| 2020: The Year (and the people) Just Gone

Few will mourn the passing of the year 2020, though many will lament the passing of some fine crime writers.

My annual survey of SHOTS which, despite the dearth of publishers’ parties, free lunches and book launches, has maintained a creditable commentary on the UK crime and thriller scene in 2020, with 171 individual book reviews, 16 feature items, 251 blog postings and this particular column covering at least 303 authors and their books.

Publishing in general was hit by the pandemic which resulted in the staff of many firms operating from home, cut off from their filing cabinets, supplies of review copies and their favourite restaurants. Libraries and bookshops were severely affected as were the book wholesalers who supply them. Many titles were deferred for months, sometimes a year, others slipped out with none of the fanfare they deserved. In sheer volume, though, it seems to have been a bumper year for crime and thriller fiction.

Here I must declare my usual caveats that (a) I do not claim my database is comprehensive, (b) the workings of many publicity departments has been (understandably) erratic this year, (c) this column is still on the Naughty Step of some publishers (they know who they are), (d) my arithmetic is suspect at best and after a festive case of Amarone, not to be trusted.

However, I estimate that there were 634 new crime and thriller titles published in the UK in 2020, which is roughly one every 13 hours 48 minutes. These were books (not eBooks) published by commercial publishers (i.e. not self-published) for the first time in the UK.

Interestingly, though perhaps not surprisingly given the popularity (among editors and agents) of the domestic noir sub-genre, the number of female authors continues to rise. Traditionally, women writers have been responsible for just over a third of all crime fiction titles (which, of course, is not the same as sales,nor, indeed, readers) but in 2015 this proportion rose to 37%, then 45% in 2019 and 47% in 2020.

And so, unlike the rest of the country, especially now Brexit has been well-and-truly done, crime fiction seems in rude health, but sadly, cruel 2020 has claimed some notable victims.

The deaths of thriller writer Alan Williams and American mystery writer Walter Satterthwait, although neither were unexpected, were both a personal loss for me as I knew them and had the pleasure of editing new editions of some of their novels.

The death of Jill Paton Walsh was a particular blow to the Dorothy L. Sayers Society who will be forever grateful for her ‘continuation’ novels featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the passing of John Le Carré produced a host of tributes from around the world and prompted his many fans into an ongoing ‘favourite title’ meme. (Mine is A Perfect Spy if anyone is remotely interested.)

And in early December, sad tidings from Edinburgh reporting the death of Alanna Knight, MBE at the age of 97, after a writing life of more than fifty years and over sixty books.

A successful writer of romantic fiction before she turned to crime in 1988 with the first in her best-known series of mysteries featuring Victorian detective Inspector Faro, Alanna completed six novels whilst in her nineties, one of which, Murder at the World’s Edge, will be published posthumously in May by Alison & Busby. On hearing of her death, former Edinburgh neighbour Ian Rankin described her as ‘a stalwart of the crime-writing scene’ and, given that she was at work on a new novel at the time, that ‘she died with her boots on’.

Q: When will there be good news?

A: Now

At last, at the fag-end of the plague year, there was some good news. The award-winning crime writer Andrew Taylor, the most popular panellist (because he knows things) in CrimeFest’s iconic quiz I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Cluedo, has need of a bigger trophy cabinet having received the Historical Writers’ Association award for best novel of 2020 for The King’s Evil.

For fans of Andrew’s ‘Marwood and Cat’ series set in Restoration London there is more good news. A fifth instalment, The Royal Secret, is due to be published in April by Harper Collins.

And yet more good news from HarperCollins who, in June, will publish the collected Short Stories of Reginald Hill (Vol. I).

Reg Hill (1936-2012) and I became good friends from the time I joined the legendary Collins Crime Club with my first novel in 1988.

As he lived at the diagonally opposite end of England from me, we saw each other only occasionally at conventions and festivals in London, or Manchester or Nottingham, but for more than twenty years we were, in those pre-email days, pen-pals and I still have many of Reg’s letters (often illustrated with pictures of cats) and postcards, usually featuring gloomy statues of stoic Ancient Greeks. His correspondence was always insightful and screamingly funny, with never a bad word about anyone except Scandinavians.

Initially, it was unusual

There was a time when the use of an author’s initials instead of their given first names was a talking point and a distinctive promotional tool, as, once encountered, few readers would forget such famous names as J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, P.D. James or J.R. Hartley.

