|

Back in the Groove

After twenty months of enforced social distancing (that’s our excuse and we’re sticking to it) Shots’ very own avengers were able to assemble after an editorial hot-desking session in their new ‘pop-up’ offices, The Rose & Crown in London’s Piccadilly.

Whilst it was a delight to catch up face-to-face with Mike Stotter and Ayo Onatade, the real purpose of the evening was to attend the sumptuous launch party thrown by Felix Francis for his new novel Iced [Simon & Schuster].

A new Dick Francis novel was always celebrated with the first major party of the publishing ‘season’ and his son Felix has continued that noble tradition. He will be continuing another, he revealed, in that his next book will bring back one of his father’s best-loved characters, Sid Halley.

Felix’s publisher made special mention at the event, of the review of Iced by Tim Head in Shots, and certainly the book was in great demand on the night.

Any launch where copies of the book sell out before the wine runs out must surely be judged a success.

With Great Influence...

I am well aware that being ‘an influencer’ (as the young people say) comes with great responsibility. I am constantly reminded of this by the number or correspondents who complain that reading this column puts a strain on their bank balance by tempting them into buying books of which they had not been previously aware. Still, it is rewarding when those whose reading habits I have influenced get in touch, even if they are writing from the bankruptcy courts or a debtors’ prison.

One heart-warming story came to light recently when a reader, having noted my admiration for the story-telling powers of the author Nevil Shute (1899-1960), got in touch to say they had just ‘rediscovered’ with much pleasure Shute’s 1950 novel A Town Like Alice.

In reply, I encourage my correspondent to try some other Shute titles, including the remarkable What Happened To The Corbetts and to our mutual pleasure, my reader reported that he had almost immediately found a 1958 hardback edition, modestly priced, in a second-hand bookshop on the north Norfolk coast.

I call this book remarkable simply because it is, and yet strangely it remains one of Shute’s lesser-known titles these days. It is a simple story of a young family adapting to and learning to survive the devastating effect of a mass air raid on Southampton. The enemy dropping bombs on civilian targets is never identified and to many at the time it must have seemed like a piece of horrific science fiction rather than a portent of what was to come. Because - remarkably - the book was written in 1938 and first published in April 1939, six months before WWII broke out and air raids became reality rather than fiction, Southampton itself being badly ‘blitzed’ in November 1940.

Nevil Shute, an aeronautical engineer, was more aware than most of what damage aerial bombing could produce and undoubtedly saw the novel as a warning to the authorities to sharpen up their Air Raid Precaution provision. His publishers Heinemann certainly did their bit in 1940, producing a special edition of 1,000 copies for free distribution to ARP wardens.

Always keen to hear from those influenced (or found under the influence) by this column, readers are reminded that they can contact me by the traditional method of sending an owl to Ripster Hall, or by something called ‘electronic mail’ care of the editor of this magazine at shotseditor@yahoo.co.uk

Robert Richardson, R.I.P.

Robert Richardson, who had the dubious but unique honour to be chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association twice, has died, aged 80 from complications arising from Lewy Body dementia. His debut crime novel The Latimer Mercy won the CWA’s John Creasey Award in 1985 and he was a stalwart supporter of the organisation from then until his death, although his last novel appeared in 1997.

I first met Robert in 1990 when we were among a gaggle of new crime writers whose books were just appearing in paperback, being promoted by Hatchards bookshops.

Robert can be spotted on the far right of this line-up, taking cover behind Simon Brett and John Malcolm.

I cannot pretend to have known him well, though we did appear on the same public platforms in various libraries in his adopted county of Hertfordshire thirty years ago. A journalist from leaving school to his second ‘retirement’ as a sub-editor on the Guardian at the age of 74, Robert, when a sub-editor on the new broadsheet newspaper The Independent in the early 1990s, was teased mercilessly at CWA meetings because the paper refused publicly to review genre fiction.

Although I did not seen him in the last 25 years, I do have one abiding memory of Robert as he was the person who recommended (nay, insisted) that I read the works of Robert Player, the pen-name of architect Robert Furneaux Jordan (1905-1978) who wrote five crime novels set mostly in Victorian and Edwardian England. I took his advice and tracked down a copy of Oh! Where are Bloody Mary’s Earrings? (I still have it) - and then immediately sought out Player’s other titles, including the wonderful Let’s Talk of Graves, of Worms, of Epitaphs.

It was a terrific recommendation as the Player books are excellent, though I’ve met few people who have read them, and I will always be grateful to Robert Richardson for making it.

Tiger, Tiger

In the always readable Times Crime Club newsletter last month, former Home Secretary and noted memoirist Alan Johnson wrote about his five favourite crime novels whilst promoting his own first venture into the genre with The Late Train to Gypsy Hill.

