|

Lockdown

Reading

With

normal service totally disrupted for obvious reasons, and the number of new

crime novels being received having dried to a trickle, I have raided the

shelves of the Ripster Hall libraries for books I have been meaning to read, or

re-read, for some time.

I

think I must have been 10 or 11 when I first read Dennis Wheatley’s The

Forbidden Territory in the full knowledge that it had been written more than thirty

years before. Nowadays I fear that the junior thriller addict would bridle at

the thought of reading such an ancient story which contained no mobile phones

(indeed landline phones seem rather exotic) or computers. But I, at the time,

was thrilled by it and, on re-reading still found much to enjoy.

First

published in 1933, it was Wheatley’s first novel and an instant hit,

kick-starting a career which would see him labelled as The Prince of Thriller

Writers. It introduces his ‘Four Modern Musketeers’, a gang of rich,

aristocratic gentlemen friends lead by the Duke De Richleau, all with

impeccable credentials for being international adventurers (i.e. they are rich

and aristocratic) ready to combat crooks, black magicians, spies and, in this

case, the dreaded Bolsheviks. When one of their number goes missing in the

forbidden territory of Stalin’s Russia (forbidden because it hides secret

airfields, known at the time as ‘air parks’), the other three team up to find

and rescue him. There follows a whole series of chases, gunfights and escapes

including a dramatic sleigh ride through snowy forests and some hair-raising

flying of stolen aircraft.

In

many ways, the book is typical of the crash-bang, biff-the-baddie thrillers of

its era. What did surprise me on second reading, was the cold-blooded violence

as our heroes shoot and stab their way through a fair number of OGPU secret

policemen. There is also an extended escape scene in a crypt containing the

mummified skeletons of thousands of dead monks, worthy of Indiana Jones. No

wonder Hitchcock bought the film rights back in 1933, though a film was never

made.

Sure,

the characters are fairly cardboard and the dialogue clunky. The Jewish financier

member of these Modern Musketeers cannot say the word ‘No’ only ‘Ner’ for some

reason, and we are totally sure the American one is an American as he refers to

‘platinum blondes’, says ‘I’ve just stood on some bird’s brain box’ when he

crushes (in the crypt) a monk’s skull underfoot and ‘I guess you might have

given me the wire’ when he means ‘You could have warned me.’

But

in its day, this mixture of high living, romance, danger and fast-paced action

in a strange and very foreign setting, was clearly going to be a success. One

thing niggled me, though. I had always thought of the main character as the

Duke de Richleau and indeed that’s

what it says on the cover of this 1970 paperback (my original copy was eaten by

owls long ago), yet throughout the text he is referred to as the Duke de Reichleau. The discrepancy worried me,

but not for long.

I

have long had a soft spot for the island of Guernsey, with fond memories of

family holidays, the St Peter Port Brewery and Bucktrout & Co. wine

merchants and the experiences of the islanders during the German occupation of

1940-45 have resulted in dozens of books and memoirs over the years.

The

most intriguing is undoubtedly The Prey of An Eagle by K. M.

Bachmann, first published in 1972, which is basically four years’ worth of

(unsent) letters from a young mother living on the island to her mother, who

had been evacuated to England. They are tender, poignant and revealing about

the practice of ‘cloaking and dissembling’ – the way the islanders exchanged

war news amongst themselves. Mrs Bachmann, who frustratingly never reveals her

Christian name, comes across as a brave woman and noble soul who refused to

allow her spirit to be crushed.

After

the death of thriller writer Alan Williams in April, I promised myself I would

read the only novel of his I had missed. Dead Secret, first published in

1980, is trademark Williams. The protagonist is a pugnacious British journalist

aided by a sexy girlfriend researcher, who stumbles (or does he?) into a

conspiracy and cover-up of how a multi-national company supplied Nazi Germany

with oil during WWII. {Not a conspiracy I have ever given much credence to,

though I do believe the one about the Allies buying lenses for bomb-sights from

a well-known German optical firm.}

Our

hard-drinking journalist hero follows a trail of moles and informants from

Venice to London, Spain, Istanbul and finally East Germany, and virtually every-

where he goes there’s a murder. Could this possibly be linked to the appearance

in the book of Charles Pol, the outrageous French spy/gangster? Of course it

could. Whilst other thriller writers of that Sixties generation sought to

establish a series hero, Alan Williams invented a series villain instead, and

Charles Pol was one of the best. Or should that be worst?

