| Spying in Whitehall

(and Pimlico)

Last month I had the honour to give the annual Richard Lancelyn Green lecture to the Sherlock Holmes Society of London in the impressive halls of the national Liberal Club in Whitehall.

Not being an expert on matters Sherlockian, but facing a hall full of them, I chose to give my sermon on early British spy fiction, a genre which emerged just as the great detective’s career was being revealed to the public. (A text of the lecture can be found in the Features section of Shots.)

I found it a very pleasant evening mingling with a wonderful variety of people brought together by their admiration for a fictional character under the rather stern gaze of the statues and portraits of William Gladstone. I would like to think it was the spirit of Liberalism which was responsible for the miracle which occurred during the question-and-answer session after my talk, when a cooling glass of water was instantly changed into an even more refreshing pint of Timothy Taylor’s Landlord bitter.

Perhaps such mysteries are best left unexplained. [Thanks to Jean Upton and Paul Gillings for the pictures.]

And this month, a further adventure into the world of fictional espionage when I was invited to a London meeting of the international Spybrary Podcast group. The intention had been to go on a walking tour of famous London spy locations, but torrential rain put paid to that idea.

Undeterred, a gaggle of enthusiastic Spybrarians, including David Craggs and Shane Whaley, took cover in the famous Morpeth Arms (directly across the Thames from MI6 headquarters) preferring to get soaked inside rather than drenched outside.

Re-Read of the Month

I have long sung the praises, to anyone who would listen and many who would not, of thriller-writer Francis Clifford, though I have only ever met two readers who also admitted to being big fans; one being the late Harry Keating, the other Professor Barry Forshaw. In advance of tackling a pair of Cliffords I realised I had never read, I picked up one of his spy stories on a whim, just to re-acquaint myself with the author. I was immediately hooked because I had forgotten just how good Drummer in the Dark was. I have long sung the praises, to anyone who would listen and many who would not, of thriller-writer Francis Clifford, though I have only ever met two readers who also admitted to being big fans; one being the late Harry Keating, the other Professor Barry Forshaw. In advance of tackling a pair of Cliffords I realised I had never read, I picked up one of his spy stories on a whim, just to re-acquaint myself with the author. I was immediately hooked because I had forgotten just how good Drummer in the Dark was.

Published in 1976, it tells of the British intelligence operation to uncover and disrupt the supply of a new radio-controlled bomb (called a ‘Touchbutton’ here but today we would label them as sophisticated IEDs) being used by an extremist group of Irish nationalists. The action flits between London, Northern Ireland and Poland, from where the Touchbuttons are being smuggled. The narrative follows not the bombers or their political manipulators, but the spies (and the smugglers) in the shadows in an attempt to stop an increasingly violent campaign of terror, and concentrates on the cost to the individuals involved, especially their private lives.

Drummer in the Dark was the last novel written by ‘Francis Clifford’ (Arthur Bell Thompson, 1917-1975) and was published in 1976. His thrillers were much lauded in Britain and the United States and his writing often compared to that of Graham Greene, Elleston Trevor and Gavin Lyall, though his particular grasp of the psychology of men and women under pressure - particularly men in battle – was unrivalled. An outstanding thriller writer, whose work remains inexplicably and disgracefully forgotten.

All My Yesterdays

Taking my cue from the old television show All Our Yesterdays, which looked back twenty-five years ago (and which ended in 1989), I occasionally dig out my Crime Guide column to see what I was reviewing for the Daily Telegraph a quarter of a century ago. In those heady days back in November 1997 – when you could get 2.3 Euros to the £, a litre of petrol cost 60p and a pint of bitter was £1.65 – my column was dominated by debut novels.

Grabbing my attention were Greg Williams (who went on to write thrillers as Gregory Lee) with Diamond Geezers; the wonderful – and wonderfully named - Canadian Sparkle Hayter with What’s A Girl Gotta Do?; Jon Stock who progressed to some fine spy stories but is today better known as J. S. Monroe, debuted with The Riot Act; Paul Johnston launched his furiously funny satirical series about an independent Scotland dominated by the puritanical city state of Edinburgh, in The Body Politic; and Jason Starr made instant, and very uncomfortable, impact with Cold Caller. Jason continues to be a leading (dark) light in American noir writing and has been known to write in partnership with that godfather of Irish noir, Ken Bruen.

