|

A Golden Revival

I find it

difficult to believe in the current craze for re-publishing everything ever

written in the so-called ‘Golden Age’, down to and including Agatha Christie’s

notes to the milkman, the works of a true genius are only now being

re-discovered and re-issued.

Camera

Obscuring is

probably the best-known title by Evadne Childe (1890-1965), a ‘Golden Age’

contemporary of Christie, Allingham, Sayers and Marsh, who introduced her

archaeologist sleuth Rex Troughton in 1933 and who made his last appearance in

1963. All her novels were, remarkably, produced by the same publisher, Gilpin

& Co. of London and New York.

Although a

relatively late addition to the cannon, in 1952, Camera Obscuring

was a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic and was filmed in Hollywood,

though the London setting was changed to America, starring Richard Widmark and

Sterling Hayden. It is the first Evadne Childe novel to be re-issued, by

Buckhalter & Byng this month, using the famous cover art of the original

jacket designer known as Flik, and it is astonishing to realise the book –

about a cunningly orchestrated robbery of a mail van – has been out of print

for more than fifty years. Other titles are promised, including Right

Body, Wrong Grave (1937), Dark Moon Over Soho (1945) and The

Robbers Are Coming To Town (1951).

Little is

known about the private life of Evadne Childe, the daughter of an Essex vicar,

who was briefly married to the archaeologist Edmund Walker-Pyne, one of the

first British casualties of WWII in 1939. For many years she was a near

neighbour, in rural Essex, of both Dorothy L. Sayers and Margery Allingham, who

was said to have listed her as ‘Albert Campion’s favourite writer of detective

stories’. [See Books of the Month]

Plague Years

Great

fears of the Sickness here in the City, wrote Samuel Pepys in his diary on 30th

April 1665, but before the Corona virus tightened its grip, a hardened cohort

of crime fiction reviewers met with the publicity team from Headline for

informal drinks, chat and gossip in a famous London hostelry. It turned out to

be one of the last events on the crime fiction social calendar before the

quarantine descended.

Without

recourse to speeches, PowerPoint presentations or author readings (or even

authors), the enthusiastic publicists enthused the gathered hacks about their

forthcoming crime titles from contemporary psychological/domestic suspense such

as Karen Hamilton’s The Last Wife (in June), to the traditional

‘village mystery’ of Ann Granger’s A Matter of Murder (July) to exotic

locations such as Barbara Nadel back on an Istanbul beat with Blood

Business (in May), to the latest WWII thriller by Simon Scarrow Blackout

(August) and established bestseller Martina Coles’ Loyalty in

October.

And one

unfamiliar name which I am now looking forward to very much: S.A. Cosby. I have

no idea of Mr Cosby’s first names but his novel Blacktop Wasteland,

which is published in August, comes with terrific advance notices from Lee

Child, Dennis Lehane, Walter Mosley and Steve Cavanagh, so I for one intend to

take it seriously.

Another

new American name to watch out for is Stephen Spotswood, whose Fortune

Favours The Dead is published under Headline’s Wildfire imprint in

October. Set in New York in 1946 and starring a female private eye duo, this is

said to be a take on a ‘Golden Age’ locked-room mystery but owing more to

Chandler than Christie.

For legal

reasons I would not have attended the inaugural Lyme Crime festival which was

scheduled to take place in June in that fine coastal resort of Lyme Regis, one

of my favourite seaside destinations which is also home to one of my favourite

second-hand bookshops.

I wished

it every success, especially as I only found out about it just as the news

reached me that crime fiction conventions in Bristol (Crimefest),

Belfast (Noireland), in Maryland (Malice Domestic), Chicago (Murder

& Mayhem), in Florida (Sleuthfest) and San Diego (Left Coast

Crime) have all been postponed due to fears of spreading the Corona virus.

It is

also sad to report that the Dorothy L. Sayers annual lecture at Witham in

Essex, this year to be given by no less than Professor Barry Forshaw has been cancelled.

Barry’s lecture was to have been something like the 23rd or 24th

in the series; the inaugural lecture being given by P.D. James, the second by

me and the third by Minette Walters. Another event regularly in my diary is the

annual birthday lunch for Margery Allingham, held in May by the Margery

Allingham Society. I was particularly looking forward to this year’s party as

the guest speaker was to have been that erudite cosmopolitan Mr Peter

Guttridge, and I was so looking forward to introducing him.