Many

years ago, in the last century, at a BBC scriptwriters’ party I spotted (Sir)

Michael Palin deep in conversation with a small, balding, bespectacled man and

summoning up my courage, approached them, asking if I might ‘have a word’. Clearly

thinking I was a Monty Python fan and being natural a polite and charming man,

Mr Palin said ‘Of course you may’. He was only mildly stunned when I said ‘No,

not you, him’ and thus cornered

the small, balding, bespectacled and somewhat confused screenwriter Alan

Plater, whom I knew had been offered the job of scripting a pilot television

episode from my novel Just Another Angel.

Mr

Plater, sensing a frustrated crime writer, was disarmingly honest and admitted

he had been too busy adapting the Albert Campion story Look To The Lady by

Margery Allingham (there’s irony for you!) for the BBC. But he assured me that

his wife had read my book – and he trusted her judgement – and had said it was

very good.

Which

is a very long-winded way of saying that I have finally got around to reading a

book by Michael Palin, whose excellent travelogues simply make me jealous, and Erebus is a cracker. It is not simply the

story of a particular ship, but a study of nineteenth-century Antarctic

exploration and the ill-fated search for that elusive north-west passage

through the Canadian ice where Erebus met, along with sister ship Terror, her chilling end on the ill-fated

Franklin expedition. Knowledgeable and well-researched, this is history, plus a

real mystery, fluently told with hardly a dead parrot in sight. (Though a live

one in Tasmania is mentioned).

Regular

readers of this column – and there are some – may wonder why a charming local

history of a group of villages which have never done me any harm, near

Canterbury in Kent, Meanderings, would find its way into this column, which is

usually a reflection on matters criminal, violent and downright anti-social.

Apart

from the fact that this wonderful celebration of (peaceful) village life

produced by the Society of Sturry Villages (Sturry, Fordwich, Broad Oak,

Hersden and Westbere) is a heart-warming read, the eagle-eyed observer will

have noticed the name K. H. McIntosh as the co-editor. An introduction to the

book suggests that many of the articles in Meanderings were written by K.H. McIntosh ‘who stresses she is not an

historian’ and whilst that might be a case of false modesty, there is no

disputing that, under her pen name Catherine Aird, she is a highly-respected,

award-winning crime writer.

I

happen to know that, over the years, Kinn McIntosh has not only authored a

series of much-loved traditional British mysteries, but made a huge

contribution to local history and archaeology in her adopted county of Kent.

There is a wonderful chapter in the book about her father, Dr Robert McIntosh,

who was the local doctor in Sturry from 1946-1965, and who saw, on the front

line as it were, the introduction of the National Health Service. Working in

her father’s practice, Kinn admits to being grateful to the television series Dixon of Dock Green, shown on a Saturday

evening. So popular was the programme that almost no-one came to the Saturday

evening surgery (there were five evening surgeries per week in those days!) and

it was eventually cancelled, giving the young Kinn a free Saturday night.

I

probably bought The Second Victory when it cost 2/6d [12.5p] thinking it was

thriller about hunting Nazi war criminals hiding in the Austrian Alps

immediately after WWII. Certainly the novel, first published in 1958 and

appearing in paperback in 1961 (yes, it could take three years in those days),

has all the elements of a thriller.

The

commander of the British force occupying the small mountain town of Bad

Quellenberg sees his army driver shot dead by a rogue German soldier on day one

and it soon becomes clear that the town is sheltering the murderer. The

commander is himself viciously attacked, discovers corruption among the

civilian authorities, an embezzler who spied for the Allies, a Catholic priest with

whom he has history, and then a party of concentration camp survivors take the

law into their own hands and execute a suspected Nazi. So far so hectic a plot,

but resolution comes not in physical action, though the alpine terrain calls

out for it, but in extended soul-searching about redemption, love, loss,

forgiveness and Catholic belief.

