|

Basil Not-Fawlty

Back in 2002, Stephen Hunter’s Pale Horse Coming went immediately - with a bullet - into my Top Twenty all-time favourite thrillers, a book which certainly deserves to be still in print today. Now, two decades on, he delights rather than thrills with something completely different: a thoroughly diverting WWII spy story, Basil’s War [Head of Zeus].

Our hero - and what a hero! - is Basil St. Florian, an outstanding British agent selected for an impossible mission in between bouts of love-making with his mistress, Vivien Leigh. Basil is recruited by the Special Operations Executive - an organization ‘that would have welcomed Jack the Ripper to its ranks, possibly even promoted, certainly decorated, him’ - in order to find the key to a code which ‘Professor’ Alan Turing of Bletchley Park cannot crack. This requires Basil to be dropped into occupied France, make his way to Paris and infiltrate the library of the Institute de France to find and photograph an 18th century manuscript with the Gestapo and the Abwehr hot on his trail.

The indestructible Basil completes his mission with aplomb (no spoiler this), uncovering a Nazi agent within SOE and a Russian mole in Bletchley Park, and hopefully does it before Laurence Olivier gets back from scouting locations for his Henry V in Ireland.

There are a couple of Americanisms which do not sit happily on the stiff upper-lips of the British officers portrayed and I do believe at one point he confuses Oxford and Cambridge, but all that is forgivable in this splendid, gloriously entertaining romp. Basil St Florian may not be a prototype James Bond, but he certainly could be the secret agent Ian Fleming fantasised about being.

In some ways, Basil’s War reminds me of the Edgar Award-winning Augustus Mandrell trilogy of Frank McAuliffe of fifty years ago, and while the spy tradecraft is more credible and the plotlines less surreal, the author’s tongue is firmly in his cheek and the result is a refreshing change from the current crop of hard-as-nails ex-military heroes who take themselves far too seriously. In some ways, Basil’s War reminds me of the Edgar Award-winning Augustus Mandrell trilogy of Frank McAuliffe of fifty years ago, and while the spy tradecraft is more credible and the plotlines less surreal, the author’s tongue is firmly in his cheek and the result is a refreshing change from the current crop of hard-as-nails ex-military heroes who take themselves far too seriously.

Jail Time

To the despair of her many fans, I must reveal that crime-writer Elly Griffiths is going to prison in April.

The prison in question is in Horsens in Denmark, and Elly’s crime is to be a guest speaker at this year’s crime writing festival, known as Krimessen Horsens, which is held in the former Horsens prison where delegates (and guest speakers) are offered luxurious accommodation in refurbished cells. I am not sure of the timings of this year’s Krimessen convention (other than that Lock Down will be around 8.30 p.m.) but I am sure full details are available on the jolly old interweb.

Funnily enough, I discovered the Krimessen whilst searching the interweb (as you do) for ‘things to do in Copenhagen’ which is rather odd, as Horsens is two islands away from the Danish capital, on Jutland. It might be rather remote, but the archaeology there is supposed to be interesting, something I am sure Elly is aware of. Her series heroine, Dr Ruth Galloway, an archaeologist with a talent for solving modern crimes as well as prehistoric puzzles, certainly would be.

There is a new Ruth Galloway novel out this month (just in time for Elly’s incarceration in Jutland), The Locked Room [Quercus] which makes it, by my shaky arithmetic, the prolific Elly’s twenty-sixth novel in the last dozen years - and another (non-Galloway) novel arrives in October.

For legal reasons I was unable to attend the lavish lunch which marked publication but it is easy to see why the Ruth Galloway stories - she is a professional and independent woman with an unusual social network (which includes a Druid) - are so popular, given the added bonus of archaeology in that one could trip over a body at any time. In The Locked Room, the first body is found in the seemingly appropriately-named Tombland in Norwich. Now in my mis-spent youth, when Norwich was my stomping ground, bodies littering the streets around Tombland at closing time were not uncommon and rarely required the attention of an archaeologist, but this is comfortable British crime-writing and that first body is only the introduction to a mystery which unfurls just as Covid-19 strikes and the first lockdown clicks into place.

Farewell, My Marlowe

There have been previous attempts to revive or continue the career of Raymond Chandler’s legendary private detective Philip Marlowe, notably by the late Robert B. Parker (whose own work has spawned four continuing series) and ‘Benjamin Black’ (John Banville). Now Joe Ide, the creator of the ‘IQ’ mysteries has had a go with The Goodbye Coast [Weidenfeld & Nicolson], or so it is claimed.