I have to

admit that I have personally succumbed to the craze for panic buying created by

the plague scare and have shamelessly stock-piled large quantities of Sicilian

Vermentino and as much Amarone as I could find. Suddenly self-isolation,

considering all the books I have to read, doesn’t seem too bad.

Memory Lane

I was

recently asked how long I had been ‘doing that bloody column’ by which I

presume they meant Getting Away With Murder. Always being one to help the

police students of the genre in their researches, I delved into the

archives and discovered that it must be twenty years or more since this column

first appeared in the pages of the late, lamented Sherlock magazine. GAWM,

as it affectionately came to be known (‘GAWM-less’ in Yorkshire) moved to the

newly electronic version of Shots magazine in 2006 and appeared

sporadically until 2010 when, for reasons which totally escape me now, it was

decided to go monthly.

Looking

back to that first column of the New Era of eZines rather than magazines

(though the column survived until this month in print form, syndicated in the

American magazine Deadly Pleasures), I was surprised to find that even

back then I was having reservations about certain aspects of the work of a well-known

author: James Lee Burke.

Am I the only

long-time fan (over 18 years now) who is finding (Dave) Robicheaux’s

sanctimonious and arrogant approach starting to grate? Is it his insistence

that crime is usually a result of genetic defects or alcohol addiction, his

lip-service Catholicism, or his bullying tactics which would by now have got

him dismissed from the police force, even in Louisiana (or at least his ass

would have been sued off)? In his latest outing, he over-reacts so hugely to a

man he suspects of trying to poison his pet three-legged raccoon (sad or what?)

that you begin to fear that someone so unstable should be walking around with a

badge and a gun. Especially the gun.

Is Dave

Robicheaux becoming the Grumpy Old Man of crime fiction? Or is it me?

It was also rather spooky to discover that in that column, back in 2006,

I featured another American, Walter Satterthwait, who featured briefly in last

month’s column following his untimely death at the age of 73.

From his name

alone, you might think Walter Satterthwait was a bluff, nineteenth-century

northern brewer. In fact, he’s American and one of those rare breed of

Americans who (a) have a passport and (b) have used it, as he has lived in

Africa, Greece and the UK, as well as Santa Fe and, currently, Los Angeles. He

is known for two distinct types of crime novels. His excellent private eye

books featuring Santa Fe based Joshua Croft, and then his tongue-in-cheek

period mysteries, most famously Miss Lizzie

(starring Lizzie ‘The Axe’ Borden), the quite brilliant Wilde West

(starring Oscar Wilde and a very suspect Doc Holliday) and the 1920s series

featuring Pinkerton agent Ned Beaumont with a supporting cast ranging from

Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle to Ernest Hemingway and a young Adolf

Hitler.

Now he adds a

third-string to his bow, with the serial-killer thriller Perfection,

just out in the US from Thomas Dunne Books (St Martin’s Press). Walter being

Walter, he can’t resist stirring it and he has a serial killer who only preys

on “ladies of size” which probably hasn’t gone down too well in some parts of

the US.

Although

championed by editor Elizabeth Walter at Collins Crime Club in the late ‘80s

and early ‘90s, Satterthwait has been disgracefully blindsided by UK publishers

for about ten years now, although he is incredibly popular in Germany. (Well,

up to the Hitler book, anyway.)

Early in his

writing career he even had a biography written by an ardent fan, Sleight

Of Hand, published in a limited edition by the University

of New Mexico Press in 1993. My copy carries the dedication “This is bound

to become extremely valuable. Very few copies were printed, fewer were

distributed, and none were sold.” Which sort of shows that the experience

didn’t go to his head.

Walter’s sad, though not unexpected, death has provoked a host of

tributes and memories including one which recalls the story of how he awarded

himself the title International Lunch Whore. The ‘International’ bit came from

his frequent trips to Europe to meet his European publishers, not as here,

where he was ‘off duty’ in London with his then wife Caroline, being shown the

important tourist sights (the inside of a tavern) by Sarah Caudwell and myself.

On one

European tour he famously diverted to Paris for a free lunch with his French

publisher and then took a train to Milan for a free lunch with his Italian

publisher. He later admitted that travel and hotels costs for that diversion

had been $1,275, but as he said philosophically, “when it comes to free

lunches, money is no object”.