Over the past couple of years, however, it seems to becoming the norm rather than the exception in crime fiction – for other genres I cannot speak – and I for one am finding this rather impersonal and not a little confusing. Among the current crop, several of whom I have met and found charming as well as talented, are: A. K. Benedict, B.A. Paris, S.K. Sharp, M.W. Craven, W.C. Ryan, M.J. Hyland, A.K. Turner (there may be two of them), T.F. Muir, M.K. Hill, T.M. Logan, C.J. Box, K.J. Maitland, S.A. Cosby, M.J. Arlidge, C.J. Tudor (see Books of the Month), C.L.Taylor, L.C. Tyler, V.L. Valentine,, T.A. Wilberg, D.K. Fields and R.J. Bailey (who has also used the names Reno Smith and Deke Thornton).

Taken to the extreme it could perhaps be a useful piece of re-branding, should an author fancy a new identity. Who could fail to be tempted by a new novel from K.E.N. Bruen, for instance? But overall, life was so much simpler when all one had to worry about was who the hell is B.Traven?

Highly Recommended

They always say, or they used to, that personal, word-of-mouth recommendation of a book is worth more than paid-for advertising, though I suspect the saying originated among publishers who had just had their promotional budgets slashed.

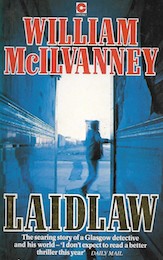

In the early days of my crime-writing life, however, I do remember being personally recommended a particular title by two people within a few days of each other, in the same week back in 1988. The book was the magnificent Laidlaw by William McIlvanney which, arguably, gave birth to the ‘Tartan Noir’ school of crime fiction. Not surprisingly, the two people who pressed this title on me (which I immediately sought out and purchased) were both Scots.

One was Val McDermid, whose forceful enthusiasm for the book – over a couple of pints in The Two Chairmen in Soho as I remember – was such that I was convinced that my career would be over before it had started if I did not read it.

The other was George Thaw, then the books editor of The Daily Mirror and a near-neighbour out in the wilds of East Anglia as well as a fellow commuter. On those daily train journeys with George, he constantly tested my knowledge of the genre and shared his memories, often affectionate but occasionally libellous, of some of the biggest names in the business.

I will always be grateful that he steered me to many good writers – Lindsey Davis was one – but especially William McIlvanney. A couple of years later, I returned the favour by recommending to him the debut novel of Minette Walters, even lending him my first edition of The Ice House, which, come to think of it, I never got back.

All this came to mind recently when I heard that McIlvanney (1936-2015) had left, on his death, the bare bones of a fourth novel featuring his influential detective Laidlaw and that the task of completing it had fallen to Ian Rankin, surely the perfect author to fill both William McIlvanney’s and Jack Laidlaw’s boots.

When The Dark Remains by the dream team of McIlvanney & Rankin, is published in September by Canongate, I will make a pilgrimage to The Two Chairmen to drink its health. If, that is, I am allowed. Soho will probably be in Tier 6 by then, which will have given me time to re-read the entire Laidlaw trilogy, reissued by Canongate in 2020 in covers which, laid end to end give a panorama of Laidlaw’s Glasgow beat.

Cold Wars

Derek Lambert (1929-2001) was a former foreign correspondent, who often used his assignments abroad as background for a raft of best-selling Cold War thrillers in the 1970s, but under the name Richard Falkirk he also penned a series of historical mysteries set in Regency England, featuring Edmund Blackstone, describe by one reviewer as ‘the Bond of the Bow Street Runners’. In 1971 and ’72, he used the Falkirk name for a pair of contemporary spy thrillers, the first of which, The Chill Factor, set in Iceland, is now reissued by HarperCollins.

A disgraced British agent (after an embarrassing ‘honey trap’ incident in Moscow) is invited to Iceland by the Americans, who had a military base there then, to uncover a Russian spy ring. Our hero, who adopts the personality of a hard-drinking, cynical journalist, but is in fact a keen ornithologist (possibly in homage to the original ‘James Bond’?) does not inspire too much confidence as he follows the trail of clues laid out for him, but fortunately has access to cars, planes and boats which allow him to cover a lot of territory and, of course, his animal magnetism is irresistible to women, especially a statuesque Icelandic air stewardess. Along the way he indulges in a running commentary on all things Icelandic in the manner you might expect from any hard-drinking foreign correspondent perched on a bar stool.

It is this slightly patronising attitude to Iceland (the first club listed in our hero’s Reykjavik guide book is ‘Alcoholics Anonymous’) which seems to get under the skin of native crime-writer Ragnar Jónasson who has contributed the Introduction to The Chill Factor, even though it was published before he was born. (Did he have to point that out?)