Having mentioned Bleak House (1852), The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892), Maigret at Picratt's (1951) and In Cold Blood (1966) he admits that he came to prefer Margery Allingham over Agatha Christie and in particular The Tiger in the Smoke (1952) with its ‘principle baddie, the albino gang leader Tiddy Doll.’

Now that’s odd because I always thought the principle baddie in that book was the knife-wielding psychopath Jack Havoc, the ‘tiger’ of the title. But what do I know?

Agatha? Surely not.

The reissue this month by Dean Street Press of the 1930 mystery The Invisible Host is bound to ruffle the feathers of many in the GA (Golden Age) community, not only because it is a rare book back in print but because of the influence it might have had on Agatha Christie.

Written by a young married couple of Louisiana journalists, Gwen Bristow (1903-1980) and Bruce Manning (1902-1965), The Invisible Host was turned into a Broadway play and then filmed in 1934 as The Ninth Guest.

.png)

The plot involves eight (not ten) guests being invited to an art deco penthouse in New Orleans (not an island off the coast of Devon) to be greeted not by their anonymous host but only a spooky recorded voice, a sure portent of murderous doom. If any of this sounds remotely familiar as the plot of a book which I am not allowed to identify by its first two titles and therefore will stick to its most recent, And Then There Were None, which appeared in 1939, then now is the time, thanks to Dean Street, to make the comparison.

The Introduction to the reissue notes, perhaps with tongue-in-cheek, states that Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning, who had moved to Hollywood by 1940, never attempted to sue Agatha Christie for plagiarism when the great Dame’s masterpiece was published in America. Perhaps they couldn’t find a lawyer in Hollywood.

Agatha: Howshedunnit

If asked which was the most popular method of murder in Agatha Christie’s impressive output of crime fiction, my bet is that the most popular answer would be poisoning, most likely by using arsenic. I may very well suggest this to Richard Osman as a category for Pointless.

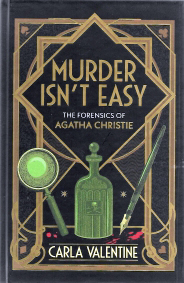

In fact, only 13 victims in her entire canon were dispatched that way. More than three times that number (42 to be precise) of characters became corpses thanks to gunshots. This is just one of the many fascinating things I learned from reading the detailed and deliciously gruesome Murder Isn’t Easy by Carla Valentine (Sphere), a comprehensive study of the forensics in Christie’s fiction, as well as a fascinating history of forensic science itself.

Compared to Carla Valentine, I have not read much Agatha Christie - she seems to have read everything - and so I was unaware of just how on the ball Agatha was when it came to forensics, from fingerprinting (relatively new when she started writing) to post mortems. Similarly, not having read The Secret Adversary, her second novel from 1922, I had missed the character of Julius P. Hersheimer who carries an automatic pistol which he has nicknamed ‘Little Willie’ and, yes, there is the double entendre when an excitable Hersheimer exclaims that his ‘Little Willie is just hopping to go off’!

For the completist there is a most useful appendix listing every Christie novel and the methods of murder employed; some sixteen different ones from gunshot to poison, electrocution to hanging, burning, strangling, drowning and being chopped with an axe. Not surprisingly, the 1939 novel which dare not speak its name (set on an island off the Devon coast) scores the most, with six (at least) different methods of dispatch.

Interleaved with her study of Christie’s fiction, Valentine provides numerous fascinating nuggets on famous ‘true’ crimes and the history of forensics. Although this is not a subject I am particularly familiar with, I did recognise such names as Robert Churchill and Bernard Spilsbury and, again, learned much along the way, including the facts that the earliest solving of a murder by ballistic comparison (of a musket ball and wadding) was in 1784 and the first crime, though not a murder, to be solved by comparing spent bullets was a result for the Bow Street Runners in 1835.

Dedicated fans of Agatha Christie and those with a deep interest in the mechanics of murder and its detection - and I do not claim to be in either camp - will find much to enjoy (though that’s perhaps not the right word) in Carla Valentine’s accessible and entertaining book. Her grasp of the Christie canon seems comprehensive and I have no doubts whatsoever about her credentials when it comes to writing about dead people.

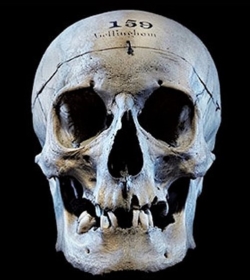

I met Carla some years ago, in the pathology museum where she works, and she took great delight in showing me the skull of James Bellingham, the ‘angry businessman’ who shot the Rt.Hon. Spencer Percival in 1812. The only successful assassination of a British Prime Minister.

So far.

|

|

BOOKS OF THE MONTH

Box 88 is a covert intelligence organization - a sort of International Rescue for the western democracies - with seemingly endless resources so their agents don’t have to resort to fiddling their expenses. Recruited virtually from (public) school, Lachlan Kite is, by 2020, a senior director of Box 88. And that’s all you really need to know to enjoy Judas 62 [HarperCollins] the cracking new spy thriller by Charles Cumming.