Film Fun

I was

distracted, nay furious, to hear a rumour that Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 western The

Wild Bunch was being re-made by Mel Gibson. Why? Wasn’t the remake of The

Magnificent Seven travesty enough?

Whilst

trying to research this awful news, I came across several other titbits of

filmic fun. Something called Netflix has produced Spenser Confidential,

which I am told is “loosely based” on the books of Robert B. Parker and

latterly Ace Atkins, featuring the highly-regarded Boston private eye. From

what I have seen, “loosely” is certainly the word. (Ed: See what Mark Timlin thinks of it.)

I am more

hopeful about the filming of Jim Thompson’s 1964 gritty thriller Pop.1280

with its famously cynical opening monologue by a small town sheriff who ‘has it

made’ basically by doing as little as possible to fight crime.

Anything

by Jim Thompson, a master of American noir, is worth reading and film

adaptations rarely less than interesting. I have, shamefully, never seen the 1981

French film Coup de Torchon, which was based on Pop.1280,

but I have heard very good things about it.

Also

rumoured to be in the pipeline is In the Garden of The Beasts,

set in pre-war Nazi Germany and starring Tom Hanks, a high-profile victim of

the Corona virus. This turns out to be based on the book by Erik Larson and

not, as I first thought, the 2004 thriller by Jeffery Deaver with a similar

title.

Another

reason for my confusion was that I remembered the late Philip Kerr once telling

me over lunch of Tom Hanks’ interest in the period and his Bernie Gunther books

in particular, and there was speculation about a possible television

adaptation. What became of that suggestion I do not know, but I am aware that

Philip, in a review for the Washington Post in 2011, really rated Erik

Larson’s work of popular history, as apparently did Tom Hanks, saying that it

read like ‘an elegant thriller’. If it impressed Philip, then I will find a

copy (I already have) and read it almost immediately.

Best Served Cold

I was

reading up on Jacobean ‘revenge tragedies’ (as you do) recently and came across

an interesting introductory essay by the late Professor Gamini Salgado which

discusses the pitfalls of putting dramatists and their plays into particular

genres or sub-genres such as ‘the Revenge Play’. Professor Salgado, although

Sri Lankan by birth, displays the manners of a perfect Englishman when he

wrote, in 1965:

Literary

categories are always arbitrary and creative artists have always shown a

healthy disrespect for them (if, indeed, they have been aware of their

existence). Everyone knows that there is a class of fiction called the

thriller; it is perhaps the most popular form of fiction in our day. It has certain

broad characteristics, detection, mystery, suspense, and so on, and its

practitioners range from Mr Mickey Spillane to Mr Graham Greene.

The

Professor made a good point, though I just wondered how often Mr Spillane has

been referenced in a book which deals in the main with fellow thriller writers

such as Shakespeare, Marlowe, Kyd, Webster and Middleton.

Famous Names

Late last

year I was contacted by an American reader, one with impeccable taste in

hardboiled crime fiction, asking if I had read Neil Clark’s biography of Edgar

Wallace, Stranger Than Fiction, saying that he understood no-one

read Wallace any more in England and added (very worryingly) ‘like John D.

Macdonald here in the US.’

I do hope

he is wrong about John D. Macdonald, though I can understand why Wallace has

fallen from memory, despite having an impressive London pub named after him and

being often touted as ‘the man who created King Kong’ – although

devotees of the original movie have long argued about his contribution.

There is

no doubt, though, that Wallace (1875-1933) was a huge influence on the crime

and thriller fiction scene, writing around 170 books and accumulating worldwide

sales of an estimated 200 million copies, starting with his legendary debut The

Four Just Men. He was also, for many years, the king of the horse racing

thriller decades before Dick Francis made that sub-genre his own, and much more

heavily involved than I realised in the world of the theatre.

I wish I

could say that Stranger Than Fiction made me rush to read an

Edgar Wallace novel or two (or twenty) but I’m afraid it did not. There is

surprisingly little analysis of Wallace’s thrillers (and their popularity) as

the book concentrates more on his early life as a journalist and his

involvement in the theatre and there are constant, and I do mean constant,

references to how profligate he was with his money but how ‘generous he was to

others’ (the milkman he owed £70 to in 1905 might disagree). But I would

caution any potential reader not to skip the first half of the book otherwise

they will miss the chapter where it is explained that Edgar and his second wife

Violet decided on the pet-names of Richard and Jim for each other. Without this

forewarning, the second half of the book could strike the unwary as slightly

odd as Edgar, having divorced his wife Ivy in 1919, is suddenly in partnership

with a Jim.