Which

is not really surprising given that the author was Australian Morris West

(1916-1999) who trained as a monk, became a journalist and was later the

Vatican correspondent for the Daily Mail. He proved to be the author of several

incredibly popular novels almost all of which examined the role of the Roman

Catholic church in international politics. As a thriller, The Second Victory

falters just over halfway through with the introduction of several romantic

elements, the morality of divorce and an unlikely reconciliation with the

murderer from Chapter One. Yet even if it abandons its credentials as a

thriller, it is an interesting novel about faith, war and the tensions of

living under a foreign army of occupation – this time the British – and I am

surprised it has taken me over fifty years to get around to re-read it.

At

this very moment I should have

been enjoying a pre-CrimeFest break in Bologna and Modena, scouting locations

for next year’s Chianti Crime Festival. As all my plans have come to nothing I

have engaged in sulking on a grand scale and as a punishment I am working my

way through a course of Italian verb drills, and believe me, those passato prossimo reflexive verbs are a right bastardo.

Stark

Reminder

I

am indebted, yet again, to those innovative and energetic chaps over at Stark

House Publishing in America for introducing me to an author I had never come

across before, in their latest ‘double-decker’ publication featuring two

novels, Prey By Night and Rain of Terror, by Douglas Sanderson.

Ronald

Douglas Sanderson (1922-2002) was born in Kent and after wartime service in the

merchant navy and the RAF, emigrated to Canada in 1947. His first novel, an

attempt at literary fiction, appeared in 1952 but seeing the success of

American hardboiled writer Mickey Spillane, he turned to crime fiction and

thrillers. He travelled widely in America before returning to Europe to live in

Spain, but is best-known for his Montreal-set crime novels featuring private

eye Michel ‘Mike’ Garfin.

Sanderson

also published under the names Martin Brett and Malcolm Douglas and,

researching him, I thought for a moment that he must have been a remarkably

prescient writer, but that was only because I had mis-read the title of his

1961 thriller A Dum-Dum For The President as A Dum-Dum As The President. What could I have been thinking?

All

Our Yesterdays

Twenty-five

years ago, my June 1995 Crime Guide

in that once great newspaper the Daily

Telegraph featured excellent titles by six authors, all of whom I got to

know personally, some becoming, and remaining, solid friends.

Apart

from Robert B. Parker’s Walking Shadow, about which I can

remember almost nothing although I enjoyed it at the time, I have fond memories

of the latest novels by Margaret Maron, Lindsey Davis, Joan Smith and Margaret

Yorke, who was a writer of quality ‘domestic suspense’ and from whom the many

(very many) young would-be practitioners could learn a thing or two.

Yet

my prime pick of the month was the debut novel of Jeremy Cameron, Vinnie

Got Blown Away, an audacious and deeply dark story of London gang youth

told in Walthamstow patois. I had

read nothing like it before and it did, to coin a phrase, blow me away, though

not quite as violently as Vinnie. Jeremy Cameron was, I believe, employed as a

social worker in Walthamstow at the time and drove a small Skoda diesel car on

the grounds that it was the least likely vehicle to be nicked on his patch. He

subsequently retired from the Walthamstow front line and had the good sense to

move to East Anglia.

Lockdown

Blues

During

the lockdown my spirits have been boosted by the number of personal invitations

I have received from publishers, fellow writers and readers all wishing to thank

me for bringing ‘loads of wit’ (possibly misheard) to these dark times. In May

alone I was invited to five sumptuous lunches and dinners at some of London’s

most select dining venues and I was touched, nay overwhelmed, by such

generosity of spirit.

And

then I remembered that none of those venues were actually open for business and

without an operational train service I could not get to London anyway. But I am

sure neither of those factors

influenced my noble friends and colleagues who issued those invitations…

Out

here in the country we have remained relatively sheltered from shortages of

essential things. True, the absence of new episodes of The Archers and Countdown were a loss, but my wine merchant continued to deliver from

Italy and there is abundant game to shoot locally.

