|

Clearing the Decks

Anticipating my retirement from this august column next month, I have been attempting to organise the Aladdin’s cave which laughingly passes as my filing system. As always happens, I find something which distracts me and prevents me from doing any serious work for several hours (some would say days), in this case two things.

Firstly, a file copy of one of the earliest, perhaps the first, Getting Away With Murder columns, dating from the summer of 1999.

In those days GAWM, as it quickly became known, appeared in the quarterly Sherlock Magazine and the initial commissioning was done at an Arthur Conan Doyle celebration event at Crowborough in Sussex, where Harry Keating and I had been pontificating on the state of crime fiction. After our talk, the editor of the magazine approached me and asked if I would write a regular column on anything but Sherlock Holmes, which was already covered in great detail.

It seemed to go down well enough, even prompting the magazine to give me a totally unauthorised personal ident.

Following a hiatus in the publication of Sherlock, Mike Stotter, the editor of Shots which had recently gone electronic from magazine to ezine asked if I would consider continuing the column ‘online’ as the young people say and the earliest surviving example in the archive dates from 2006. At some point, George Easter got in touch and asked if he could syndicate the column in the American magazine he edits, Deadly Pleasures, a trans-Atlantic alliance which has remained to this day.

Sifting through GAWM ephemera also turned up this photograph from a publisher’s party (remember them?) of perhaps ten years ago, featuring the ‘three wise men’ of British crime fiction.

Some years later, Barry Forshaw, Peter Guttridge and I did our best to destroy that reputation by appearing together as the grande finale to a CrimeFest convention in Bristol in a heated debate about something or other.

Who knows if we will ever see such a line up in public again?

Reissue of the Month

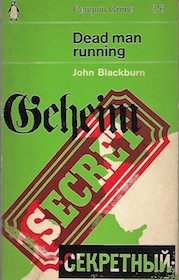

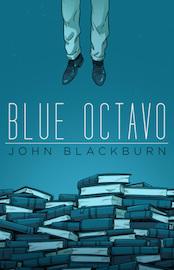

I have always enjoyed the thrillers of John Blackburn (1923-93), regarding them as something of a guilty pleasure, though quite why I should feel guilty I was never sure.

Blackburn had the knack of writing both convincing spy thrillers and gothic horror stories (Christopher Lee was said to be a big fan) often, uniquely, combining the two genres. I have had the pleasure of bringing back into print one of his novels (The Young Man From Lima) as a Top notch Thriller and being asked to write an Introduction to another (Blue Octavo) in 2013 when a new edition was published by American enthusiasts Valancourt Books.

Valancourt have again to be praised for now reissuing of one of Blackburn’s early Cold War thrillers Dead Man Running, although I already hold them in the highest esteem for republishing (and introducing me to) Blackburn’s 1967 historical novel The Flame and the Wind. Set in the Roman Empire of the first century, Sextus Ennius, a spy of the Department of Vigilance (Rome’s equivalent of MI5, or perhaps the KGB) is sent on a mission to the Middle East by a retired Governor of Judea named Pontius Pilate to report on the dangerously seditious sect forming around the execution, and possible resurrection, of a mystical local trouble-maker...

Talking Pictures

It wasn’t actually on the Talking Pictures channel, but one of the many Freeview channels in the 30-40 range where I caught, by chance, the 1965 spy film 36 Hours starring James Garner, Eve Marie Saint and Rod Taylor of which I was previously unaware.

It was something of a treat with a plot reminiscent of The Manchurian Candidate and perhaps a couple of vaguely-remembered episodes of the original Mission Impossible series. Basically, a US intelligence officer is brainwashed into giving the nasty Nazis the detailed plans for D-Day’s Operation Overlord, or is he? After numerous double bluffs, D-Day goes ahead without a Spoiler Alert and James Garner escapes from captivity and heads for the Swiss border. Unlike his earlier attempt in The Great Escape, this time he makes it.

Flashback of the Month

Mark Timlin once said that his friend Robin Cook was the only person ever to have voluntarily changed his name to Derek (Raymond), which is probably unfair, but I remember thinking, way back in 1966, that it was an unusual name for a globe-trotting American superspy determined to outdo James Bond on every level. I refer, of course, to Derek Flint, as played with tongue firmly in cheek, by James Coburn in two films, Our Man Flint and its sequel In Like Flint. My memory was jogged by the recent discovery that there was a book of that first film. Mark Timlin once said that his friend Robin Cook was the only person ever to have voluntarily changed his name to Derek (Raymond), which is probably unfair, but I remember thinking, way back in 1966, that it was an unusual name for a globe-trotting American superspy determined to outdo James Bond on every level. I refer, of course, to Derek Flint, as played with tongue firmly in cheek, by James Coburn in two films, Our Man Flint and its sequel In Like Flint. My memory was jogged by the recent discovery that there was a book of that first film.