I am not

sure what Dorothy L. Sayers thought of the work of Edgar Wallace; probably not

very much. Her main stint as a reviewer of crime fiction came after Wallace’s

death, but as a writer, she would have been establishing her career in the

1920s when Wallace was at the peak of his popularity.

|

|

Catalogue of Crime

I am indebted to the very impressive catalogue of forthcoming books for the second half of the year from publisher Head of Zeus for reminding me of two crime writers I realised I had not read for, disgracefully, almost a decade.

I met the charming Brian Freeman in London when he was first published in the UK and rated highly his thrillers set in chilly Minnesota starting with Immoral in 2005. Now he has, I suspect, fulfilled a teenage fantasy (as an admitted fan of the originals) by taking on Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne franchise with The Bourne Evolution which is scheduled for publication in July.

Sebastian Fitzek made headlines across Europe in 2006 when his debut psychological thriller Therapy knocked The Da Vinci Code off the top of the bestseller list in Germany. It did very well when published here in the UK in 2008 and I was surprised it was not a contender for the Crime Writers’ Association’s International Dagger, but I was determined to keep an eye out for his future titles. Of course I failed miserably in my vow to do so, but am delighted to see that Head of Zeus are to publish The Package in August along with Passenger 23 in November, neither of which, I believe, have appeared in English before, although both were highly successful in Europe.

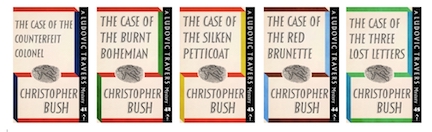

Enough Bush To See You Through

Those enterprising chaps and chapesses at Dean Street Press are making sure that fans of the detective stories of Christopher Bush (1885-1973) will have plenty to read in the coming months of self-isolation, by republishing, next month, a further ten titlesto join the 40 Bush titles they have already revived. In terms of the adventures of Bush’s series detective Ludovic Travers, these represent books 41-50.

The new titles are The Cases of (respectively): The Counterfeit Colonel, The Burnt Bohemian, The Silken Petticoat, The Red Brunette, The Three Lost Letters, The Benevolent Bookie, The Amateur Actor, The Extra Man, The Flowery Corpse and The Russian Cross. Detection Club member Christopher Bush’s speciality was the ‘Unbreakable Alibi’, and his work drew praise from countless contemporaries for his tight plotting, urbane style and imaginatively varied mysteries. Dedicated fans not surfeited on those existing 50 titles will be eagerly anticipating the remaining 14 still to be republished.

Books of the Month

Though I

did recommend it earlier in the year, the late Philip Kerr’s 2005 thriller Hitler’s

Peace, now at last published here (Quercus) will be for many readers

their automatic book of the month, if not their year.

I hope

people will read it not just to remind them of what a story-telling talent we

have lost, but because it is actually a fast-paced and audaciously speculative

historical thriller and the Quercus edition comes with a heartfelt afterward by Howard Jacobson, who spoke so eloquently about Philip at the launch of his posthumous novel Metropolis.

I am not

at all surprised that Chris Whitaker is widely regarded as one of crime

fiction’s rising stars, but I am astonished to discover he is British, so

convincing is the small town American setting of We Begin At The End,

out now from Zaffre.

At times

it reminded me of To Kill A Mockingbird, but that probably has more to

do with the fact that a character surname is Radley (and my specialist subject

on Pointless might just be the early films of Robert Duvall), and my

overwhelming impression was that this was a first rate American crime

novel. Its focus is a pair of siblings, the central character being a

13-year-old girl who becomes the mother and protector of her younger brother

after a series of very unfortunate events indeed. This book is so American, the

reader firmly believes that the best way to cure a thirteen-year-old girl

suffering severe emotional trauma is, of course, to teach her to shoot a

handgun.

We

Begin At The End has a convoluted plot covering guilt and innocence, small

town mores, dysfunctional families and an outrageous property scam and is, in

the main, thoroughly convincing. There are just one or two places, deep into

the book, where the young protagonist, who has led a sheltered life both

socially and educationally, comes out with opinions which seem far too advanced

for her age. Still, there is much here to engross the crime fiction fan and, in

the skill of the writing, an awful lot to admire.