However,

the recent disappearance of Marmite from supermarket shelves did cause

something of a panic. The shortage is clearly due to the massive downturn in

beer production, from which the yeast extract is a tasty by-product and so I am

leading a campaign to persuade the government to allow pubs to re-open as soon

as possible so that the population may once again enjoy a decent breakfast.

I

have been informed that the excellent London family brewer Fuller, Smith and

Turner may be one step ahead of me and are opening a new chain of pubs:

From

now on, wherever you see welcoming signs such as The Garden Centre Arms, The King’s Garden Centre, The Dog and Garden

Centre, The Firkin and Garden Centre

and so on, do be sure to pop in and demand a pint of London Pride.

|

|

Books

of the Month

A few years ago that

distinguished American critic Sarah Weinman identified a trend in what might be

called domestic noir where all female protagonists would be either TSTD (Too

Stupid To Die) or ‘bat-shit crazy’, though I may have paraphrased. Given the added

trend towards unreliable narrators, the best advice to readers is to trust

no-one in a crime novel these days, especially not the person telling the

story.

The opening section of

Sharon Bolton’s The Split [Trapeze] hints that this could be a

woman-on-the-run thriller as the protagonist prepares to take refuge from an

approaching enemy in the harsh and desolate wilds of South Georgia. As she

equips herself with the basics for survival in such an extreme landscape, the

reader could be lulled into thinking this was modern-day Rogue Female,

but remember: trust no-one, especially not the main character, and the clue is

in the title as ‘The Split’ here does not refer to a fissure in the ice (she is

a researcher studying glaciers) nor to a recent bust-up with a life partner.

The bulk of the story is

told in flashbacks to a series of mysterious events and murders in Cambridge

from where the research expedition to South Georgia is launched, though the

climax and final reveal(s) takes place back on the glaciers of the South

Atlantic. There are a few moments where disbelief has to be suspended, but

Sharon Bolton ratchets up the suspense so they are hardly noticeable and her

characters – all of them (spoiler alert!) – are in turn creepy or eccentric,

but always interesting, especially the hard-drinking middle aged female police

detective Delilah, who is surely worthy of further adventures.

Readers of The Last

Wife by Karen Hamilton [Wildfire] are on firmer ground in that from the

off the narrator comes across as dangerously obsessive, not to say unhinged. I

think this falls firmly into the school of BFNN (Best Friends For Never Noir),

an extremely popular, if totally made-up (by me), sub-genre of the contemporary

novel of ‘psychological suspense’.

Marie and Nina are

bestest friends and in the last days of a fatal illness, Nina extracts three

promises from Marie which effectively result in Marie taking over Nina’s family

life, whilst at the same time struggling with a desperate yearning to become

pregnant herself despite a disinterested, and unfaithful, partner. So far, so

twisted, and it gets even more twisty, though I have to admit I found it

difficult to summon up much sympathy for Marie. I did learn something, however:

the expression ‘now-wife’ which has a sinister, transitory feel to it.

The narrative voice of

Douglas Lindsay’s Curse of the Clown [Long Midnight Publishing]

is similar to being trapped at a Young Conservative dinner dance with a

hungover Frankie Boyle, for this is a Barney Thomson novel, the ninth in fact,

and Barney hasn’t changed much, he’s still Scotland’s go-to barber for serial

killers.

The plot is insane, the

humour black as night and comes rolling off the page like an incoming flood

tide. Nothing and no one is spared Lindsay’s coruscating wit including

politicians of all stripes (look out for the fake news headlines) from Farage

to Trump to Rees-Mogg, indeed all Tories, and Priti Patel will forever

be ‘the goblin queen’. There are loads of football references and contemporary(?)

cultural ones riffing on the Coen Brothers, Miley Cyrus, Paul Newman in The

Colour of Money, as well as Star Wars and Game of Thrones. There

is also a reference to ‘The Sixteen’ which I am told is a choral group and not

the title of a Tarantino film as I first thought, and a lovely swipe at actor

Robert Carlyle and his chances of ever playing a barber on screen.