Stocking Fillers

I have no idea how many sleeps it is to Christmas, but Bonfire Night usually signals the time, here at Ripster Hall, when lists are made of presents which would be appreciated and for presents, read books. My personal list of titles, none of which have anything to do with crime fiction, is already complete – and available on request – but for the undecided, here are a few possible suggestions for Christmas stocking-fillers.

HarperCollins have produced splendid new hardback editions of two Agatha Christies from the 1920s, The Mysterious Affair at Styles and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which I think should be regarded as classics of crime fiction. Styles because it was her first published novel and introduced Hercule Poirot to the world; Ackroyd was, and is, well, a classic.

Ackroyd comes with an Introduction by Louise Penny (see Books of the Month) who describes it as Dame Agatha’s ‘masterpiece’ and fully acknowledges the influence of Christie on her own crime-writing career.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles has an Introduction by Dr John Curran who explains how the original denouement, where Poirot reveals the solution to the mystery from the witness box in a courtroom scene, was changed to an exposition given to all the suspects gathered in the drawing room, a technique he was to adopt in many further adventures (and be much parodied for). The new edition actually includes the original scene as an appendix, so it is a unique Christie in that it has two Chapter 12s.

To get into the true spirit of Christmas, the famous Collins Crime Club celebrate another Queen of Crime, Ngaio Marsh, with a 50th anniversary paperback edition of Tied Up In Tinsel. It’s Christmas party time at the country house Halbards, where one of the guests is the ‘celebrated painter’ Troy Alleyn. When foul play takes place, you can be sure her husband, Superintendent Roderick Alleyn, will be along shortly.

The ultimate Christmas mystery this year must be Alexandra Benedict’s Murder on the Christmas Express [Simon & Schuster], which is set aboard the sleeper train to Scotland on Christmas Eve, with heavy snow forecast, a former police detective anxious to get home to her pregnant daughter and there appears to be a serial killer on board. Who would have thought it? To add value to the mystery plot, the book also contains Christmas quizzes (answers provided), answers to puzzles within the story, a recipe for a substantial sweet treat, and there are extra kudos points for anyone who can spot references to twelve Kate Bush hits in the text. (Twelve? Who knew?). Great fun.

Christmas is traditionally a time for anthologies, either on a particular Christmassy theme or a collection by a particular author. As I have not yet seen Maxim Jakubowski’s Death Has A Thousand Faces [Head Shot Press], I cannot say if any of the stories included are seasonally appropriate and I suspect, knowing Maxim’s work, they lean to the very dark side and the erotic. Should any of the stories feature an established Jakubowski character called Cornelia, watch out for an unusual tattoo in a very unusual place.

|

|

Czech-ing In

There was a time when my knowledge of modern Czechoslovakia (as was) was limited to the famous products of Pilsen, Budvar and Brno, the infamous ‘Munich Agreement’ of 1938 and the wartime Operation Anthropoid, which has been much filmed and written about. Since then I have mostly learned about the post-war country thanks to thrillers, including by John Le Carré and Philip Kerr.

Recently I have been reconsidering four of my ‘Czecho’ collection, which cover the decades of Communist rule.

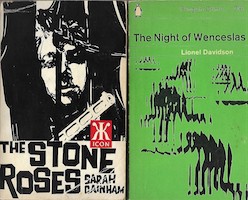

The Stone Roses (which did not provide the name for a modern beat combo from Manchester) by Sarah Gainham (pen-name of Rachel Stainer, 1915-1999) was published in 1959, but set some ten years earlier just as the Communists, backed by Russia, seized control. It is one of the least-known titles in the canon of British spy fiction, though not the most under-valued if the prices of second-hand copies are to be believed. A British ‘journalist’ is sent to Prague despite not speaking Czech to help exfiltrate a dissident before the Russian MVD can grab him. Unsurprisingly the dissident has a beautiful sister who in turn aids and hinders the escape plan which is further complicated by a female rogue agent with homicidal tendencies.

The Night of Wenceslas by Lionel Davidson (1922-2009) is an old favourite. First published in 1960, Davidson’s Ambler-esque tale of a reluctant spy on a mission to Prague won the author the first of his three Gold Daggers. Davidson, then a journalist, missed publication day and his immediate rave reviews as he was in Switzerland interviewing another best-selling author, Alistair MacLean.

