|

Bridget O’Donnell is a former BBC producer. She has written for various newspapers including the Guardian and recently completed with distinction an MA in Creative Non-Fiction at City University. She lives in London with her family. Inspector Minahan Makes a Stand is her first book.

|

One evening in September 1879, John Sallecartes spotted a nineteen-year-old girl named Adelene Tanner walking along the Tottenham Court Road. Artless, vulnerable and alone, she was just the kind of girl he was looking for. Sallecartes started to walk beside her down the street. He was attentive, charming and took an interest in her. He steered her to a café in Soho, where he introduced her to his accomplice: a ‘stylish’ Frenchman named Edouard Roger. These two middle-aged men then insisted Adelene have a glass of wine with them and proceeded to ply her with drink until she ‘scarcely remembered what she said’. Later in the evening, Sallecartes told Adelene that Roger had taken ‘a great fancy to her; that he would take her to Paris, and if she would like to be his wife, he would marry her’. Naively, Adelene agreed to go.

This was John Sallecartes’ job. He was an international trafficker. He picked up girls in London and enticed them into travelling across the Channel with him. Once overseas, he sold his ‘packages’ into French and Belgian brothels, where, trapped by keepers and without money or friends, they were coerced into having sex with clients. Edouard Roger ran a high-class brothel in Brussels. He paid Sallecartes 300 francs for Adelene.

A man of Sallecartes’ experience knew exactly how to appeal to guileless girls, as he later explained to a journalist:

You get the girl to listen to you, and persuade her to anything. [That] they will have good situations, fine clothes and all the inducements which would enable a sharp girl to smell a rat. But they swallow the bait like gudgeons.

This Victorian trafficker was in the same industry then as the gangs of men recently prosecuted in Rochdale and Oxford are now: the business of grooming girls for the purposes of sexual exploitation. Just like Adelene, today’s victims are deliberately given drink and drugs, courted and deceived, then moved from man to man and eventually ‘trafficked’ from city to city. Hence the crime’s other name, ‘internal trafficking’.

I first learned of this crime while working as a producer on the BBC’s Crimewatch programme, and was shocked to find that modern, educated British girls could still fall into the trafficker’s trap. But it quickly became clear that adolescents everywhere remain vulnerable to the approaches of unscrupulous older men: from celebrities like Jimmy Savile to ordinary strangers. When trying to find out why, I discovered that the late-Victorians had grappled with exactly the same issue, and that one policeman in particular – named Jeremiah Minahan - had risked everything to try and expose the problem. Curious about this Irishman living in London, I began researching Inspector Minahan and the sprawling London underworld that he once policed.

In the early 1880s, the age of consent in England was thirteen. Young prostitutes thronged London’s West End and filled its 6-10,000 ‘disorderly houses’. Policemen like Inspector Minahan had few powers to stop soliciting or intervene against brothel-keepers and, with many politicians counting as clients, calls for a reform of the ineffective vice laws went unheeded. That is, until evidence of an even more desperate trade began to emerge: the trafficking of British girls by gangs of foreign men into brothels abroad.

In July 1882, a Lords’ Select Committee admitted that ‘large numbers’ of girls had for ‘many years’ been groomed in London then sold on the Continent. Their investigation exposed the activities of the gang of traffickers run by John Sallecartes, who had ensnared Adelene Tanner in 1879 and boasted that 250 British girls were sold overseas every year. Some - including Adelene - were rescued by moral campaigners, but they rarely recovered from the trauma of their ordeal. The Victorians called it ‘soul murder’.

One month later, Inspector Minahan encountered yet another trafficker, but this time she was British. Named Mary Jeffries, she was a former prostitute who also ran a brothel in Chelsea. But when Minahan tried to report Jeffries, no action was taken. Why? Firstly, Jeffries sold girls to politicians, peers and even royalty: celebrated men far too powerful to expose. Secondly - as the Victorian journalist William T. Stead wrote - ‘the very horror of the crime was the chief secret of its persistence’. Then as now, the crime was too awful for many to face up to.Ignoring it seemed like an easier option. But in July 1885, William T. Stead decided enough was enough. After reading through the evidence gathered by Minahan about Jeffries and her clients, Stead published a sensational newspaper exposé detailing all London’s hidden sex trade. The resulting public outrage shook Parliament from its lethargy and in August 1885, a range of reforms were passed to curtail trafficking and juvenile prostitution. Most significantly, the age of consent was raised to sixteen, a law that still holds today.

|

|

|

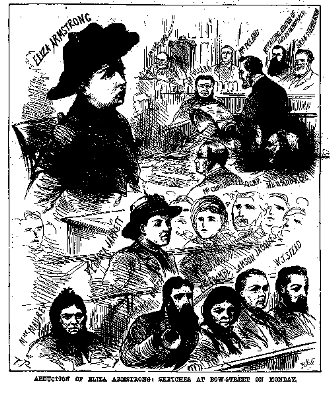

These sketches from 12 September 1885 edition of The Penny Illustrated Paper so brilliantly capture the hubbub of court and the events surrounding Inspector Minahan's investigations used in the endpapers of the book.

|

While working for the BBC I also interviewed some trafficking victims in Thailand. One I particularly remember was a Burmese girl who had been promised a better life overseas and who had wanted to help her family. She was young and naïve and thought she was going to work as a maid, but instead was driven through Thailand and locked in a Bangkok brothel. She did not speak Thai and had no money or friends or family in the country. Her only escape, she told me, was to jump to her death from the roof. She had once stood on that roof for several hours, but could not pluck up the courage. Only when she contracted HIV did the brothel release her. She was a humble, gentle girl who had been horribly exploited and I have never forgotten meeting her, because she too had been the victim of a ‘soul murder’.

Back in the 1880s, Inspector Minahan also met girls like this. He too learned that ignoring these kinds of crimes only helped the girl’s abusers, who would do anything to avoid public exposure. But this did not stop Minahan or his supporters. They went on to change British law and in doing so stopped many more girls (and boys) from becoming victims.

Today we are again being bombarded with reports about traffickers, grooming gangs and lascivious celebrities too powerful to prosecute. And for us too there is the same feeling of ‘horror’ that William T. Stead once described. Yet the Victorians did teach us something: that these revelations, however difficult, are ultimately a positive thing, because only when the silence is broken, do the victims actually have a voice.

More information about Bridget O’Donnell and her work can be found on her website. You can also follow her on Twitter @bodonn

Inspector Minahan Makes a Stand by Bridget O’Donnell

published in paperback by Picador on 20th June 2013. £9.99

buy abortion pill

read abortion pill online purchase

where can i get the abortion pill online

abortion pill buy abortion pills online

cialis free sample coupons

click free prescription drug cards

cialis.com coupons

achrom.be cialis discount coupons online

abortion pill pros and cons

accuton.com abortion pill stories

amoxicillin dermani haqqinda

amoxicillin amoxicillin 500 mg

naltrexone alcohol side effects

click buy naltrexone