I know I am old and my batteries are running down, but I honestly don’t see how this is a ‘Philip Marlowe’ novel other than the fact that the central character is called Philip Marlowe. I may have missed all the subtle references but I just don’t get the connection - any connection - to Chandler’s knight in shop-worn armour. The Goodbye Coast is an acceptable Californian PI story with a title which could have been coined by Ross Macdonald, but it reminded me more of The Rockford Files than anything penned by Chandler in his crusty pomp.

Footprints of a Gigantic Hound

A new imprint of ‘literary’ (whatever that means) crime and thriller fiction was launched last month, Baskerville, a division of publisher John Murray who, as the original publisher of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes books, have every right to use the iconic name that must never be mentioned when Crufts is on.

Based in Bristol, the home of CrimeFest, Baskerville’s first tranche of titles come from the far-flung corners of the crime-writing world, from Sweden, Japan and even Scotland. The imprint will also carry Mick Herron’s Slough House series, but the lead title for February is what has been described as ‘a Japanese classic’: Lady Joker by Kaoru Takamura, which was first published in 1997 but has not, I believe, appeared in an English translation before now.

Equally exotic, no doubt, will be Baskerville’s publication in July of Meantime, a debut crime novel by Scottish comedian Frankie Boyle and although I have no idea what it’s about, I feel there may be a clue in that title.

Berlin Game

Mention of my recent visit to Berlin sparked a flood of correspondence from readers wanting to share their experiences of the city.

Long-time reader (and authority on the life and work of Desmond Bagley) Philip Eastwood even sent me photographs of the divided city which he took in 1980, including this one looking over the Wall into East Berlin.

.jpg)

Coincidentally, and rather spookily, this scene is almost that of a key setting in Paul Vidich’s new Cold War spy thriller The Matchmaker (see Books of the Month).

Do Mention the War

Several decades ago, back in the last century when I had a proper job, I used to commute to London in the company of a Fleet Street journalist (and also a respected reviewer of crime fiction) who confided that his ambition, on retirement, was to write a British police procedural story set during World War II. He never did, but twenty years ago, in 2002, Anthony Horowitz created the wonderful television series Foyle’s War and veteran thriller writer John Gardner published Bottled Spider featuring Woman Detective Sergeant Suzie Mountford.

The police detective in wartime England has been featured with distinction by such as Laura Wilson and Rennie Airth among others, and now comes Jessica Ellicott with Death In A Blackout [Severn House], which is set in Hull in 1940.

This looks like the start of a series to feature WPC Wilhelmina (‘Billie’) Harkness, the unworldly daughter of a Wiltshire Rector who moves to Kingston upon Hull after the death of her mother and within the first twenty-four hours experiences the first Hull Blitz, finds a dead (murdered) body and joins the police force. With absolutely no knowledge of the geography of Hull (the fact that it was then proudly situated in the East Riding of Yorkshire is not mentioned) and with the aid of another constable (were there no detectives in Hull?), Billie survives the bombs and solves the crime in a Hull where nobody mentions Rugby League, they drink fresh coffee from cafetieres at breakfast and steal copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover from the public library.

[Apropos absolutely nothing, my ferocious Scottish grandmother was called Wilhelmina and no-one ever called her ‘Billie’.]

The author is American, and clearly so, not just from the spelling (‘center’, ‘offense’ etc.) but to the way street directions are given to pedestrians (‘take King Edward Street to Victoria Square...then turn east on Alfred Gelder Street...), but I suppose can be forgiven for not repeating the legend that the chimneys of the Hull Brewery Company were used as navigation aids by incoming German bombers - and the reason why the brewery survived the war unscathed. (A rumour probably spread by natives, like me, of the West Riding.)

John Gardner’s excellent Suzie Mountford series continued with The Streets of Town and three more novels before John’s death in 2007. It was quite an achievement for a man in his mid-to-late Seventies (he was also writing other things), who had been widowed in 1997 from his wife of forty years and was suffering increasingly complicated medical problems.

For the Suzie Mountford books, Gardner drew on his memories of the early war years and based the character on a former girlfriend, Patricia Mountford. When the first book was published, Patricia heard about it, got in touch and the pair were reunited. At the time of John’s death they were engaged to be married.

Cosy Cuisine

A television personality with a debut murder mystery where the detective is an amateur sleuth, a retired lady of a certain age. I know what you’re thinking, but I am referring to Rosemary Shrager, the celebrity television chef, teacher of cookery and the author of numerous cook books including the ambitiously titled Rosemary Shrager’s Absolutely Foolproof Class Home Cooking.