But back to the plot: a serial

killer hair stylist is mutilating victims in a particularly grim way, tying sawn-off

appendages to helium balloons because…well, don’t ask. If you’ve ever read a

Barney Thomson book (he’s not a serial killer, he just seems to attract them) you’ll

know what to expect and if you can keep pace with Lindsay’s torrent of spleen,

belly-laughs are assured.

Blood Business

by Barbara Nadel [Headline] is, incredibly, the twenty-second outing in the

award-winning series featuring Inspector Çetin Ikmen, her Istanbul detective,

now retired. But retirement does not lead to a quieter life for Ikmen and an

ensemble cast of policemen, friends, relatives and hangers-on which include his

transsexual cousin, an ageing prostitute, a Kurdish businessman, a dervish, a

Greek Orthodox nun, a Syrian refugee and numerous doctors, lawyers, heroin

addicts and gangsters. All these colourful characters come with dauntingly

difficult names, but fear not, for the book comes with a pronunciation guide to

all 29 letters in the Turkish alphabet (the same number as Welsh; who knew?).

The case dragging Ikmen

out of retirement (it doesn’t take that much doing really) is a gruesome one of

grave -robbing or organ harvesting – or possibly both and the ex-cop uses all

his streetwise skills to ferret out a solution. And what streets Istanbul has;

back streets lined with carpet shops, fish restaurants and wet fish shops, not

to mention cemeteries, their sights and smells wonderfully described by Barbara

Nadel, who also does a pretty good job explaining the melting pot of religions

and cultures in the city where east meets west. (Islam, Christianity and Judaism

I knew, but worshipping a snake goddess called the Sharmeran? You learn

something every day.)

But Barbara Nadel does

not allow her characters to dwell simply in Istanbul’s amazing history, for all

are wary of being implicated, whether they were or not, in the notorious

attempted coup d’etat of 2016. The fear of an authoritarian government

is ever-present, forcing many characters to live their lives in the shadows.

Detective Ikmen is however blessed with the ability to stay out of politics and

political crime: He’d always counted himself fortunate to have dealings only

with killers.

There’s a similar

sentiment expressed by Icelandic police detective Gunna Gisladottir at the

conclusion of Cold Malice [Constable]: I hate it when we get

tangled up in politics. I’d much rather deal with old-fashioned criminals any

day.

Quentin Bates’ latest

novel proves, once again, that he can hold his own with the best practitioners

of police procedurals set anywhere, but especially up near the Arctic Circle,

where the most feared weapon in a cold climate is fire (something I learned

from Alistair MacLean), although Cold Malice starts with an

apparent suicide by hanging and two drownings; one perhaps not accidental and

one which didn’t happen at all in the Indonesian tsunami of 2004.

For those of us, unlike

Quentin (also a noted translator of Icelandic), who only know the country from

the spectacular back-drops to Game of Thrones, there is a sort of

reassuring comfort in learning they have political parties known as the

Moderate Alliance and the Pirate Party, and though politics plays its part,

along with the current debate on climate change, Gunnhildur Gisladottir and her

colleagues have plenty of old-fashioned crimes, both past and present, to

contend with along with the unravelling of several Icelandic family histories.

Cold Malice

is a smooth, solid, professional performance from both its central police

detectives and its author.

I doubt anyone reads Martin

Walker’s pastoral ‘Dordogne Mysteries’ for heart-stopping tension, shocking

violence or hardboiled dialogue. Why would you when there is so much to savour

in the lifestyle of, let alone the crimes solved by, Bruno Courrèges, the chief

of police of the idyllic town of St Denis which lies somewhere between Sarlat

and Perigueux in a stunningly beautiful part of France?

For it is usually St

Denis, with its rugby club, tennis courts, bars, restaurants and markets, that

is the star, although in A Shooting at Chateau Rock [Quercus],

insurance fraud, money laundering and Russian and Ukrainian politics all

disrupt the calm of the Dordogne and force Bruno - eventually – into showing

his colours as an action hero. Before then the reader is treated to much

insider info on French property law, music, sumptuous meals, innumerable

breakfasts, recipes and some very interesting wine recommendations. And

animals. There are lots of animals in this novel: chickens, sheep, horses and

dogs, including a graphic scene where pedigree basset hounds are mated.