Flint was a master of unarmed combat and a yoga technique which made him dead to all intents and purposes and, being the Sixties, he naturally had a harem of pliant dolly birds. He was an agent of Z.O.W.I.E. (Zonal Organisation World Intelligence and Espionage – if you have to ask) and in Our Man Flint he tackles the problem of climate change, and by that I mean the evil baddy who has found a ways to control the weather and is blackmailing the world.

In one of the films, I forget which, the evil genius was called Hans Gruber who, twenty years later, was still in the evil business as the ruthless villain in Die Hard, proving you just can’t keep a good master criminal down. Possibly the one thing most people of a certain age remember from the films is the ringtone of the red telephone on the desk of Flint’s boss (wonderfully played by the lugubrious Lee J. Cobb). It can still be heard on You Tube and I was wondering if I could download it to my burner Nokia.

Recommendations I Will Follow

Sadly, my review copy of Our American Friend by Anna Pitoniak [No Exit] reached me too late for serious consideration this month, but it has elbowed its way into my to-be-read pile on the basis of recommendations from two writers I particularly respect.

Firstly, Lee Child declares it to be ‘Spectacular – a global thriller with pace, tension and ever-higher stakes’. Then to seal the deal, my absolute favourite American writer of historical spy fiction, Alan Furst, describes it as ‘A smart political thriller, sharply observed and well-written’.

Scandi dystopia? Surely not.

My old friend Reginald Hill had, in our private correspondence, an alter ego named Professor Underhill, who in latter years spoke only in Old Norse having devoted his life to cataloguing all the jokes in Scandinavian crime fiction. It was not a lengthy list and indeed the very gloominess of much ‘Nordic noir’ is what appeals to many readers, yet however grim a view of life it presents, it could never be described as truly dystopian fiction. My old friend Reginald Hill had, in our private correspondence, an alter ego named Professor Underhill, who in latter years spoke only in Old Norse having devoted his life to cataloguing all the jokes in Scandinavian crime fiction. It was not a lengthy list and indeed the very gloominess of much ‘Nordic noir’ is what appeals to many readers, yet however grim a view of life it presents, it could never be described as truly dystopian fiction.

For that, fans of Brave New World and 1984, can now turn, for the first time in English, to Kallocain by the Swedish novelist and poet Karin Boye (1900-1941), which is now published as a paperback penguin Classic. Written in the early days of WWII against a backdrop of Nazi military victories across Europe and no doubt inspired by Karin Boye’s residency in Germany at the time Hitler took power, the novel depicts a totalitarian state where ‘police eyes’ and ‘police ears’ are everywhere and a mid-ranking scientist invents a drug – the Kallocain of the title – which makes everyone who takes it tell the truth; surely just the thing to create a new world untroubled by individual thought or, heaven forfend, dissent.

A Well-Deserved Triumph

I am delighted for my old chumette Lindsey Davis as her 1989 novel The Silver Pigs has been chosen as one of his favourite pieces of fiction about Ancient Rome by historian Tom Holland – my go-to guy when it comes to Roman history.

Writing in The Times (American readers please note there is no such thing as The London Times despite what Google says) this month, Holland lists his favourite fictional depictions of Roman life both high and low. Lindsey’s debut take on a private eye operating under the rule of Emperor Vespasian is picked alongside The Satyricon by Petronius, I, Claudius by Robert Graves and Rosemary Sutcliffe’s The Eagle of the Ninth, so she is in very good company.

Holland declares that (her series hero) Falco, is ‘a wonderfully drawn character, the plots are invariably thrilling, the humour is gentle and warm, the research is impeccable, and the portrait of the imperial capital in all its splendour and squalor is unforgettable.’ The series is well worth a Triumph; the Romans would have given her one.

The Name’s Familiar

When I saw that Joffe Books were offering a ‘box set’ of e-books of the adventures of (the Hon.) Duncan Morant as he served on Motor Torpedo Boats during WWII, I felt sure – though I had read none of the books – that the name of author, Alan Savage, was somehow familiar.

It was, I soon realised, one of the many pen-names used by the ultra-prolific Christopher Nicole, who wrote over 200 novels in various genres from 1957 onwards. He was best known, writing as Andrew York, for his 1960s series of spy thrillers featuring special agent Jonas Wilde, beginning with The Eliminator, which now have something of a cult following and The Expurgator, pictured here from 1972, is really quite rare.