Ragnar admits that in 1971, Iceland was ‘unchartered territory’ for the contemporary thriller, despite, as he points out, Desmond Bagley’s far superior Running Blind appearing the year before – though he omits Alan Williams’ The Brotherhood which was published in 1968. And despite the misgivings of a translator, who feared that some of Falkirk’s observations on Iceland may cause offence when the book was published in Icelandic in 1972 and made the local newspapers (as did Desmond Bagley) under the headline A foreign author chooses Iceland as a setting.

Icelanders seem to be a much more sensitive bunch than I realised, in fact there is a saying, I am told, in Iceland which translates as "You're a latte-sipping woollen scarf" which may, or may not, apply here. I can, however, understand their niggles of resentment, having had to read numerous ‘cosy’ crime novels written by Americans but set in an England designed by Walt Disney and narrated by Dick Van Dyke. The Chill Factor is not Derek Lambert’s best thriller and it is certainly not the best British thriller of 1971, but it is a workmanlike example of a genre that was incredibly popular and authors were constantly on the look-out for new and exotic locations at a time when readers (unlike foreign correspondents) did not travel that widely.

Trades Description

The latest former soldier to join the ranks of (no doubt) bestselling authors, which include Andy McNab, Chris Ryan and Ollie Ollerton, is Kim Hughes, a bomb-disposal expert of some renown (he was awarded the George Cross after service in Afghanistan) with a debut novel out now from Simon & Schuster.

I am no expert on this particular sub-genre of thrillers, though I recognise their popularity among mostly male readers. The only thing which bothers me about Operation Certain Death is that it is billed as a ‘Dom Riley’ thriller, Dom Riley being a bomb-disposal expert and the first-person narrator, and yet comes with an appendix offering an extract from the forthcoming Operation Black Key in which Sergeant Dom Riley returns. Therefore the title of his first outing is clearly misleading.

Postbag

Following my selection of Kind Hearts and Coronets as the reissue of the year, I am informed that in June, the Borough Press will publish How To Kill Your Family by Bella Mackie, which is ‘based on’ the famous Ealing comedy. Coincidence? Probably.

*

I have been chided, nay harangued, by a North American correspondent for claiming that the impressive Blacktop Wasteland was S.A. Cosby’s debut novel when in fact he already had one other published, albeit only in America. All I can say is that it was definitely the first S.A. Cosby novel I’ve read and therefore a debut for me.

Last month’s column was also viciously criticised for mis-spelling the name of Mara Timon, the author of City of Spies [Zaffre], for which apologies do of course go to Ms Timon, though in my defence I must say that for legal reasons, despite appeals to her publisher, I have not seen the book, though I am told by people who have that it is rather good.

*

Also in last month’s review of Cover Me, I picked out a 1954 paperback of The Moving Target which was billed as ‘A Lew Arless Thriller’ thinking that this must have been a mistake in the art department, as Ross Macdonald’s detective hero was surely Lew Archer, a name said to have been inspired by the firm of Spade and Archer in The Maltese Falcon.

However, a bespoke bookseller who holds a warrant to supply Ripster Hall writes to inform me that when Ross Macdonald (who was at first known as John Macdonald, though his real name was Kenneth Millar) was initially published in the UK by Cassell, the name of his detective was changed from Archer to Arless because there already was a fictional private eye called Archer on the Cassell list.

Created by Hugh Clevely (1898-1964), who also wrote as Tod Claymore, British private eye Maxwell Archer featured in seven novels and, in 1940, the film Meet Maxwell Archerbut by the early 1960s, the name Archer was clearly owned by Macdonald’s character until, that is, the film of The Moving Target came out with Paul Newman playing the role of Lew Harper.

Confused? Don’t be, just read the damn’ book.

*

Still on the subject of Cover Me - that splendid survey of vintage Pan paperbacks – I am reminded by a reader of the innovative all black Pan cover for Len Deighton’s 1970 wartime classic Bomber.

Coincidentally, another reader informs me of a proposed television adaptation of Deighton’s The Ipcress File, which is said to be set in Berlin, whilst one of my many spies within the performing arts tells me that an option has been taken on the film rights to Bomber.

*

Numerous fans of the French cop show Spiral, including one in Australia, contacted me to share the joy that the final season was to be shown on BBC4, the first episode aired on Saturday 2nd January.