The Last Supper [Constable] features the murder of television chef at a Cotswold manor house solved by her replacement (and rival), celebrity chef Prudence Bulstrode, who has ‘dealt with all kinds of carcasses in her time’. Probably not a cosy read for vegans, but if you fancy pheasant for dinner, lots of handy tips are provided.

|

|

BOOKS OF THE MONTH

The Matchmaker by Paul Vidich [No Exit Press] is a stone cold, stone brilliant, Cold War spy thriller of the old school set in Berlin in 1989 as the Wall between East and West comes down.

The CIA are hunting a Stasi spymaster known as The Matchmaker due his establishment of a network of ‘Romeo’ agents who seduce and marry vulnerable women in the West, thus providing them with a cover for their activities. What neither the Stasi nor the CIA have reckoned with, however, is the reaction of one of ‘Juliets’ duped into a sham marriage, who has her own score to settle with The Matchmaker and both underestimate the capabilities of the amateur spy when suitably motivated, especially when it’s woman scorned.

Scenes of Berlin street-life at the end of the punk era, the actual crumbling of the wall and the subsequent ransacking of personal files in the hastily-abandoned Stasi headquarters, are vividly painted in Vidich’s spare prose. He even gives us a grieving woman at a graveside and a musician who played the zither in a nod to The Third Man, making The Matchmaker a book crying out to be filmed in black-and-white.

It is nearly thirty years since I reviewed Charlie Higson’s early crime novels and he has subsequently been concentrated on his television career and establishing the legend of the young James Bond. Now he returns to adult crime fiction with the darkly comic Whatever Gets you Through The Night [LittleBrown]. It is nearly thirty years since I reviewed Charlie Higson’s early crime novels and he has subsequently been concentrated on his television career and establishing the legend of the young James Bond. Now he returns to adult crime fiction with the darkly comic Whatever Gets you Through The Night [LittleBrown].

Set on Corfu, though the island’s tourist board won’t thank him, a tech billionaire has a palace/fortress where he confines, or rather grooms, a platoon of teenage female tennis players and our hero (and his team) is hired to extract one girl in particular, though it turns out she has her own plans for an escape. In the mix are any number of young idle rich professional party-goers, dodgy security guards, a drug-raddled mystic, the local brothel owner and, wouldn’t you just know it, Albanian gangsters.

Above all, there’s the bat-shit crazy tech entrepreneur presiding over a court which includes the fascinating - but totally bonkers - good time girl Pixie. Money, drugs and drink flow in copious quantities and the final ‘extraction’ is a fabulous set-piece. Along the way there are lots of movie references and is a salutary experience to readers of a certain age to discover that the plot of The Great Escape has to be explained to a younger generation.

Packed with good gags and eclectic information, such as the proper name for a Jet-Ski and what a Shibari Halo is (I have often seen one in action but never knew what they were called), the book is worth it for the return of a character Dennis ‘The Menace’ Pike from, if memory serves, Full Whack in 1995. Welcome back, Mr Higson...we’ve been expecting you...(Ed: Read Charlie Higson's exclusive feature here).

Stuart Neville’s new novel The House of Ashes [Zaffre] is the story of two sets of crimes against women sixty years apart framed as a ghost story. Set in the wilds of rural Northern Ireland, a grim, isolated farmhouse conceals an appalling (though sadly not unbelievable) history of sex-slavery, murder and other atrocities, its very floors and walls lined with bones.

New owners move in - a domineering, controlling husband and his mentally fragile wife Sara. It is Sara who is contacted by a previous inhabitant of the house, who turns out to be not so much a former resident as the sole survivor. As the past horrors of the farmhouse are revealed and Sara’s present-day relationship collapses into violence, she is trapped, but also in a way saved, by the ghosts in the very fabric of the house.

Terrific, sometimes terrifying, Gothic story-telling.

This could be the most aptly-titled debut crime novel of the year because it takes place over one hectic day in the London underworld where virtually everybody dies violently. A Good Day To Die by Amen Alonge [Quercus] features a multi-cultural cast who kill or are killed with guns (so many guns) and even a grenade and happily mutilate their victims with machetes in search of a valuable diamond bracelet, a bagful of drugs or just in vengeance for an ancient snub or betrayal. And betrayal does seem to be the main driving force in the operation of this very unpleasant world of drug lords, crime bosses, Russian mafiosi and corrupt policemen. These guys make Reservoir Dogs look like a meeting of Quakers. This could be the most aptly-titled debut crime novel of the year because it takes place over one hectic day in the London underworld where virtually everybody dies violently. A Good Day To Die by Amen Alonge [Quercus] features a multi-cultural cast who kill or are killed with guns (so many guns) and even a grenade and happily mutilate their victims with machetes in search of a valuable diamond bracelet, a bagful of drugs or just in vengeance for an ancient snub or betrayal. And betrayal does seem to be the main driving force in the operation of this very unpleasant world of drug lords, crime bosses, Russian mafiosi and corrupt policemen. These guys make Reservoir Dogs look like a meeting of Quakers.

