When researching my debut novel Plague Land, set in the aftermath of the Black Death of 1348-50, I was looking for ways to connect with the people of medieval England. I don’t always like the idea that the past is a foreign country – these people were the same species as me, with all the same desires and urges. I only had to re-read the Canterbury Tales to see they were ambitious, envious, kind, skeptical, lusting…. they even laughed at same sort of crude humour that I shouldn’t admit to finding funny. If I were transported into this past, I think I would fit in fairly easily – except perhaps in one key area. My attitudes to death and the existence of an afterlife.

When researching my debut novel Plague Land, set in the aftermath of the Black Death of 1348-50, I was looking for ways to connect with the people of medieval England. I don’t always like the idea that the past is a foreign country – these people were the same species as me, with all the same desires and urges. I only had to re-read the Canterbury Tales to see they were ambitious, envious, kind, skeptical, lusting…. they even laughed at same sort of crude humour that I shouldn’t admit to finding funny. If I were transported into this past, I think I would fit in fairly easily – except perhaps in one key area. My attitudes to death and the existence of an afterlife.

Let’s start with death. In the medieval world, death wasn’t quite the pariah of our times. Instead it was A list, turning up everywhere from the doom paintings on the church walls and margins of illustrated manuscripts, to the stories and the poetry of the times. A favourite tale was the ‘Three Living, Three Dead.’ Three arrogant young noblemen meet three corpses in various stages of putrefaction. Forget the luxuries and the pleasures of this Earth, the corpses tell the young men. Focus instead upon your soul and the afterlife. For death awaits, and it’s coming sooner than you think.

The afterlife was a real place to these people – with Hell just pushing Heaven from the spotlight, with its demons, fires and melting pots of boiling sinners. But our society has forgotten about Hell, and, in a way I think we would quite like to forget about death as well – at least its reality. When a loved one dies, we often feel affronted that such a thing could happen. We have certain words to soften its blow – the person ‘passed away’ or even ‘passed.’ I have a friend, a GP, and he can be besieged by the relatives of a dying person, not able to accept that their loved one will die, not even when the prognosis is hopeless.

But this is the paradox. We may not like death on intimate terms – but we couldn’t be fonder of it at the vicarious level. We read about it all the time. In newspapers and books. Or we watch TV shows and films or play computer games that revolve about the subject. Some of us even write novels about it. But it’s not quite the same variety of death as in the Middle Ages – this is one-step removed death. I once berated my teenage son about his particularly gruesome Playstation game. I was worried that the violence was warping his mind. ‘What if those were real people?’ I said, as his character ran through a battlefield and brutally gunned down enemy soldiers at every opportunity. ‘How would you feel then?’ He looked up momentarily and addressed me as if I were mad. ‘It’s made-up Mum.’ Sometimes I wonder if this is how we think about death…. it’s made up.

Okay, I hear some of you saying – I know what death is like. My mother, father, husband, son or daughter died. Please don’t think I’m trying to demean your grief. I’ve experienced it myself. But imagine this. You live in the Middle Ages. You’re a parent, and two out of your six children die before they are five. Or you’re a husband, and both your first and second wives die in childbirth. You go into the street and seen a felon being hung from the gallows, or perhaps even drawn and quartered before this last act of punishment. Or you’re unlucky enough to live in a cramped and squalid street when the Black Death hits town. You must stay within the same four walls and watch most of your family die a horribly painful death. You even carry their dead bodies to the pit yourself.

Sometimes I wonder how our ancestors coped with this variety of death and its constant onslaught. There’s no doubt that the idea of an afterlife was a comfort, and perhaps, like anything that you experience over and over again, in the end, you just become accustomed to it?

But we’re not so accepting of death, are we? And certainly not an untimely one. We have a thing called lifespan. We expect to live three score years and ten. Most of us do – if not longer. We have food, shelter and access to medicine. Above this, we have dreams and ambitions. We get to learn, travel, and to experience the world. By the time we shuffle off this mortal coil, we might have had enough of living anyway – so perhaps the prospect of an afterlife loses some of its appeal? A Jehovah’s witness once asked me ‘don’t you want to live forever?’ My answer was no – but that might be because I’m envisaging my own death at the end of a long and fulfilled life?

In the past however, death could come at any time. It often took the youngest, strongest and most talented. It was random and meaningless, and could not be ignored. It happened in your house, your street, and it happened to you. No wonder death was so celebrated. It was the great leveler, waiting to judge each person. Young or old. Rich or poor. Heaven or Hell. It was a beginning, not an end.

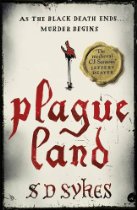

Hodder Paperbacks (21 May 2015) £7.99

Buy it

HEREdiscount prescription

go walgreen online coupons

walgreens pharmacy coupons new prescription

read coupon pharmacy

temovate tube

link furosemide 40mg

tretinoin 0.025%

open ventolin pill

forms of abortion

site coupons promo codes

discount coupons for cialis

read cialis discounts coupons

abortion pill costs

fyter.cn walk in abortion clinics

seroquel 300

link seroquel 300

ventolin prospecto

click ventolini cali

naltrexone implant australia

go who can prescribe naltrexone

low dose naltrexone allergies

charamin.jp naltrexone 50 mg tablet