*

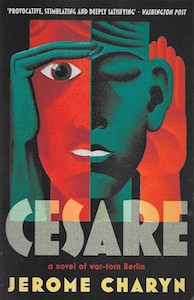

The powers-that-be at No Exit Press were, of course, far too polite to complain that last month’s column carried an illustration of the wrong cover for Jerome Charyn’s strange hypnotic wartime thriller Cesare. The impressive No Exit edition actually looks like this:

The website designer responsible for the mistake has been taken out and shot, though this should not discourage readers from trying the novel, whatever the cover.

*

And from someone looking for a particular, rather distinctive cover, comes a plea for help. Despite an extensive search, which has included all online resources, second-hand bookshops (when open) and even an appeal to the author’s literary estate, my correspondent cannot find a hardback copy of Andrew York’s 1969 thriller The Dominator published by Hutchinson to compete his collection. And from someone looking for a particular, rather distinctive cover, comes a plea for help. Despite an extensive search, which has included all online resources, second-hand bookshops (when open) and even an appeal to the author’s literary estate, my correspondent cannot find a hardback copy of Andrew York’s 1969 thriller The Dominator published by Hutchinson to compete his collection.

I have checked my own libraries and even my private Rolodex of contacts (known as the Dark Web of book dealers), but first editions of The Dominator, the fifth adventure to feature ‘Eliminator’ Jonas Wilde, would appear to be very scarce. Does anyone out there have one? I am assured that reasonable prices would be paid, even allowing for my exorbitant commission.

|

|

Books of the Month

The UK may have left Europe but thankfully Europe hasn’t left the imaginations of our best thriller writers. David Hewson has set previous novels in Spain, the Netherlands, Denmark and even the Faroe Islands, but is probably best known for his crime novels set in Italy. In The Garden of Angels [Crème de la Crime] he takes us to Venice and to areas of the city which tourists rarely venture, and, for the most part, back in time to the winter of 1943.

Mussolini has been toppled; the Germans have moved in to shore up the Fascist regime and deportations of Jews have begun in earnest. The Allies have invaded and partisans of all political persuasions are active, with each action prompting a violent reprisal. The horrors of war finally come to sleepy, isolated Venice when, just as the Nazis, their ‘Black Brigade’ lap-dogs and a turncoat ‘Jew hunter’ arrive to ‘cleanse’ the Jewish community in the famous Venetian ghetto, so too do a brother-and-sister pair of resistance fighters on the run. Their plight, and the fates of those who help them as well as hunt them is the core of the story is told in flashback through the journals a dying man bequeaths to his grandson.

Yet this is not a straightforward thriller of wartime heroic. Yes, there are heroics, sometimes in the most unlikely way, betrayals and great tragedies, proving that in such a situation, nothing is straightforward and passive inaction might just be the greatest sin. The Garden of Angels is populated by complex, superbly-drawn characters and Hewson cleverly creates sympathy for even the most unlikely ones, but the star of the show is Venice itself, its dank, cramped alleyways and faded glories. This is not the Venice of tourists sunning themselves in St Mark’s Square or on lazy gondola rides, but of an icy winter in a city under occupation where fishermen, weavers, policemen, café owners and disillusioned priests struggle to survive and do the right thing, whatever that is.

David Hewson has written some excellent thrillers. This one, by turns suspenseful and achingly sad, is one of his best.

Since it was originally announced, Graham Hurley’s latest historical thriller has not only been delayed by six months, but re-named as Last Flight To Stalingrad [Head of Zeus]. It is the fifth instalment of his ‘Wars Within’ series, which itself has been renamed ‘Spoils of War’. Whatever the series is known as, it is an outstanding achievement, a sequence of novels set in WWII with overlapping characters, in the main on the German side, each fighting a personal war of survival within the larger conflict, often at close quarters with leading figures in the Nazi hierarchy.

In Last Flight To Stalingrad, the central character is Werner Nehmann, a journalist at Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda, who is growing ever more cynical and might just be too clever for his own good, especially when he makes a copy of a compromising letter Goebbels has entrusted him to deliver. Retribution is swift and Nehmann is sent to the Russian front to write morale-boosting dispatches from Stalingrad, just as winter takes hold. As if he does not have enough to worry about, he is befriended by the Abwehr intelligence service and falls foul of the SS after witnessing one of their local atrocities, for which he eventually extracts a very bloody revenge.

Fans of the series will be pleased to know that thanks to Covid-induced delays, they have only to wait until July for the sixth instalment, Kyiv, in which I suspect we are still on the Russian front (specifically Kiev in the Ukraine). I for one cannot wait as the series proves what a fine writer Hurley is, and one totally in command of his research.