A long-time resident of Guernsey, I was able in the years before his death, to find Christopher a DVD of the 1967 film Danger Route, which was based on that first Jonas Wilde novel, after he told me that he had long since worn out his only VHS copy.

|

|

BOOKS OF THE MONTH

The latest novel in Graham Hurley’s magnificent Spoils of War series, The Blood of Others [Head of Zeus] concentrates its attention and that of the reader on one incident in WWII, the ill-fated commando raid on the French port of Dieppe in 1942, which took a heavy toll on the mostly Canadian attacking force. As with all Hurley’s war stories, there is far more to this novel than sheer military action, though that is, as usual, superbly done, rather the genesis of the raid is covered from both the Canadian and German sides, with cameo roles for Willi Schultz of the Abwehr and Tam Moncrieff of MI5 from earlier novels. Real players in the game include Lord Mountbatten, Lord Beaverbrook and Noel Coward. Historical fiction of the highest order which teaches that however just the cause, war is folly.

A global internet-based fraud selling counterfeit drugs which involves criminal elements from Russia, Ukraine, India and Australia with a base in Austria worthy of a Bond villain, is surely in need of a good linguist as when the guns come out, Google Translate simply isn’t adequate. In The Conspirators by G.W. Shaw [Riverrun] a nerdy (multi) linguist is seduced by the promise of a huge pay-check (he wants to get on the property ladder in Brighton so it has to be huge) and agrees to become a translator, mostly translating threats from Hindi into Russian and vice versa. Pretty quickly our good-hearted hero Jacob finds himself a prisoner and realises that the business his employer is in is not only illegal but highly dangerous and there is absolutely no honour among thieves. Jacob’s naivete extends to believing that the CIA want him to communicate by messages written on paper aeroplanes and he is easily cowed by a brutal Russian crime lord, but his aptitude for languages, and one in particular, sees him through all the double-crossing and violence. This is fast-moving, superior thriller-writing at its best.

Peter Hanington has a journalist’s nose for stories likely to make tomorrow’s Radio 4 news, which is not surprising as he was until recently a BBC Radio reporter. His latest novel, The Burning Time [Baskerville], is a headline-grabbing thriller which encompasses Downing Street chicanery, climate change gurus seeding clouds with ‘diamond dust’, attack drones, assassinations and assorted conspiracies organised by the shady but all-powerful solid-fuel lobby, all on a global scale, the action moving from Spain to Australia via America and the academic groves of Oxford. Investigating all this is a radio journalist of the old school, William Carver, who whilst officially employed mentoring the next generation of journalists, is not yet prepared to hang up his Uher recorder, or keep his nose out of a good story.

Until this year, I had not read a book set in wartime Singapore for ages. Then I discover the work of Ovidia Yu and, this month, Tokyo Time [Brash Books] by Australian Dawn Farnham. During the Japanese occupation of what was known as Syonan, the population had to adopt a Japanese calendar and operate on Tokyo Time, and although the British have surrendered and the fighting may be over, detectives still have to detect crimes and murderers still murder. Eurasian homicide detective Martin Bach has to investigate the killing of the trophy wife of a rich, well-connected, businessman with virtually no resources and the need to guide his new boss, an aristocratic Japanese, the former police chief of Nagasaki with penchant for Sherlock Holmes stories, through the local underworld. Both having to keep one eye over their shoulders for the dreaded secret police. Tokyo Time offers a thoroughly satisfying murder mystery and, in addition, a fascinating portrait of a muti-racial, multi-cultural society which finds it has exchanged one set of imperial overlords for another.

Yulia Yakovleva’s Death of the Red Rider [Pushkin Vertigo] is cleverly billed as the second in a ‘Leningrad Confidential’ series, so presumably there will be a quartet, at least. The Leningrad in question is that of 1931, on the eve of Stalin’s great purge and other horrors, and Comrade Inspector Zaitsev is landed with a bizarre murder in the world of trotting (aka harness racing) when a favourite horse collapses and throws its rider/driver. Bizarrely, it seems that the horse was the intended murder victim which leads Zaitsev to a cavalry school in the Ukraine where secrets stay buried and mutiny is fermenting. The setting of 1930’s Russia is brilliantly realised and the author comes up with a devilishly cunning method of murdering a thoroughbred racehorse.

