Author Michael Kurland is best known for writing both detective and science fiction novels. He has edited three themed anthologies of Sherlock Holmes short stories, My Sherlock Holmes (stories narrated by characters other than Watson or Holmes), Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Years (stories set during the period in which Holmes was supposed to be dead) and Sherlock Holmes: the American Years

Author Michael Kurland is best known for writing both detective and science fiction novels. He has edited three themed anthologies of Sherlock Holmes short stories, My Sherlock Holmes (stories narrated by characters other than Watson or Holmes), Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Years (stories set during the period in which Holmes was supposed to be dead) and Sherlock Holmes: the American Years

(stories set in the time between Holmes' graduation from university and his meeting Dr. Watson. His novels The Plague of Spies and The Infernal Devices were nominated for an Edgar Award for Best paperback Original Mystery in 1970 and 1980 respectively.

There’s a joke they tell about a man running into his friend in the lobby of the old New York Daily Mirror. “Frank,” the man says, “what are you doing here?”

“I work here,” Frank replies furtively. “I’m a reporter on the city desk. But for god’s sake don’t tell my mother! She thinks I play piano in a whorehouse.” Well, my mother never would have believed that; she knew I can’t play the piano. And she knew I was going to be a writer because I told her so when I was ten years old. I would write humorous essays like Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker, create clever bon mots like Noel Coward or Oscar Levant, examine slices of life like Damon Runyan or F Scott Fitzgerald, take my readers to worlds beyond the stars, like Edgar Rice Burroughs and E. E. Smith. Many of these writers flourished a full generation before I was born, but what was that to me? was born, but what was that to me?

At fourteen I discovered mystery stories and couldn’t decide whether I was Rex Stout, Dorothy Sayers or Dashiel Hammett. Or maybe Simon Templar. Not Leslie Charteris, but Simon Templar. How debonaire, how quick-witted, how good looking.

I was 21 when I got out of the Army, enrolled at Columbia University and began hanging out in Greenwich Village. There I fell into bad company: Randall Garrett, Phil Klass (William Tenn), Don Westlake, Harlan Ellison, Bob Silverberg, and assorted other sf and mystery writers. This was my downfall, the start of my slide into genre fiction. I wrote a science fiction novel, Ten Years to Doomsday, with Chester Anderson, a brilliant poet and prose stylist who taught me much of what I know about writing, and followed that up with The Unicorn Girl, a seque

l to Chester’s The Butterfly Kid, a pair of fantasy novels in which the two main characters were ourselves, Chester Anderson and Michael Kurland. These books, and The Probability Pad, a continuation written by my buddy Tom Waters, have become cult classics, known collectively as the Greenwich Village Trilogy, or sometimes The Buttercorn Pad.

For most of the next decade I wrote science fiction, mostly humorous (or at least I thought so) adventure stories. Then my agent asked me if I’d like to do a Sherlock Holmes story, as a paperback house wanted a possible series and thought they could get the rights. I considered. No, I decided. But it might be fun to do a Moriarty story. So I wrote a portion and outline. At this moment a major packager named Bernard Geiss needed someone to ghostwrite an autobiography for some film star. My agent suggested me. “Let’s see some of his stuff,” said Bernie. The agent sent along the P&O for the Moriarty book. I was called in to meet Bernie. There was a fireman’s pole in his office leading to the floor below. “Whee!” I said, “A fireman’s pole!” and I promptly slid down it. This clinched the deal for Bernie. He used the pole as some sort of judge of character, asking new authors to slide down it at the end of the interview. And here I’d done it unbidden. Also, as he told me when he took me out to lunch that day, I was the finest prose stylist he’d ever read (his words not mine). “But you realize,” he added, “that’s not worth a dime.”

So he bade me forget about the autobiography and write the Moriarty book for him. And he waved a contract at me. Dividing the word length he wanted against the advance he offered I realized I’d be getting about fifty cents a word. Wow! And suddenly I couldn’t write a word. I would type, say, “the professor,” and stop. Were those two words worth a dollar? Was “the” worth fifty cents? I got over this when I read an article about Las Vegas by Tom Wolfe in Esquire. It began “Hernia, hernia, hernia...” and so on for about 200 words. Now Esquire paid at least fifty cents a word, so if Wolfe could make a hundred dollars by repeating the same word over and over, I could surely write, “The professor...”