C.J. Tudor scares the hell out of me. Well, actually, she doesn’t but her books do and with The Burning Girls [Michael Joseph] has carved (probably with a serrated blade) a niche for herself as the queen of very spooky crime fiction, the sort which incorporates the tropes of the horror story and stirs in a strong flavour of the supernatural.

An urban vicar – very cunningly introduced – complete with rebellious teenage daughter, is transferred from Nottingham to a tiny rural parish of Chapel Croft in Sussex which has a history of Protestant martyrs burned by Mary Tudor. It also has a more recent tragedy to cope with, the unexplained disappearance of two young girls thirty years ago, plus an unfortunate track record when it comes to previous vicars. And then there are the ghostly apparitions of girls on fire, a plague of voodoo dolls, a hidden crypt, a haunted chapel, an old dark well (what other sort is there?) and a smattering of Satanic graffiti.

If the new parish seems to be a hellish maelstrom, just for good measure quite a few nasties follow on from the vicar’s old stomping ground and a violent conclusion is inevitable. Vengeance is mine, as someone or other once said.

Many years ago, as the crime fiction critic for that once-great newspaper the Daily Telegraph, I sent a memo to the literary editor suggesting that when a new Patricia Highsmith novel appeared, I should review it under the headline: The Talented Miss Highsmith by the Less-Talented Mr Ripley. Sadly, it was not to be, but twenty-five years on, in Highsmith’s centenary year, I get the chance to enjoy a collection of her short stories.

Under A Dark Angel’s Eye, published by Virago, which also includes two previously unknown stories, will confirm all the adjectives used to describe Highsmith’s writing: dark, disturbing, mordantly funny, gimlet-eyed, razor-sharp – I could go on. A fitting tribute to one of the greats of crime fiction.

Martin Scarsden must be the unluckiest – or luckiest – journalist in Australia, as wherever he hangs his hat, violence occurs and the past throws up skeletons faster than Ray Harryhausen used to. This is a journalist who doesn’t have to look too hard to find newsworthy stories, they fall on him from a great height. In previous outings (Scrublands and Silver) trouble has followed Chris Hammer’s hero, his newly-acquired girlfriend and stepson in rural towns in New South Wales. In Trust [Wildfire] the action moves swiftly to urban Sydney and encounters with dishonest (and in one case dead) undercover cops and very dodgy propertydevelopments including buildings with unsuitable cladding, the very thought of which is enough to make the flesh crawl.

Trust is a fine example of top-notch Australian crime fiction and there is no doubt that Chris Hammer is one of its leading lights now, but I would like to see what he could do without his alter journalist ego protagonist Scarsden. Surely, Martin has suffered enough.

Jane Harper, like Chris Hammer a former journalist, is certainly the reigning Queen of Australian crime fiction, following her award-winning debut The Dry and (I thought) the equally impressive Force of Nature. There is little doubt that her fourth novel, The Survivors [Little Brown] will be another international bestseller for her in a subgenre I have seen described as outback noir, though in The Survivors the outback is is not desert or forest scrub, but a coastal town in Tasmania, a community dependent on the sea and beach for its living and, occasionally, dying.

It is something of a slow-burner plot-wise, but as always Jane Harper excels at creating an atmospheric landscape – or in this case, seascape – for her characters to come to grips with.

Of all the Uruguayan crime writers I have read I can honestly say I have enjoyed none more than Mercedes Rosende, whose first novel to appear in English is Crocodile Tears [Bitter Lemon] and is described as a ‘blackly comic caper’.

Well, there’s certainly a caper (or two) involved, an overweight amateur detective called Ursula (who is tailing another Ursula), a dodgy lawyer, a depressive petty criminal, a total psycho and an ambitious police captain called Lionilda Lima (who never forgets she is a Capricorn), which is a heady mix and although out-loud belly-laughs may be few (or perhaps lost in translation), this is still an interesting read. In particular the scenes set in Uruguayan prisons are powerfully done. Not a lot of giggles here, but probably depressingly accurate.

Revival of the Month

To be absolutely accurate, The Conjure-Man Dies was revived three years ago in the Collins Detective Club Crime Classics imprint, an event which I somehow managed to miss completely.

However, Rudolph Fisher’s 1932 mystery, possibly the first detective novel written by an African-American, is now published as a Collins Crime Club paperback and comes with an Introduction by Stanley Ellin.