For a

totally exhilarating romp through Ancient Rome, Lindsey Davis’ latest Flavia

Alba novel won’t be beaten and offers an immersive experience of a vibrant

world full of real, recognisable characters.

The

Grove of the Caesars, out this month from Hodder, sees our intrepid female

investigator Flavia Alba venturing across the Tiber to the

gardens bequeathed by Julius Caesar to the people of Rome, later to be taken

over by the Emperor Augustus (because ‘he interfered in everything’) and now,

some 140-odd years after Julius’ all-got-it-infamy moment, the site of a

discovery of some ancient scrolls seemingly containing ‘lost’ philosophical

writings. Are the scrolls fakes? Is even their supposed author a fake? (Who

would think of creating a fake author, even on April 1st?)

The joy

of The Grove of the Caesars, as with all Lindsey’s Roman novels,

comes not so much in the plotting nor even in the fine detail of life in Rome

in the second half of the first century, but in the way her characters

deal with that life. They are treated to respectable music (‘everyone keeps

their clothes on and listens’), they have to sit through a display of proper

Greek dancing (‘the utterly boring kind’), they debate whether The Stargazer is

‘the lousiest bar on the Aventine’ when in fact everyone knows The Winged Pig

is (its food started an epidemic), and there is a priceless exchange when the

unearthed scrolls are dismissed as ‘garbage’: Who writes garbage – Most

authors; But who reads garbage? – The bloody public!

Lovely

stuff, worth every denarii.

For a

very impressive slice of rural American crime-writing, I can highly recommend The Bramble and the Rose by Tom Bouman, from Faber. Set in the small town

(and big woods) of the wonderfully-named Wild Thyme in Pennsylvania, local cop

Henry Farrell is called upon to investigate a headless body found in the woods.

There are clear and dangerous signs that a bear attack was the cause and,

indeed, a bear, for whom the story does not end happily, is involved. Yet as

the identity of the victim emerges, the plot extends into a criminal conspiracy

which eventually encompasses Farrell’s friends and extended family.

Henry

Farrell is a flawed hero, at times cold and distant when it comes to personal

relations and alternately irrational with anger when his young nephew is

threatened. This being the American ‘wild’ there are lots of details about

tracking and camping out and also about guns, which are often referred to just

by the calibre of bullets they take, but this is a very finely written book,

often quite elegiac and for all his faults, Farrell is a worthy hero and one

worth keeping an eye on.

Now read this

very carefully for I will type it only once. The title of Malcolm Pryce’s new

novel is The Corpse in the Garden of Perfect Brightness (out now

from Bloomsbury), which vies in length with his The Unbearable Lightness

of Being in Aberystwyth, a fine example of his earlier work in the

field of surreal and hysterically funny Welsh noir – a field he distinctly made

his own.

In Corpse… Pryce’s

humour turns from Wales and all things Welsh, on to steam train buffs (with

some fondness) and the British Empire (with less affection), with lots of movie

references along the way, particularly King Kong. It is a gentle fantasy

adventure in which railway detective Jack Wenlock travels east of Suez to trace

the mother he never knew. As the year is 1948 and the Great Western Railway has

been nationalised into British Rail, a railway detective has probably got time

on his hands, even if he is pursued by a criminal international organisation

(but that’s another story).

Surprisingly,

or perhaps not, Pryce found more satirical targets among the Welsh rather the

in the far flung Empire, although there is one wonderful story about the

Japanese attack on Singapore in 1942 and the positioning of British artillery

on the edge of a golf course, which I totally believe. There’s also a starring

role for a giant squid, the great white whale to a Captain Ahab figure known as

Squideye, which adds to the craziness – and there is a lot of crazy in the

book.

But then,

whenever the setting is Thailand and there are railways and engines going chuff

chuff I always automatically think: ‘Madness…madness…’

Devotees

of spy fiction looking for something new, even if the synopsis of five spies,

one of them a traitor sounds a tad like Tinker Tailor, should look no

further than The Message by Mai Jia (Head of Zeus), who may be

China’s John Le Carré.

Mai Jia’s

latest novel (he is a huge bestseller in China) is set in 1941 when the country’s

defence against Japanese aggression was split between the Nationalist forces of

Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist Party of Mao Zedong. In Hangzhou, the

Japanese puppet government isolates five code-breakers, two of them women, not

to combat the activities of the resistance armies, but to discover which one of

them has been passing information to the communists.

