact with virtually the entire British acting establishment

from Sir John Gielgud to the crime-writing actor Martyn Waites (who played the

Duty Constable in the episode Dead On Time) not to mention debutantes Liz

Hurley and Rachel Weitz, at least two Dr Who’s and half the regular cast of the

Harry Potter movies.

Yet none of these brushes with celebrity

seem to have turned his head. He is still someone who will politely direct a

lost stranger to the railway station, sign an autograph (always legible, always

personalised) and will always buy the first round. (Though he never forgot

those who avoided buying a round!)

He was also just about the only crime

writer I know who has never bitched or complained about television adaptations

of his work. He once told me that his philosophy was: “Books is books, telly is

telly.” Only he probably put it more grammatically than that.

Fame and fortune seemed not to have affect

him.

In short, he was a really good bloke.

4.

But

then I would say that, wouldn’t I? Because I think of him as a dear friend.

What larks we have had over the years and

not just in pubs.

Ironically,

after the last Morse novel appeared in 1999, Colin was busier than ever,

constantly in demand as guest speaker and acting as his own secretary answering

piles of fan mail.

He still found time for his friends,

though, as I can testify.

In 2002 I embarked on a historical thriller

set in 1st century AD Roman Britain. By post and telephone, Colin

coached me until I managed to remember a few scraps of the Latin I had learned

at school, even teaching me Roman military obscenities which I had not

encountered thus far in my career as an archaeologist.

When, in early 2003, I suffered a

paralysing stroke, Colin’s message to the hospital was not only one of the

first but possibly the most memorable: “Tell Mike that if I was a religious

man, I’d be praying for him; but I’m not, so I won’t be.”

Released from hospital, I determined to

finish the book and once again Colin helped to re-teach me the Latin I had forgotten

thanks to the stroke and when Boudica and the Lost Roman finally appeared in

September 2005, I was able to give him one as a birthday present. He professed

to approve of it, despite the fact that one of his Latin jokes had been cut by

an unthinking copy editor, something he never allowed me to forget, and even

wrote a glowing review of it for the Birmingham Post – a hand-written review,

which the newspaper stupidly threw away after publication!

Contrary to popular opinion, though, he

did not let me into his greatest secret, that of the missing Christian name

beginning with ‘E’ – something which kept the nation guessing for 13 years.

Although he was genuinely delighted that my wife guessed the Quaker connection

about two days before the book revealing it was published.

Epilogue

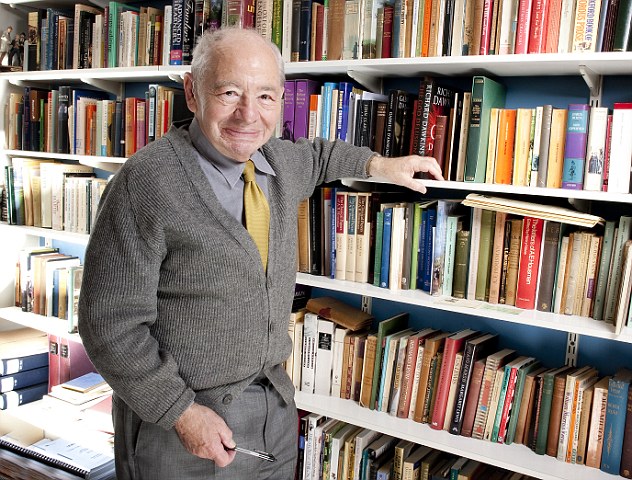

On

a birthday visit to Oxford in 2007, my wife and I stopped in for tea at Colin

and Dorothy’s home and they allowed me to take an ‘official’ 77th

birthday portrait.

He was on fine form and seemed in no danger

of slowing down, his conversation bouncing from demanding news of fellow crime

writers, explaining, very patiently, some new crossword clues he had devised

(including some rather rude ones) and taking a generous interest in my own

health and writing career.

His own health, however, was always

problematic and his long-term hereditary deafness a constant source of

frustration. Although he had long ago given up smoking, and more recently

alcohol, he told me that if some higher power (he did not specify a God) told

him he was definitely going to die tomorrow, he would ‘send for a packet of

Benson & Hedges immediately’.

One of his last public appearances over in

East Anglia, where he usually visited my wife and I, was to celebrate the new

Visual Arts Centre complex in Colchester in 2012. Visibly frail, my wife and I

acted as his assistants, helping him on to and off stage. Once ensconced there,

he had, as usual, the capacity audience in the palm of his hands.

I have so many fond memories of Colin that

it is hard to pick out one above the rest, though I always treasure the splendid

quote he provided for my “Angel” series of novels: The outrageous, rip-roarious

Mr Ripley is an abiding delight.

He followed this up with a note which read:

“If anyone tells you that ‘rip-roarious’ is not a word, tell them Colin Dexter

says it is now.”

I have, Colin, and will continue to do so.

NOTES:

[1] (Latin) “Mess mate” or old

army pal.

[2] COLIN (L=left with ‘coin’

(penny) around it. DEXTER is Latin for ‘right’.

[3] It was a “Miss Silver” story

by Patricia Wentworth.

[4] It was Elizabeth Walter,

the editor who discovered Lovejoy, and Angel!

[6] The late Ian Richardson was

a front-runner.

[7] Meaning to sweep from side

to side. From the Greek, bou-strophous

meaning “ox-turning” (as when ploughing).

[8] Publius Cornelius Tactitus, Roman historian (AD 56 to 120)

naltrexone off label uses

read low dose naltrexone reviews

low dose naltrexone allergies

charamin.jp naltrexone 50 mg tablet