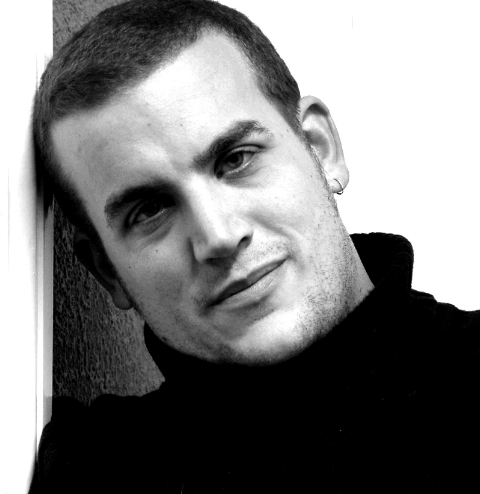

Guy Adams in Shotsmag Ezine

Guy Adams trained and worked as an actor for twelve years before becoming a full-time writer. He is the author of the best-selling Rules of Modern Policing: 1973 Edition, a spoof police manual ‘written by’ DCI Gene Hunt of Life On Mars. Guy has also written a two-volume series companion to the show published by Simon & Schuster; a Torchwood novel, The House That Jack Built (BBC Books); and The Case Notes of Sherlock Holmes, a fictional facsimile of a scrapbook kept by Doctor John Watson. Carlton Books published it in 2009 in association with the Estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the writer’s birth. Now he is back with a new Sherlock Holmes - The Breath of God (Titan Books 2011).

Holmes gets beneath the skin. He attract obsession like few other literary figures.

Before I became a full-time writer I worked as an actor and he had the same power then.

I had been touring the country (or at least the more forgiving parts of it) alongside friend and fellow actor Philip Jarrett. We were trying our hand at comedy with a sketch show that we had written. As long as you could forgive the scant audience and abject penury it was all going rather well. There were no death threats. People laughed. We just about kept ourselves afloat on the road. Subsisting off petrol station sandwiches and water from toilets.

Phil and I had always been fans of Sherlock Holmes, and when working on new material to allow us to return to popular venues without being seen to flog a comedically dead horse, I came up with a three-part sketch that featured a riff on the character. The central joke was that Holmes was frequently off his head due to injecting homegrown narcotics, a fact he endeavored to hide from Watson (when asked to explain the presence of his junkie paraphernalia in the sitting room he offers my favourite line, suggesting it must be ‘Junkie mice, writhing in torpid ecstasy in the wainscoting. Bedeviled rodent fiends, when will they learn to be satisfied with the glories of cheese?’) Such nonsense went down well. It also offered me something of a workout during the second half when, out of Watson’s eye-line, I as Holmes fought with a corpse, considerable Kensington Gore was shed and somersaults thrown.

At some point during all this silliness the bug bit and the pair of us began to give thought to playing the roles seriously. Might a Holmes project be what we needed to improve things? Get bums on seats, earn a few quid and play roles we had always been drawn to?

I enquired about the rights for Jeremy Paul’s The Secret of Sherlock Holmes, a play originally suggested by actor Jeremy Brett to celebrate the centenary of the character. I found that the agency that held them had long fancied the idea of reviving the show and, before we quite knew what we were doing, Phil and I were booked in for a test run at the Civic Hall in Stratford-upon-Avon, a particularly supportive (and large) venue. There were murmurs of a tour, hints at crossing the Atlantic, three-pipe dreams all.

It took remarkably little time for panic to set in. The pressure of playing Holmes terrified me and the ghost of Jeremy Brett loomed. The role had done Brett few favours, being the trigger for a series of breakdowns as his bipolar condition took its toll.

“Some actors,” said Brett, “fear if they play Sherlock Holmes for a very long run, the character will steal their soul, leave no corner for the original inhabitant.” It could be argued he proved that theory correct. “Holmes is the hardest part I’ve ever played,” he also admitted, “harder than Hamlet or Macbeth. Holmes has become the dark side of the moon for me. He is moody and solitary and underneath I am really sociable and gregarious. It has all got too dangerous.”

Yes, Holmes consumes. In my determination not to embarrass myself and successfully present a valid interpretation of the character, I became somewhat delusional in my attempts to play the role. I had decided I would compose the incidental music and commenced violin lessons so as to be able to play on stage. I began smoking filterless cigarettes as well as a pipe. At one rather shameful point I even set off to buy cocaine so as to be able to inject a seven-percent solution of it. Phil spared no time in making it clear what a stupid idea that was. Quite right too. Sorry Phil.

Of course this was all just window dressing. A character can never wholly be found in the barrel of a hypodermic syringe.

Internally I was becoming more morose and self-questioning. Holmes is not a cheerful character and trying to duplicate his personality was having an effect (though it is an interesting point made recently by screenwriter Steven Moffatt that we can get falsely bogged-down in the received wisdom of Holmes’ trappings, if you read the stories, he says, you’ll find far more references to Holmes laughing than you will of him taking drugs).

As the show approached I became more and more convinced that I was about to completely tank. Phil -- always the one who wore his nerves on his sleeve, unlike this faux cocky git -- was turning in an excellent performance as Watson, genuine and rich, full of emotion and gentility. I was hammering out a weak impersonation of Brett.

And then, months became days and then we were onstage. Tickets sold well which was a relief. Even when an actor’s confidence is at an all time low a lack of audience is to be feared, you’d think I’d be glad of empty rooms but the atmosphere of spectators always helps. The venue was being used during the day by the Carpe Diem Theatre School (the literal translation of which, I insisted, was “Fish of God”, the sort of latin joke that appeals to dead Romans with no sense of humour). We benefited from their students attending the show and the reviews were positively gentle.

On the last night I found myself on the outside of a little too much whisky, stripping off and hurling myself into the Avon. A handful of the afore-mentioned students went too (I particularly remember one girl, exposing a pair of briefs with a gold star on the front that brought to mind star’s dressing rooms). Floating in that soup of sewage and shopping trolleys I caught a glimpse of Phil, sat down on the bank with a look of thorough disapproval on his face. That’s my Watson, I thought, washing his hands of a self-destructive Holmes. As I floated there I decided that, all things considered, it’s sometimes best to draw a line between work and pleasure. Avoid your heroes. Some of them can contaminate and you’ll never be truly happy allowing their influence over you. No more Holmes, I thought (though other factors would rob that decision from me anyway), steer away from the obsessions. I wasn’t to know that a few years later... quite a few actually... I would find myself with a different career but the same opportunity. Would I write a new novel featuring Holmes?

Of course time has taught me a few things, not least of which -- and this is Phil’s fault -- that the stories are just as much about Watson as they are Holmes. Also, when it came to writing The Breath of God it wasn’t just Holmes’ head I was climbing into, it was Conan Doyle’s. Accordingly I have taken myself far less seriously than that young man floating in a river did. I have written a romp, a fast-paced adventure that, while it may have something to say about the conflict between rationalism and the supernatural seeks to thrill more than preach. Conan Doyle wished to excite his readers, to keep them turning the pages. That’s as noble an aim as a storyteller can aspire to and I let it be the singular aim of my book. There’s nothing wrong with aiming to entertain, something someone really should have explained to my younger self. If he’d known that he might have been a little easier on himself.

He’d probably still have jumped in the river though, swimming around until a passing homeless guy -- famed locally for his mean temper and lunacy -- strolled over and mentioned how even he wasn’t mad enough to swim in the Avon. That young man never was very sensible.

Published by Titan Books, Paperback £7.99

Published by Titan Books, Paperback £7.99

Released 7th October 2011