The cast of characters is huge and it is often difficult to keep track of them, though the main protagonist’s backstory - he is known only as ‘Pretty Boy’- told in flashback is heart-breaking at times. Given the ridiculous level of violence throughout, however, few of the supporting cast survive but one cannot deny the power and pace of the story-telling.

If you’ve been denied a holiday in Spain recently, the odds are it wasn’t to Terra Alta in Catalonia, but if it was then don’t expect a tourist-friendly guide to the local food and drink in Even The Darkest Night by Javier Cercas [MacLehose], because it’s not that sort of bucolic crime novel.

The central crime is the ritualistic torture and murder of an elderly couple, the heads of a powerful business empire, but the focus of the book is the story of police detective Melchor Marin. The son of a murdered Barcelona prostitute who, as a youth, works as a driver for a Colombian drugs cartel, is arrested, jailed and while in prison devours Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, Marin determines to become, on release, a policeman. He not only does so (partly in the hope of finding his mother’s killer), but discovers he’s quite good at it and quickly establishes his heroic credentials when foiling a terrorist attack.

Marin is due to appear in more ‘Terra Alta’ novels and though the fact that they are written mostly in the present tense may put some people off, he is definitely a character worth keeping an eye on.

Can anything new be wrung out of the serial-killer sub-genre? American debutant crime writer Stacy Willingham has a go, and successfully so, in A Flicker in the Dark [HarperCollins].

Set around swampy Baton Rouge in Louisiana, a spree of serial-killings seems safely 20 years in the past with the killer, having pleaded guilty, serving life imprisonment. But then, wouldn’t you just know it, young women start disappearing again and it looks like a copycat is on the prowl. The central character, a female psychologist is the daughter of the incarcerated killer (though never seems to have thought to change her name) is immediately involved in the search for the copycat and, despite an unfortunate reliance on prescription drugs, finds herself acting as an accidental detective. Despite a couple of necessary suspensions of disbelief - and the fact that I guessed the identity of the killer less than halfway through - Stacy Willingham can write and she has a cracking story to tell. Set around swampy Baton Rouge in Louisiana, a spree of serial-killings seems safely 20 years in the past with the killer, having pleaded guilty, serving life imprisonment. But then, wouldn’t you just know it, young women start disappearing again and it looks like a copycat is on the prowl. The central character, a female psychologist is the daughter of the incarcerated killer (though never seems to have thought to change her name) is immediately involved in the search for the copycat and, despite an unfortunate reliance on prescription drugs, finds herself acting as an accidental detective. Despite a couple of necessary suspensions of disbelief - and the fact that I guessed the identity of the killer less than halfway through - Stacy Willingham can write and she has a cracking story to tell.

The last time I checked, climbing a mountain in the Himalayas (with or without oxygen) did not feature on my Bucket List and after reading Breathless by Amy McCulloch [Michael Joseph], I have absolutely no desire to add it even as an afterthought.

To attempt to climb the fourteen highest mountains in the world in a single year without oxygen is the sort of challenge which surely attracts the borderline crazy. In the case of the expedition in Breathless, which includes the inexperienced climber and would-be ‘adventure journalist’ Cecily Wong, it also attracts the homicidal. Written by a Canadian mountaineer of some repute, though the modern term seems to be the quaintly Victorian ‘alpinist’, the rigours of a high altitude ascent are meticulously described, down to the need to recharge electronic equipment so the climbers can keep up with their emails and Instagram accounts. There are also severe warnings about High Altitude Pulmonary and Cerebral Edemas, which only strengthen my resolve that any activities on my Bucket List will take place at sea level. To attempt to climb the fourteen highest mountains in the world in a single year without oxygen is the sort of challenge which surely attracts the borderline crazy. In the case of the expedition in Breathless, which includes the inexperienced climber and would-be ‘adventure journalist’ Cecily Wong, it also attracts the homicidal. Written by a Canadian mountaineer of some repute, though the modern term seems to be the quaintly Victorian ‘alpinist’, the rigours of a high altitude ascent are meticulously described, down to the need to recharge electronic equipment so the climbers can keep up with their emails and Instagram accounts. There are also severe warnings about High Altitude Pulmonary and Cerebral Edemas, which only strengthen my resolve that any activities on my Bucket List will take place at sea level.