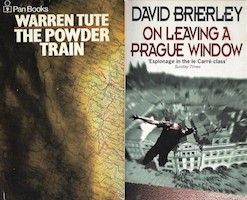

The Powder Train by Warren Tute (1914-1989), which I had not read before this month’s reassessment of Czechoslovakian titles, was first published in 1970 and is set in 1968, just after Russian troops had moved into Prague to crush the first blooms of liberalisation. Indeed the whole ‘powder train’ plot is based on the wave of student unrest generated in that year. The central character is George Mado, a disgraced British agent now dedicated to alcoholism and seducing (much) younger girls, and his complex, wayward mission covers all the period’s spy fiction hot spots: Oxford, Beirut, Moscow and Prague, though oddly not Berlin.

David Brierley’s On Leaving A Prague Window, published in 1995, is set after the end of the Cold War, as the heady days of the Velvet Revolution and the Prague Spring are in danger of turning sour. In its title – one of my all-time favourites – Brierley, with his customary sly humour, refers back to the famous Defenestration of Prague in 1618, which I remember, from my schooldays, was one of the flashpoints to spark off the Thirty Years War. I think I even remember the names of the two Papal emissaries who took that celebrated fall – Slavata and Martinitz – and I’m rather proud of that.

Hard Falls

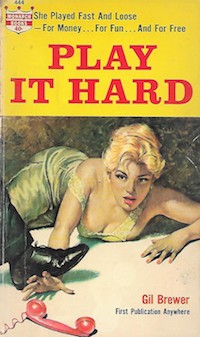

I have long meant, having seen his name referenced many times in the past, to read something by American pulp noir author Gil Brewer, not least at the urging of those hardboiled devotees at Stark House Press. Now I have.

Gilbert Brewer (1922-1983) churned out paperback originals with garish covers always suggesting sleaze rather than crime and detection in the 1950s and ’60s whilst struggling with alcohol and never gaining the recognition awarded to contemporaries such as Jim Thompson, David Goodis and Cornell Woolrich. In recent years, however, there has been something of a reappraisal of Brewer’s writing, always described as ‘brutalist’ with protagonists who were always losers as well as boozers, and in 2013 the Los Angeles Review of Books suggested he was better writer than Woolrich. Gilbert Brewer (1922-1983) churned out paperback originals with garish covers always suggesting sleaze rather than crime and detection in the 1950s and ’60s whilst struggling with alcohol and never gaining the recognition awarded to contemporaries such as Jim Thompson, David Goodis and Cornell Woolrich. In recent years, however, there has been something of a reappraisal of Brewer’s writing, always described as ‘brutalist’ with protagonists who were always losers as well as boozers, and in 2013 the Los Angeles Review of Books suggested he was better writer than Woolrich.

Play It Hard, published in 1964, is actually a very Woolrichian tale where the hero goes off on a week-end bender and returns to the Florida home he shares with his aunt having met a woman and married her on the spur of the moment. The trouble is the woman now claiming to be his wife is not the woman he married days before and how does he explain any of that to the girlfriend he left behind? His little holiday from work – he’s an over-worked mattress salesman (fill in a Carry On joke here) – was certainly some bender.

And that is part of the problem with our ‘hero’ Steve Nolan, who is not too bright to start with, handicapped by being almost permanently drunk and despite treating them appallingly, is fatally attractive to women. When no-one believes that his new wife is really a fake wife, Nolan blunders in to his own investigation after failing to get fake wife to admit she is fake by roughing her up in the bedroom and the shower, and occasionally tearing off her ‘skin-tight’ clothes. In fact, everything the woman wears is ‘skin-tight’- suits, jumpers, swimming costumes and nylon stockings (which would not be very attractive if they weren’t skin tight, would they?).

Despite all that, and the ultimate weakness of the motives behind the plot against the unsympathetic protagonist, the book hurtles along at a frantic pace with more than a few twists of suspense and sudden violence, and I am glad I read it.

There is, however, no peace for the wicked and those hardboiled aficionados at Stark House Press are now insisting that I try another author from the American era of classic noir and have sent me an advance copy of their forthcoming Stark House Film Noir Classic The Pitfall by Jay Dratler. There is, however, no peace for the wicked and those hardboiled aficionados at Stark House Press are now insisting that I try another author from the American era of classic noir and have sent me an advance copy of their forthcoming Stark House Film Noir Classic The Pitfall by Jay Dratler.

