Some crime stories stretch credibility just a bit too far. For example there was the story of the schooner Jane, outward bound from Gibraltar to Salvador. According to the tale, it was in the summer of 1821 and Jane had a cargo of olives, oil and beeswax, plus an intriguing and unexplained thirty eight thousand Spanish dollars, better known as pieces of eight.

Some crime stories stretch credibility just a bit too far. For example there was the story of the schooner Jane, outward bound from Gibraltar to Salvador. According to the tale, it was in the summer of 1821 and Jane had a cargo of olives, oil and beeswax, plus an intriguing and unexplained thirty eight thousand Spanish dollars, better known as pieces of eight.

The voyage began well, as Jane sailed with a small crew on a summer calm sea, but the temptation of silver riches proved too much for some of the hands. It is well said that ship’s crews never mutinied while sailing round the Horn, but an easy voyage, or loitering in the Doldrums, created a climate of boredom that encouraged disgruntlement. The combination of waiting wealth and no hard work proved fatal.

Two of the crew attacked the captain and threw him, still alive, overboard, then trapped another two men in the hold and tried to suffocate them. After a day or so, the mutineers relented and allowed the suffering two on deck, toyed with the idea of tossing them overboard in the captain’s wake, but decided to let them live. Instead of murdering them, the mutineers invited them to share the spoils.

So far, the story is bloody but believable. The incredible part starts now. The mutineers had tasted success; they had a sound vessel and tens of thousands of silver dollars with the entire world before them. Nobody knew where they were or who they were, but rather than run for some exotic port where they could live a life of luxury, they decided to go to . . . the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Why?

Why go to a place where they were bound to be immediately identified as outsiders, with a climate that is at best bracing and at worst downright hideous?

Not only that, but they left a trail behind them. They bought a small boat in the island of Barra, were seen by a customs cruiser in the Minch, scuttled the schooner, landed in Lewis and buried the silver on a Hebridean beach.

Why?

There is no logic in this story. Why would anybody do that?

The most unbelievable part of the whole story is this: every word was true. That is what is strange about the historical reality of crime; it is utterly unpredictable.

Novelists work logic into their stories and try to create neat patterns of motive and opportunity in colourful murders and intricate robberies, but reality is not always so easily ordered. Fact can be much stranger than fiction, with the rule of coincidence ready to thrust a jagged spoke into the oiled wheels of even the best laid plans of mouse-like men.

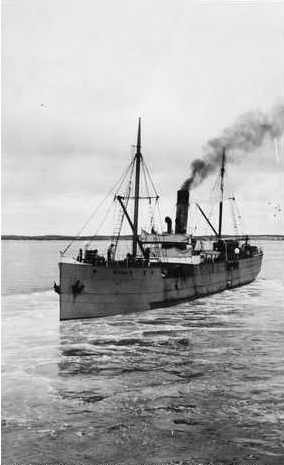

For example, when a group of thieves stole an entire ship from Glasgow in 1880, who would have known the crime would be solved by a homesick Glasgow policeman thousands of miles away? The ship was Ferret and she was central to an amazingly complicated scam that included changing her name, creating alibis for the entire crew, altering the ship’s appearance and blagging their way across half the world. However nobody reckoned with the home-sickness of Constable James Davidson. A man from the Clyde, he missed his Scottish home so much that he read the Glasgow papers. In one of these he found a description of the stolen ship Ferret.

For example, when a group of thieves stole an entire ship from Glasgow in 1880, who would have known the crime would be solved by a homesick Glasgow policeman thousands of miles away? The ship was Ferret and she was central to an amazingly complicated scam that included changing her name, creating alibis for the entire crew, altering the ship’s appearance and blagging their way across half the world. However nobody reckoned with the home-sickness of Constable James Davidson. A man from the Clyde, he missed his Scottish home so much that he read the Glasgow papers. In one of these he found a description of the stolen ship Ferret.