The Chateau Rock of the title

gets its local name from being owned by an ageing Scottish bass-player in a

rock band past its sell-by date. There is one scene where the rock star is

urged to throw something out of an upstairs window on to a villain below. In

his prime, the old rocker would have automatically reached for the television

set…

There is no doubt that

Martin Walker has caught the magic of the Dordogne, even if slightly idealised

through a glass of rosé by the British, and along the way imparts some useful

knowledge, not just on matters culinary (invaluable) but also on quirks of French

life such as the fact that Viagra is still only available on doctor’s

prescription and not over the counter as it is here (so I’m told).

Legal

Notice

For legal reasons, Tom

Bradby’s new thriller Double Agent [Bantam] arrived far too late

for inclusion here.

But as I hear good things

about it from both North America and Australia, I am confident that it will be

a book of the month next month.

New

Books (at least to me)

Whilst researching

something else entirely, I came across an(other) author new to me, although one

of his titles did sound awfully familiar.

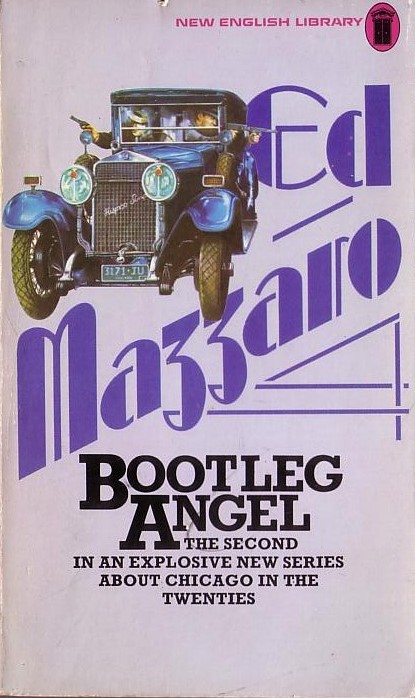

I think, though I am not

sure, that ‘Ed Mazzaro’ was one of several pen-names used by Peter Leslie

(1922-2007) a prolific author who was English, though much of his fiction

output was in long-running American series such as The Executioner and Mack

Bolan books. He was also, over a forty-year career, clearly the go-to writer

for ‘novelisations’ and film and television ‘tie-ins’, among them several Man

From UNCLE stories, Danger Man (aka Secret Agent in the US)

and he was Patrick Macnee’s ghost-writer on novels based on The Avengers.

In the latter stages of

his career, Leslie produced war stories and stand-alone thrillers including, in

1992, The Melbourne Virus, which involves what we would now call

tracking-and-tracing a virus-infected Australian who has arrived in Europe from

the Far East. I must try and hunt the book down to see how it ends.

End

of an Era

After ten years and more

than 100 titles in the Top Notch Thrillers and Ostara Crime

imprints, that small but perfectly formed publisher Ostara has ceased to

produce any new titles, though its backlist of titles will remain available.

As the editor of those

imprints I have taken great pleasure in bringing back some great British

thrillers and crime novels which did not deserve to be forgotten, though they

never were by me.

Among the authors I was

most proud to bring back into print were Geoffrey Household, Alan Williams,

Francis Clifford, Adam Hall, Clive Egleton, Duncan Kyle and James Mitchell, of Callan

fame but also, as James Munro, the creator of hard man John Craig, who in 1964

was touted as a serious rival to James Bond.

Despite the sometimes

tortuous process of tracking down authors, agents and literary estates, it has

been a most pleasurable ten years, not only seeing some old favourites back in

print but also editing new books including the previously uncollected Callan

stories of James Mitchell and the short stories of Pip Youngman Carter (the

husband of Margery Allingham).

One unexpected pleasure

of editing for Ostara was the opportunity to design cover art on occasion and

though it was great fun I know my limitations on that score and vowed not to

give up the day job, if only I could remember what that was.

We’ll

meet again

(from

a safe distance)

The

Ripster

|