The

result is a fascinating play on history, loyalty, logic and coded puzzles and

the setting, and point of view, will certainly be unusual to European readers.

For those not familiar with the history of the period, there are copious notes

and explanations within the text, which in other contexts could slow or distort

the narrative, but here are invaluable.

Not new,

in fact the book was first published in 1977 and my paperback edition is now exactly

thirty years old, but Laidlaw by William McIlvanney is a book of

the month every month. Especially so this month as a new edition appears from those

classy publishers Canongate.

If you’ve

heard the expression ‘Tartan Noir’ and wondered what it meant, this is where it

all started. A stone classic.

Can one

possibly say anything new about Lynda La Plante, the creator of Widows and

the iconic Jane Tennyson in Prime Suspect?

Of course

one can, for this month she launches new, contemporary crime series with a new

leading character, Met detective DC Jack Warr, in her new novel Buried,

from Zaffre. Jack Warr’s first case begins with a fire in a derelict cottage –

and if you’ve ever heard the expression ‘long pig’ and wondered what it meant;

all is explained. It seems a rough introduction for Jack Warr, recently arrived

in the big city from Devon (where he supports Plymouth Argyle, though that

shouldn’t be held against him) with his partner. Will he survive the drastic

change from rural to urban policing? You bet he will. Will we see him on a

screen somewhere soon? Don’t bet against it. This author has form in such

matters.

It was

the French medievalist Jean Gimpel who pointed out (at least to me) that the

Viking invasions of the early eleventh century were the last invasions suffered

by Western Europe. From then on, it was Western Europe which did the invading,

across the world, with varying degrees of success.

Gimpel,

of course, could not have foreseen the invasion of Scandinavian crime fiction in

the twenty-first century and few (pace Professor Forshaw) thought it

would last as long as it has, or throw up as many firm favourites, such as

Camilla Lackberg, who is said to be the sixth most-read author in Europe now,

as well as a runner-up in Sweden’s Strictly Come Dancing.

The

Gilded Cage, published this month by HarperCollins, has already been a

#1 bestseller in all Scandinavian countries and high in the charts in Germany,

France, Italy, Portugal and probably all the countries where it has been published:

a successful invasion indeed. Several years ago, an ambitious young journalist named

Boris Johnson wrote a very good article attempting to explain the appeal of

Scandi-crime. I remember keeping a copy and must try and dig it out.

And just

when this old and embittered hack thought there could be nothing new coming out

of the frozen northlands, I discover the adventures of Hella Mauzer, a splendid

creation by Finnish author Katja Ivar. Deep As Death, from Bitter

Lemon Press, really is very, very good. The setting is Finland in 1953, a cold

winter during a Cold War, and call-girls are ending up in Helsinki (‘a city for

walking fast’) harbour. It ends up as a case for Hella Mauzer, a former cop

turned private eye whose struggles against patronising, institutional sexism

form a vital plot strand.

Mauzer is

an engaging protagonist, the 1950’s setting and characters totally convincing

and Katja Ivar, I think, writes in English and does so wonderfully.

I cannot

resist mentioning Mr Campion’s Séance, published at the end of

this month by Severn House, for it illustrates a point I made earlier about

Margery Allingham’s legendary hero Albert Campion and the Golden Age author

Evadne Childe.

The

connection between the two could not be more clear as the plot of Mr

Campion’s Séance revolves around the detective stories of Evadne

Childe, from 1946 to 1962, which seem to be able to predict, or provide

blueprints, for real crimes. Set primarily in seedy post-war London, the whacky

world of publishing and the far more respectable world of psychics and mediums,

Allingham afficionados will appreciate the appearance of three of Margery’s

favourite policemen – Oates, Yeo and Luke. Well, I hope they do.

Corona Latest

Some optimism still exists in our virus-ridden world. Regular readers of this column in Italy report that although the medical situation there is serious, they have not fallen foul of the draconian policies of well-known supermarkets to limit customers to three examples of every item purchased, which I am sure was never intended to apply to wine. In Italy, I am assured that wine, and indeed whisky, are in plentiful supply.

And in Cambridgeshire, I hear of a pub which, faced with closure to encourage ‘self-isolation’, is selling off its stock of cask-conditioned ale at £1 a pint. Naturally, I have no intention of telling you where the George & Dragon is.

Stay safe,

Stay Home,

Stay Away from Me,

The Ripster.

|