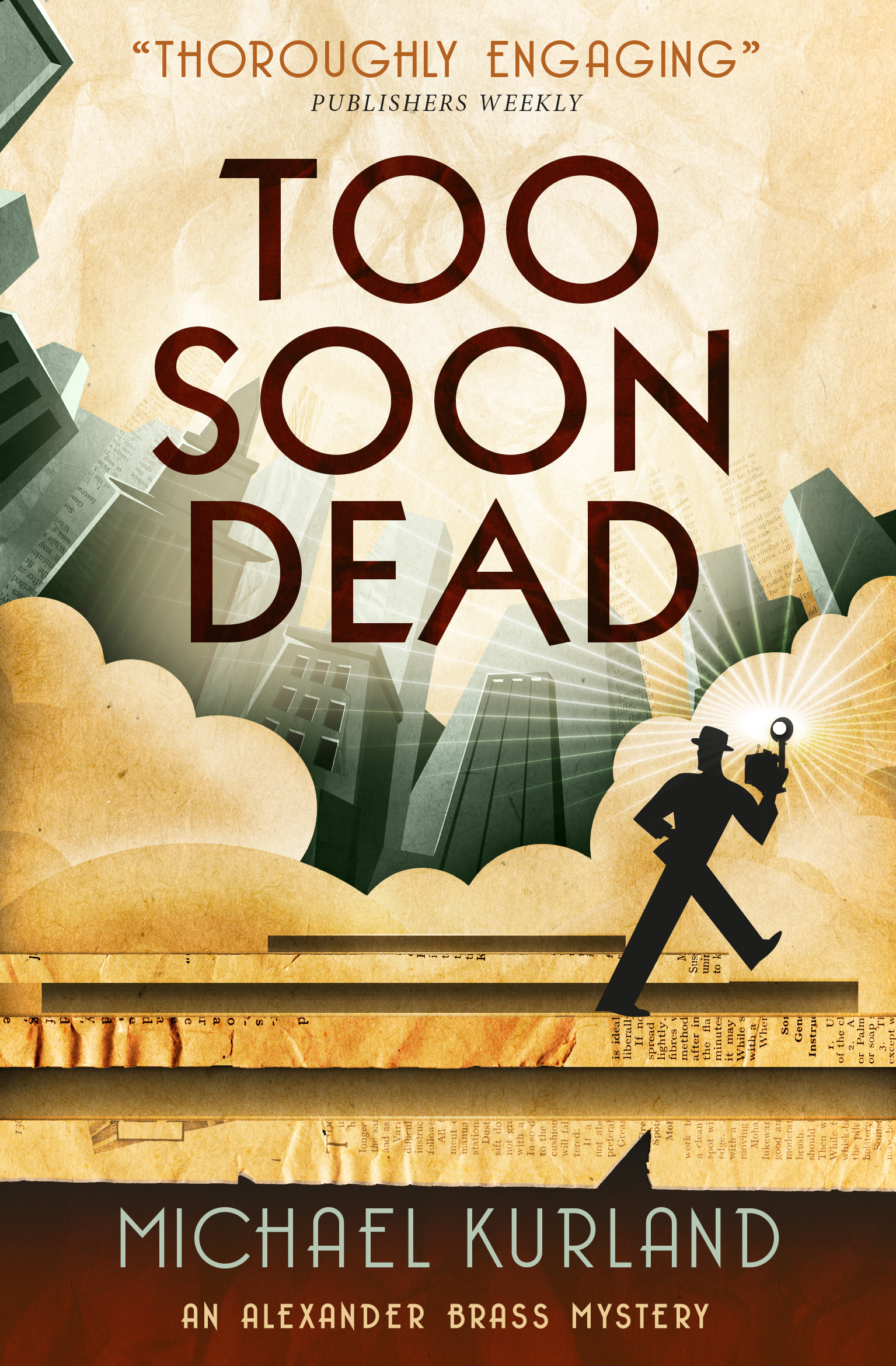

All this time another character from another period was taking shape in my mind, one who was wholly mine and owed nothing to the Sherlock Holmes oeuvre (grateful as I am to Dr. Doyle and the immortal character he created). Introduced in Too Soon Dead, he is Alexander Brass, columnist for the New York World in the years between the two world wars, when booze was suddenly legal again but the Great Depression was abroad in the land. It was a time when, as Brass’s assistant Morgan DeWitt put it in the second book in the series, The Girls in the High-Heeled Shoes, “An employer still doesn’t have to advertise a job. He just has to go into a dark corner, make sure there is nobody in earshot, and whisper quietly up his sleeve, ‘I need someone to sweep the floor and lift heavy objects. I can pay ten dollars a week’. Before he can make it to the front door, four hundred people will be lined up outside, politely, quietly, hopefully.”

All this time another character from another period was taking shape in my mind, one who was wholly mine and owed nothing to the Sherlock Holmes oeuvre (grateful as I am to Dr. Doyle and the immortal character he created). Introduced in Too Soon Dead, he is Alexander Brass, columnist for the New York World in the years between the two world wars, when booze was suddenly legal again but the Great Depression was abroad in the land. It was a time when, as Brass’s assistant Morgan DeWitt put it in the second book in the series, The Girls in the High-Heeled Shoes, “An employer still doesn’t have to advertise a job. He just has to go into a dark corner, make sure there is nobody in earshot, and whisper quietly up his sleeve, ‘I need someone to sweep the floor and lift heavy objects. I can pay ten dollars a week’. Before he can make it to the front door, four hundred people will be lined up outside, politely, quietly, hopefully.”

It was, as another writer has put it, the best of times, it was the worst of times. And New York City was the Center of the World. The New Yorker was the cleverest magazine The New York Times was the king of newspapers, the Broadway shows were written by George and Ira Gershwin and Cole Porter, and everybody who could do anything better than anyone else moved to New York. And still the poor lived among the rich and gangsters flourished, having moved from booze to other enterprises. Gambling and prostitution, sure, but if a hotel or restaurant wanted to get its laundry done, the mob took a bite. Mozzarella for god’s sake cheese was controlled by the mob. And the European dictators had started poking their noses across the ocean, with the German-American Bund and the America First party.

What a mix! What a period to write about. What a time for Alexander Brass and Morgan De Witt to live. And I am pleased to have given them life.

Check out Shots’ review of TOO SOON DEAD here.

Published by Titan Books Pbk £7.99 November 17, 2015

temovate tube

link furosemide 40mg

discount coupons for cialis

read cialis discounts coupons

free printable viagra coupons

open free discount prescription card

abortion at 10 weeks

open abortion papers

discount prescriptions coupons

site discount card for prescription drugs

manufacturer coupons for prescription drugs

outbackuav.com cialis coupons and discounts

naprosyn 750 mg

open naprosyn jel nedir

cialis.com coupons

achrom.be cialis discount coupons online

naltrexone and alcohol

site naltrexone pregnancy