Quite by chance, Davidson was looking over the various vessels anchored in Hobson’s Bay, off Melbourne, and he noticed one that looked very like Ferret. He checked her name, discovered she was not registered and alerted his superiors. Within no time a party of Royal Marines boarded her. After that it was all downhill for the master and crew of the Ferret. A fiction writer would shudder to solve a crime with such a coincidence, but fact does not have to take into account the cynicism of a readership experienced in crime fiction.

However, most genuine crime would be too mundane to fit into the pages of a fiction book. The majority of murders are brutal but uninteresting to anybody apart from the participants and their close family. One brawl between a bunch of drunks is much like another and most thefts were petty, opportunistic and often pointless. After spending thousands of hours poring over the crimes of the nineteenth century, I have come to the conclusion that the majority of criminals were inefficient rather than interesting and crimes were more sordid than stimulating.

When writing any book on true crime, I had to trawl through innumerable cases, police court, high court, sheriff court . . . not to mention newspaper reports. The vast majority of cases were tedious, laced with some of incredible sadness. The majority of murders were between people who knew each other well, spouses, family members or friends, with killings by strangers rare. Some were incredibly sad, as when a depressed mother murdered her new-born baby.

After a few days or weeks of research, constant reading of crime becomes less interesting and the facts merge into a meaningless mass of statistics and names. It was difficult to relate the cases with real people, to put hearts and souls and thoughts and dreams into the vast numbers of cases of theft and drunkenness and petty assault.

Then out of the sordid morass something would leap out, something unique or original or startling in its scope. For instance there was a professional criminal named James Mackoull who was involved in numberless crimes including the murder of William Begbie, an Edinburgh bank messenger. Or a slighted wife throwing vitriol in the face of her mother in law. Or Henry Saunders who spent months in an intricate plan to rob the Greenock Bank. Or. . . . Once one was found, other cases seemed to clamour for attention, long forgotten crimes screaming to be allowed to be read, or well remembered and recounted cases demanding another airing so the reader can decide if a hanging was justified or if the memory of an innocent man has been tarnished for many decades. Sometimes it seemed unfair to leave somebody out, and at other times the research uncovered an area of crime that was entirely new to me.

For instance I had no idea of the violence that accompanied the early Cotton Spinners Combination – the union – in Scotland or of the near commando tactics of the Glasgow police as they raided their head quarters in the Black Boy Tavern. I was amazed at the callousness of Willie McLean, who may have a claim to fame as one of Scotland’s earliest hit men. He joked about shooting his victims and thought little of the misery he caused. I had no idea that the victor of Scotland’s last duel, in Cardenden in Fife, was tried for murder. I had no idea that the break in at Dundee’s museum in 1875 led to the dismissal of the chief constable, or that the railway navigators caused mayhem throughout the country.

Crime was widespread and could be terrifying. There was no corner of the country that escaped, from the outermost isles to the darkest alleyway in the densest city. It could be sordid, ugly, sad and cruel but also, for those who look, it can offer endless fascination, and it is that last quality that the fiction writers tap into when they weave their web over their readers. Without the reality, there could be no fiction, and if one is stranger than the other, and then both have a disturbing seduction that may involve the people who live on the other side of the law.

Just be thankful that there is a blue line of police between them and us.

Bloody Scotland: Crime in 19th Century Scotland, by Malcolm Archibald will be available online and in bookstores from 16th September.

For more information, go to www.blackandwhitepublishing.com

ISBN: 9781845027896, £9.99 PB

website

website women who cheat on husbands

read

go which is better chalis or viagra

i need to cheat on my girlfriend

go i cheated on my girlfriend and i want her back

my husband cheated again

click my husband cheats

wife adult stories

go adult stories choose your own adventure

walgreens pharmacy coupons new prescription

read coupon pharmacy

can i take amitriptyline with hydrocodone

link can i take amitriptyline with hydrocodone

bystolic coupon mckesson

site forest laboratories patient assistance

cialis.com coupon

go free discount prescription card

ventolin prospecto

click ventolini cali

grocery discount coupons

link define abortion

dexamethasone suppression test

web-dev.dk dexamethasone mechanism of action in cancer

clomid proviron

clomid clomid testosterone