A ‘Judas list’ is a vengeful wish list of enemies of Russian intelligence who have been targeted for assassination and one of the names on it (at number 62) is Peter Galvin, the name he used on one of his first assignment as a trainee agent in 1993. As the story unfolds, mostly in flashback to that ill-fated first mission, we see, in more ways than one, the emergence of the ‘perfect spy’ and yet, with a knowing nod to Le Carré, Kite acknowledges that he is far from the perfect spy, as he allows his private life to impinge, quite literally, on his debut undercover mission.

The overwhelming sense of suspicion in post-communist Russia is superbly done, proving that little changes, because it isn’t paranoia; they really are watching and following you.

Readers of the new Jack Reacher adventure Better Off Dead [Bantam] by Lee and Andrew Child, may experience a shock, or at least mild palpitations, at the end of Chapter One, but they should not worry, Reacher isn’t dead - and that’s not really a spoiler given there is a fair amount of rugged, and quite ruthless, violent justice to be dispensed by our hero in the following three hundred pages.

Reacher, the ultimate Homeric action hero wandering the world (or at least the USA) righting wrongs as he goes, finds himself in Arizona where, at a sun-baked crossroads, he comes to the aid of a woman seemingly injured in a car accident. Appearances are deceptive though, for the woman is neither injured nor the victim of an accident, but is laying a trap for a pair of hitmen on her trail, hitmen she dispatches with frightening professionalism, impressing the watching Reacher who decides this is a woman in trouble, but one well worth siding with.

And we’re off on another action-packed, two-fisted tale involving terrorism, chemical weapons, and a mysterious baddy who has picked a remote desert ghost down to set up a company manufacturing airline meals. Suspicious? Damn right.

Is contemporary German crime fiction undervalued in this country? Probably. Certainly compared to Scandinavian crime fiction it is and despite its prestigious Krimi Preis awarded annually since the 1980s, most British readers, if asked to name a fictional German detective would probably say ‘Bernie Gunther’. There is now, however, a female police detective, Louise Boni, as created by Oliver Bottini (the winner of numerous Krimi awards), who really should be on every crime fiction fans’ to-be-read pile.

Night Hunters, out now from MacLehose Press, is Detective Chief Inspector Boni’s fourth fictional case and is set near Freiburg in the Black Forest and across the Rhine in Colmar in neighbouring France, which is important not only to the plot but also because Boni is half-French. A young female student from a well-off family goes missing and is terribly abused, only to be found by a disturbed teenage boy, a loner with a violent father, who is himself murdered as the abductors cover their tracks. Breaking all the rules of police procedure as fictional detectives always do, though with good reason this time, Boni finds the missing girl and take on the ‘night hunters’.

If I have a criticism, it is that there are perhaps too many references back to the first three books in the series as Boni’s history is fleshed out and I also had to look up Gugelkopf (which would be a challenge on the German version of Bake Off if there is one) and Cevapcici (grilled Serbian sausage meat) - but that’s my fault.

Along the way, Bottini gives the reader a fascinating glimpse of some unsavoury sides of German society, including the fact that fans of the national football team refer to their Mexican opponents as ‘dwarves’, but importantly, a heroine well-worth cheering for.

I once got into trouble with Minette Walters for describing one of her books as prime example of southern Home Counties noir, a classification I had just made up. I am confident though that I can use the term Outback Noir for a new crime novel from Australia, as the term is already in use there thanks to best-selling thrillers from Jane Harper, Chris Hammer and a growing number of others.

The Stoning [MacLehose] is, I think, a first crime novel by Peter Papathanasiou and a mightily impressive one it is too. It adopts one of the fast-becoming standard tropes of outback noir, where the investigator (police detective or journalist) is sent to a small, declining town in the back of beyond with which he had some previously, hopefully forgotten, connection, where something nasty has happened. And in The Stoning, something very nasty has happened to the local schoolteacher - the clue is in the title - of the unsavoury town of Cobb, where even the kangaroos have a police record for violence.

Detective Sergeant George Manolis - a cop who has only fired his gun twice in his entire career - is sent to the dust hole that is Cobb, although the town is not as he remembers it. Not only has it declined in prosperity, is now ravaged by alcohol and drugs and relations with the local indigenous community are at an all-time low, but on its outskirts there is a detention centre where illegal immigrants, asylum seekers, refugees and those without proper papers are corralled. When the local schoolteacher is stoned to death, Muslim detainees are instantly suspected by the xenophobic townsfolk and revenge, or at least public outrage, seem on the cards.