I was unaware of Joseph Jay Dratler (1911-1968), a screenwriter and novelist, and the fact that Pitfall had been turned into film noir in 1948, starring Dick Powell, Raymond Burr and the lovely Lizabeth Scott, all three having good track records in the genre. And I really should have been aware of Dratler as he was responsible for the screenplay of that truly classic film noir, Laura, which featured my soul mate Waldo Lydecker.

Books of the Month

Louise Penny has won multiple Agatha Awards at the annual fan convention Malice Domestic which (according to its website) celebrates traditional mysteries “which contain no explicit sex or excessive gore or violence” often leading to the somewhat pejorative description cosy. In A World of Curiosities [Hodder] Penny shows just what can be done with a ‘cosy’ cast of recurring characters, a ‘cosy’ (almost idyllic) setting of the Canadian village of Three Pines and a delightfully human and civilised detective who doesn’t carry a gun.

There are multiple puzzles for Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, and references to past cases. There may not be any ‘excessive gore or violence’ in it but the recalling of a Montreal school-shooting is utterly chilling. A class act from a classy writer.

A little over thirty years ago, a senior British crime fiction editor confided in me that it was difficult to establish good American crime writers in the UK, though she had great hopes for a new kid on the block called Michael Connelly and a book called The Black Echo. As things turned out, she was on to a good bet and three decades on, Connelly is still producing excellent police procedurals featuring his series hero Harry Bosch. His latest, Desert Star [Orion] sees his now ageing detective (Bosch is 70 but still dedicated to solving cold cases) again working with Los Angeles detective Renee Ballard.

Two cold cases – one of particular concern to a local politician and one very personal unsolved murder for Bosch – don’t take long to warm up and despite his advancing years, Bosch keeps up to speed with modern technology and methods of police work.

Harry Bosch is always, or almost always, the consummate professional police detective, determined to give justice to victims in danger of being forgotten.

For the first half of The Prisoner by B.A. Paris [Hodder] the reader is kept completely in the dark, but that’s okay because so too is the lead character. She is a young orphan girl who goes from sleeping on the streets of London to private jet to Las Vegas for a marriage of convenience to an obviously dodgy media millionaire. Along the way she witnesses two murders (just about everyone she comes into contact with gets knocked off) and ends up kidnapped and held in a totally blacked-out cell. Once released, she finds herself in a sort of counter-plot which is all explained in twenty pages of exposition (in New Zealand) and a kindly solicitor in Reading appears out of the blue in Dickensian fashion, to fulfil our heroine’s great expectations.

Despite the numerous suspensions of disbelief required, there are genuine moments of tension in The Prisoner even if most of the homicide is done off-stage, plus a poignant take on Stockholm Syndrome and it is written with such pace that it becomes addictive.

Whisper it softly but Jack Reacher just may have a rival in the form of ex-Special Forces soldier turned knight-in-shining-armour vigilante Mallory, who even, like Reacher, is not averse to hitching a ride or catching the bus to take him on his latest quest.

Red Mist by Ant Middleton [Sphere] is the second outing for Mallory, a character likely to dismiss a knife attack or a gunfight as ‘a little roughness,’ who finds not a damsel in distress, but a worried white-haired grandfather in a bar in rural Normandy. Fortunately, he has a grand-daughter who could be in distress in Paris and Mallory, itching to help the family, discovers that the grand-daughter has a boyfriend who, if not in distress, is certainly in trouble. The action moves swiftly to Marseilles and then Switzerland and the body count mounts as Mallory finds he has to resort to his military training and skills in order to survive. Yet even when not faced with imminent danger, the character seethes with an unspent energy and rage. Certainly not a guy to get on the wrong side of, and you feel that it might not take much to do so.

Late News

I have already apologised for missing the retirement party for Richard Reynolds of the legendary Heffer’s bookshop in Cambridge whilst I was on foreign assignment in September and now I must apologise again for posting a photographic record of the event, which arrived too late for the October column.

Anyway, better late than never, here is Richard Heffer not, I am assured, showing Richard Reynolds off the premises, standing in front of the plaque commemorating another Heffer, the founder of the business.

Toodles!

The Ripster

|