I did learn other things: that ‘summit’ can now be used as a verb when reaching the top of a mountain (as in ‘I summit’, ‘she summits’, ‘they summited’) and also that Breathless is a tale of high adventure which leaves the reader, not to put too fine a point on it, breathless.

Thomas Mogford has a clutch of excellent crime novels featuring private investigator Spike Sanguinetti and tantalising Mediterranean settings to his credit, but now, as T.L. Mogford he has turned to the adventure novel with The Plant Hunter [Welbeck Fiction]. There is a gentler, slightly Victorian feel to the book, which is perfect for its subject matter as it is set in the 1860s at the height of the Victorian passion for rare plants, which was clearly a cut-throat business when it came to finding them, growing them and selling them for fashionably high prices. Thomas Mogford has a clutch of excellent crime novels featuring private investigator Spike Sanguinetti and tantalising Mediterranean settings to his credit, but now, as T.L. Mogford he has turned to the adventure novel with The Plant Hunter [Welbeck Fiction]. There is a gentler, slightly Victorian feel to the book, which is perfect for its subject matter as it is set in the 1860s at the height of the Victorian passion for rare plants, which was clearly a cut-throat business when it came to finding them, growing them and selling them for fashionably high prices.

In The Plant Hunters, our hero, a young horticulturist, come into possession of a map leading to - in China - a source of the fabled ‘Icicle trees’ and after some skull-duggery in (a wonderfully evoked) London, he sets off to hunt that particular plant. There is a murder, eventually resolved in Shanghai, and a lengthy and dangerous journey to the Yangtze valley - with a splash of romance - before the pleasingly satisfactory ending. A refreshing change from contemporary mayhem, with echoes of Stevenson and Verne, which can’t be bad.

Anyone who can write a hundred, or possibly more by now, short stories as well as more than forty full-length novels in a fifty year crime-writing career fully deserves the accolade of a new anthology and that’s exactly what Peter Lovesey gets with the publication of Reader, I Buried Them [Sphere].

In among the many treats included are advice on what to do if you meet one half of Ellery Queen in a lift, a warning never to underestimate a romantic novelist and helpful health and safety rules for booksellers unpacking a crate-load of Agatha Christie first editions. Enjoy!

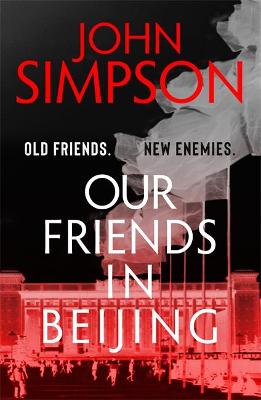

John Simpson is one of the BBC’s most distinguished television reporters when it comes to foreign affairs. In Our Friends in Beijing [John Murray], which for legal reasons I missed when it appeared last year but is now out in paperback, his hero (and alter ego?) Jon Swift is a less distinguished, rather prickly veteran television journalist involved in a modern piece of Chinese skullduggery with echoes of his time reporting on events in Tiananmen Square back in 1989. reporters when it comes to foreign affairs. In Our Friends in Beijing [John Murray], which for legal reasons I missed when it appeared last year but is now out in paperback, his hero (and alter ego?) Jon Swift is a less distinguished, rather prickly veteran television journalist involved in a modern piece of Chinese skullduggery with echoes of his time reporting on events in Tiananmen Square back in 1989.

Swift is initially drawn into events in Oxford where he naively agrees to pass on a coded message for an old Chinese contact (now a big shot in Chinese politics). This alone should have made Swift smell a rat, but off he goes to Beijing, thinking there may be a story in it. (At this point there are numerous mentions of the code word ‘Excalibur’ being a Monty Python reference, which baffled me as I thought I knew my Python.)

John Simpson is known and admired for his pieces to camera and that is exactly the style which his narrator hero adopts. But Swift isn’t Simpson and one doesn’t quite trust him to stick to the point and his asides to the reader - Tony Blair, our esteemed prime minister - remember him? - often grate. But when he is not breaking the fourth wall, he gives us a fascinating portrait of life behind what used to be called The Bamboo Curtain, though only old China hands like Jon Swift probably still use that expression.

Best Title Ever

The title I wish I’d thought of belongs to a Netflix series which gloriously catalogues every cliché and trope in the ‘domestic noir’ playbook, and deliberately so, making The Woman In The House Across The Street From The Girl In The Window my current binge-watch guilty pleasure.

The main character is a sommelier of Olympic standard and the outcome of take-your-daughter-to-work-day (in a prison full of serial killers) is stunningly dark. There’s also a clue to the identity of the murderer in that very title. Who said Americans couldn’t do irony?

Toodles!

The Ripster

|