Prey For The Shadow [MacLehose] by Javier Cercas is the second outing for his police detective Melchior Marin, whose beat is the ‘perpetual slumber’ region of Terra Alta in Catalonia near Barcelona. When I read his first outing, Even the Darkest Night (which has recently won a CWA Dagger for crime novels in translation), I thought that here was a fictional detective worth keeping tabs on and I am delighted to say that I was, as usual, right. All fictional detectives have troubled backgrounds, but Melchior Marin’s would take some beating as the son of a murdered Barcelona prostitute, who then does time in prison, sees the light, becomes a policeman and, almost accidentally, a hero after a shoot-out with terrorists. His second investigation starts with the populist female mayor of Barcelona facing blackmail over a sex-tape from her student days and Melchior’s dark heart goes out to her. This is a multi-layered, deeply satisfying crime novel which cheekily breaks the fourth wall when Melchior spots someone reading Even the Darkest Night, which he dismisses as ‘all lies’.

After a wave of excellent American rural noir thrillers, we are back in hard-boiled urban noir territory with Every Hidden Thing by Ted Flanagan [No Exit] where a night-shift paramedic trying his best to save lives finds his own at risk. Not only from a ruthless city mayor covering up an unwanted pregnancy, who has brutal ex-cop as an enforcer, but also from a well-armed loony survivalist ‘militiaman’ on twisted mission of revenge. A gritty, unrelenting tale of despair and violence in a diamond-hard cityscape.

At first glance, I was sure I knew who the ‘old rogue’ in question was, but then I realised the title read Limehouse and not Whitechapel. The Old Rogue of Limehouse by Ann Granger [Headline] is set in 1871 – too early for the Ripper’s gruesome activities – and it is soon clear that the old rogue in question is reclusive antiquarian and suspected fence for stolen jewellery Jacob Jacobus, who suffers from agoraphobia – a condition first diagnosed that same year. As Jacobus never left the upper floor of his house, somebody has to get in – be let in – to murder him, which of course happens just as Scotland Yard detective Inspector Ben Ross learns of a jewellery theft from the upper-crust Roxby family in Hampstead. Coincidence? Unlikely. The action moves smoothly across Victorian London and its class barriers, in twin narrative streams by the affable Inspector Ross and his bright wife Elizabeth, all flowing from the stylish pen of Ann Granger, one of our most fluent writers of traditional crime novels.

If you go down to the woods today.... well, just don’t. Not if, that is, if they are anything like the spooky Gloucestershire forestry described in The Clearing by Simon Toyne [HarperCollins], where nasty things happen, particularly to young women. Ancient terrors from local folklore (the ‘Cinderman’ of Cinderford), indifferent policemen and long-buried family secrets combine to paint an unnerving picture of the Forest of Dean, despite its designation as an area of outstanding natural beauty. There are, perhaps, too many of the expected serial-killer-thriller tropes, such as the night vision goggles, an escaping female who falls and twists an ankle and the constant frantic search for more than one bar of signal reception on a mobile phone, but none the less, a pacy, occasionally jolting, read.

In All Of Us Are Broken by Fiona Cummings [Macmillan], many a character enjoys a somewhat esoteric name: Galen, Melissa, Dashiell (!), Aliyah and police detective Saul Anguish, yet the story starts in the rather boringly-named Essex town of Midtown-on-Sea. But Essex is only the jumping off point for a bloody road trip north for two blithe psychopaths and the family with whom they collide. Reminiscent of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek on their killing spree in Badlands, though the lovebird killers here are nastier, presenting a mother with a real Sophie’s Choice about her children, this is not for the faint-hearted.

Rumours of My Demise

Although it is probably my fault, announcement of my retirement has somehow transitioned into rumours of my demise if not total extinction. I would reiterate, for the benefit of the nay-sayers and wishful-thinkers, that I am only retiring from this monthly column, although a Christmas Special for Shots has been green-lit by the editor. Although it is probably my fault, announcement of my retirement has somehow transitioned into rumours of my demise if not total extinction. I would reiterate, for the benefit of the nay-sayers and wishful-thinkers, that I am only retiring from this monthly column, although a Christmas Special for Shots has been green-lit by the editor.

I will still write for the obituaries department of The Guardian and for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and carry on reminiscing about crime novels and thrillers of days gone by in my Bargain Hunt column in the magazine Crime And Detective Stories (CADS).

And I will also continue my ‘continuation’ novels featuring Margery Allingham’s Golden Age detective Albert Campion, which reminds me that Mr Campion’s Memory will be published by Severn House in September.

I am delighted to report that three of my regular readers have already pre-ordered the title, though I have no idea why the other two are dragging their feet.

One more to go!

The Ripster.

|