Rudolph Fisher (1897-1934) was a doctor and musician as well as a writer, though his output was sadly limited by his early death, aged 37, probably as a result of his experiments with X-rays in his medical laboratory. The Conjure-Man Dies was Fisher’s only full-length crime novel and apart from being uniquely important historically, with its Prohibition Harlem setting and cast of black characters, is really rather good.

Sherlocks

Twenty years ago this month the hot news in the crime-writing world was the announcement of the winners of the annual Sherlock Awards by the magazine Sherlock, which were to be awarded in March 2001 at a ceremony in the famous Murder One bookshop.

Uniquely, the Sherlocks were given not to authors or publishers per se, but rather to their fictional detectives, although writers were allowed to collect the prized Sherlock statuette on their behalf. The winners in 2001 are all well-known names today, which says much for the skill of their creators and the wisdom of the judge.

Inspector John Rebus, created by Ian Rankin, won in the Best Detective created by a British author category, and Detective Sergeant (as he was then) Harry Bosch, created by Michael Connelly, took the American category. The best comic detective Sherlock went to investigative journalist Jack Parlabane, who allowed Christopher Brookmyre to collect on his behalf. Similarly, Inspector Endeavour (as we had discovered) Morse, named Best Television Detective, was more than happy to allow author Colin Dexter and television producer Chris Burt to pick up the award.

A Special Sherlock was also awarded that year to June Thomson for her ‘biography’ of two very well-known fictional detectives: Holmes and Watson. The only problem there was that who would believe Sherlock when he said he’d won a Sherlock?

No Time For Non-Crime

I am often asked (well, I was once) what non-fiction I read as a respite from crime novels and thrillers during religious holidays, general strikes and lockdowns. By pure coincidence I am currently reading two excellent histories which focus on a part of northern Italy I am especially fond of, albeit a thousand years apart.

I had read and enjoyed Douglas Orgill’s thrillers The Astrid Factor and The Jasius Pursuit in my dim and distant youth, but had never, until now, tried probably his most famous title, The Gothic Line, his account of the Allied offensive in northern Italy in the Autumn of 1944. Orgill himself was a tank commander in the battle for the Gothic Line, the German defensives line which stretched from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic coast, just south of Rimini.

It is an engrossing description of a long, slogging campaign in difficult territory, of brave men from many countries (including Brazil, which I did not know), and of the significance of the battle in the overall strategy of WWII. It is tightly and clearly written and gives a fascinating insight into the planning of such a massive military operation – and the things (on both sides) which can and do go wrong. It also helps explain why, on a visit to Rimini, by chance coinciding with the anniversary of liberation by units of Greek and Canadian soldiers, I was treated to several glasses of grappaas my bad Italian accent was taken to be that of a Canadian. I had wondered why the town had been bedecked in Maple Leaf flags.

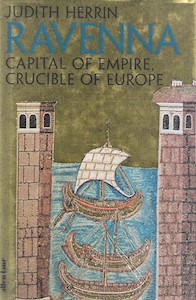

Just up the coast from Rimini is that Mecca for archaeologists Ravenna, or as Judith Herrin’s new history is titled: Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe.

A cynical Florentine café owner once told me that ‘Once a year, every schoolchild in Italy is deported to Florence’ but the next most popular destination for Italian school trips must be Ravenna, a city which can boast a history of Roman emperors, powerful early Christian bishops, Gothic kings, Byzantine warlords, Lombards, Charlemagne and the most fabulous mosaic artworks. Judith Herrin has written a fascinating history of a fascinating place, stunningly well illustrated with colour photographs which come close to giving the reader the delight of seeing them in the flesh, or rather the mosaic equivalent.

It Has To Be Better

The prospect for 2021 is one of sunlit uplands according to our trusted leaders. At least things can’t be as bad as 2020 – a year which, if filmed, would be scripted by Stephen King – can they? However, I will not tempt fate by making New Year’s Resolutions, though on my wish list would be having a book published when bookshops and libraries are actually open for business and a visa which allows me back into Europe without let or hindrance.

I will be making an effort, no doubt whilst queueing for the vaccine, to catch up on books which, for legal reasons, I missed in 2020, including titles by Robert Harris, Robert Littell and Alison Bruce, whilst looking forward to new novels from Tom Bradby, Jack Grimwood and David Peace among many, many others.

In the meantime, Happy New Year Lockdown

from Getting away With Murder,

the column proven to be 90% effective

when dealing with crime fiction.

The Ripster.

|