Crime author James McCreet wonders why women make up the majority of crime fiction readers

In April 1837, a court reporter at the examination of notorious murderer James Greenacre noted that the majority of people in the public gallery were “well dressed females.” As the trail continued and the authorities forbade access to ladies on account of the grisly details, these same females went to great lengths to observe the proceedings, seeking ‘special favour’ and paying a sovereign apiece to enter.

What was it about the case that so intrigued these Victorian ladies? Certainly, it was a brutal one of a serial philanderer and fantasist who had dismembered his lover and distributed her body parts around London to be found by a shocked populace. Greenacre himself was articulate and moody – a ‘bad boy’ in every sense – and by his side throughout the trial was another of his unfortunate molls: an accomplice who would eventually hang with him.

The interest in this largely forgotten case is essentially the same female interest in the murder narrative that persists to this day. Anecdotal evidence suggests that perhaps 70% of crime fiction buyers are women. It is largely women who make up the reading groups, the bloggers and the festival goers with a taste for the metallic tang of blood. At a recent reading of mine, only five of the fifty attendees were male.

As a crime writer (and as a male), I find the phenomenon fascinating and can’t help but look for motives or clues, especially when women themselves are so often the victims of both fictional and factual crime. The case of Greenacre provides a classic example, not only in the victim being female but in the collateral damage it subsequently exposed. It seems that, as disparate body parts were collected prior to arrest, a number of families came forward to report women missing in London. There is no record of whether they were ever found.

Could it be as simple as the sexual lure of the murderer – the well documented appeal of the serial killer? The ‘Night Stalker’ Ted Bundy received hundreds of love letters in prison, as has ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ Peter Sutcliffe. Such men radiate a danger that might represent sensual frisson to some, or the need for salvation to others. There is a power in the documented killer that can excite passion and pity in equal (and possibly conflicting) degrees. To save him or to survive him, to be selected by him or to select him is a variety of female triumph over the Heathcliff figure.

However, the pathology of the serial killer’s correspondent is ultimately just a single element of the female crime reader, for whom fiction rather than brute reality is the main attraction. The old trope of death and sex might ring true throughout the genre, but it is too simplistic in itself to explain the appeal. There must be more, and deeper, motives.

But let’s not leave sex just yet – it provides a handy allegory. If women are the predominant readers of crime fiction, perhaps we can say that men traditionally favour the crash-bang narratives of Andy McNab or James Patterson. Such stories are basically pornography, supplying the instant and explicit gratification of violence combined with the fetishism of weapons and strategy. In contrast, the typical crime narrative represents something more akin to eroticism: a slow seduction of the reader that rises through a teasing accumulation of clues to a shuddering climatic denouement that leaves the reader fully satisfied. Could this – the neuro-sexual differences of gender – really be a factor?

Cod-psychology may well be a red herring, but it is a compelling one. The questions implicit in the genre are of two broad schools: the ‘what’ and the ‘who’ can be simple enough, but the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ call for deeper analysis. As a man, I am prone to look for the quick, objective answer. I suspect that the female reader will not be satisfied with such superficialities unless the multiple subjective contexts can be more sensitively examined. As in marriage, the ostensibly quick testimony of the male slowly becomes a comprehensive case for the prosecution.

In the end, it comes down to the solution and how you get there. The way into the labyrinth of the crime narrative has many dead-ends, mis-directions and mirrors. Those with a sensibility delighting in the complex and contradictory may find a deeper pleasure in its twists and a greater satisfaction with the eventual egress. As for my role as both writer and reader, I can only say that the well dressed female was, after all, why the hero entered the maze in the first place.

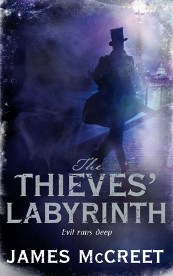

James McCreet’s latest book, The Thieves’ Labyrinth, is out now (Pan Macmillan).

BUY IT

medical abortion pill online

click here cytotec abortion pill buy online

buy abortion pill

read abortion pill online purchase

i dreamed my husband cheated on me

click here website

letter to husband who cheated

femchoice.org why men cheat on beautiful women

abortion in islam

go cheap abortions

cialis coupon free

open coupons for cialis 2016

how much does it cost for an abortion

open medical abortion pill

bystolic coupons for free

forest laboratories patient assistance

free prescription drug discount card

cialis coupon cialis savings and coupons

buscopan hund

go buscopan preis

allotment

click allo allo

amoxicillin antibiyotik fiyat

amoxicillin-rnp amoxicillin antibiyotik fiyat

prescriptions coupons

akum.org 2015 cialis coupon

revia reviews

open naltrexone alternatives

low dose naltrexone for pain

open naltrexone challenge

vivitrol treatment

ldn capsules naltrexone for multiple sclerosis user reviews