Manolis discovers that conditions in the camp, known locally as ‘the brown house’, are something Australia should be ashamed of and the author pulls no punches expressing his outrage at the situation. Papathanasiou also describes the emptiness of life in the outback - the wildlife, the heat and the hero being vast distances away from back-up, or a hospital, or even a mobile phone signal - with a grim savagery. Powerful, dramatic stuff.

Comedy crime writing is difficult, so they tell me, and is one of the smallest of sub-genres in the broad church of crime fiction. There have, however, been some notable practitioners of the dark art, ranging from the satirical to the absurdist, the farcical to the Sit Com, including the divine Sarah Caudwell, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Peter Guttridge, Colin Bateman, Carl Hiaasen, Kinky Friedman, Christopher Brookmyre, Simon Brett and Malcolm Pryce - and those are only the ones I’ve had a drink with.

Once Upon A Crime by Fergus Craig [Sphere] is a debut toe-dip into the shark-infested custard that is comic crime and seems determined to try every avenue possible in order to raise a laugh. The setting is Exeter - though it falls short of the mean streets of Malcolm Pryce’s Aberystwyth and the surreal daftness of Jasper Fforde’s Swindon - and the central character, a police detective called Roger LeCarre, is a truly horrible character who seems deliberately and arrogantly stupid. As the police force he belongs to is Devon & Cornwall, there are lots of gags about local rivalries and ‘chasing the triads’ out of the county across the border into Dorset, and some of them are genuinely funny but they get submerged in the need to make everything into a joke or smart remark, and then explain why it is funny, or smart.

There are also lots, and I do mean lots, of references to people and things which may not be obviously comic - Bradley Walsh for instance (OK, fair enough), the listing of the alcohol-by-volume of various beers on a pub bar, and the Kia Ceed (sic).

This shotgun approach quickly becomes exhausting, even when leavened by gobbets of extraneous information as if lifted directly from a tourist guide or the Good Beer Guide (J.K. Rowling even gets a passing mention as an alumna of Exeter University). But the main problem is the over-the-top character of Roger LeCarre, who is so obnoxious and determinedly obtuse that it’s impossible to take him humorously let alone seriously. His method of breaking the news of the murder of her son to a sexy mother is shown in all its gruesome bad taste, but it’s a scene which could have been darkly brilliant had it, say, been played by Ricky Gervais in his David Brent persona. When it comes to genuinely stupid policemen being promoted beyond their capabilities for comic effect, then Wilfred Dover in the books of Joyce Porter over fifty years ago is still good template.(Go on, Google them.) But then, what do I know?

Better Late...

For legal reasons I missed Girl A by debut author Abigail Dean [HarperCollins] when it appeared earlier this year, however it is now out in paperback and I’ve managed to catch up with one of the most gripping, and disturbing, thrillers of the year. For legal reasons I missed Girl A by debut author Abigail Dean [HarperCollins] when it appeared earlier this year, however it is now out in paperback and I’ve managed to catch up with one of the most gripping, and disturbing, thrillers of the year.

I say disturbing because the book’s underlying plot is all too frighteningly credible. In an isolated house on northern moors, a family cuts itself off from the local community and indeed the rest of the world, on the orders of the deluded father, a religious nut-job who seems determined to breed his own, captive congregation. And I do mean captive, as coercive control, sensory deprivation and then physical restraints make sure his wife and young family are not going anywhere. When the eldest daughter escapes and her numerous siblings (no spoilers!) are rescued, the press have a field day with the ‘House of Horrors’ and the children are sent to foster homes and designated ‘Girl A’, ‘Boy A’, ‘Girl B’ and so on to protect their anonymity.

Fast forward fifteen years and Girl A - the one who escaped and fetched help - has to face up to being executor to her mother’s will and disposing of the house of horror, for which she needs the agreement of the surviving children, all of whom are coping with personal demons following their appalling childhood. In her quest, Girl A relives her own nightmare experience and is strangely drawn back to the house on the moor.

The narrative of Girl A is told using flashbacks and cut-aways to reveal what happened in the house and how the children subsequently survived. It is not a straight-forward technique which requires concentration from the reader and the author is brave to try it. The result is powerful and absolutely harrowing.

Something, something, something...Complete

I decided some time ago that my crime fiction education was incomplete because I simply had not read enough Peter Dickinson (1927-2015), the multiple award-winning (two Gold Daggers in successive years) author of crime novels and young adult fiction (a brace of Carnegie Medals) whose detective stories were often compared in style and humour to those of Michael Innes. If the names Peter Dickinson and Michael Innes mean nothing, then shame on you.

To give you a flavour, The Seals (1970), Dickinson’s third novel to feature Detective Superintendent James Pibble, is set on a remote island in the Hebrides which is the home of an order of distinctly strange monks. In his Author’s Note prior to Chapter One, Dickinson warns the reader: All the religion in this book is entirely imaginary, and has no reference to any living God....

Stay safe and keep reading,

Toodles!

The Ripster.

|