|

Reviewing the Reviewers

News of the death of Marcel Berlins, the long-serving crime fiction critic for The Times, came too late for last month’s column but my appreciation of Marcel can be seen[here]and prompted a flood of emails registering shock and sadness that the genre had lost such a marvellous champion. His funeral took place in Paris, but a memorial will be held in London in October.

Of all the comments received, I take a personal pride in one in particular, from an established thriller writer: You introduced him to me at a Hodder bash. I remember the two of you brought a glow to the room, a very welcome levity and conviviality.

I will miss him as a fellow critic, a supportive reviewer and, above all, a friend and his passing made me reflect on how lucky I have been to have known, let alone be reviewed by, some real connoisseurs of the genre: H.R.F. (Harry) Keating, Philip Oakes, Matthew Coady, Tim Binyon, Bill Pardoe, Val McDermid, Philip Kerr, Maxim Jakubowski, Anthony Lejeune, Julian Symons, Peter Guttridge, Jake Kerridge and even the much-maligned (at least in this column) Barry Forshaw. All good people, all excellent company, especially when talking about crime fiction.

The Letters’ Page (if we could afford one)

Apart from the outpouring of sadness over the death of Marcel Berlins, it was a bumper month for letters to this column, amazingly few accompanied by legal writs and threats as is usual.

The Irish king of noir Ken Bruen informs me that he finds it Terrific to see the covers of your books on the page. Well, thank you for that Ken, I must remember to feature them more often. Much more interesting is a missive from reader David Salter who picked up on my item linking the Quiller character created by Adam Hall with the more recent Jason Bourne in the films from the books of Robert Ludlum.

David points out that in the Quiller novels, when he is being prepared for a mission he is often asked about his final wishes, should he fail to return. This always consists of only one thing - either a single, or a dozen or sometimes a room full of red roses for Moira. Moira is the always off-stage girl friend of Quiller, who lives in Paris and is, apparently, a film-actress.

In The Bourne Betrayal, a Jason Bourne ‘continuation’ by Eric van Lustbader published in 2007, a friend of Bourne’s is fatally wounded and his last wish is when this is all over I want you to send a dozen red roses to Moira. You'll find her address in my cell phone.

The Moira connection is not accidental as Van Lustbader dedicates the book: "In memory of Adam Hall (Elleston Trevor), a literary mentor. The roses are for you too.".

Legends at Lunchtime

In his annual whistle-stop visit to London, Canadian book collector and reviewer Steele Curry hosted another of his intimate lunches for thriller writers he admires – and me.

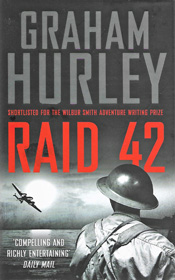

The guests of honour this year were veteran television reporter and thriller writer Tim Sebastian and veteran crime writer Graham Hurley, both of whom have new novels out this year – Fatal Ally and Raid 42 respectively – which come highly recommended by this column.

Triple Whammy

For legal reasons I was unable to attend the launch party for The Long Call by Ann Cleeves, out this month from Macmillan.

I had hoped to congratulate Ann not just on having a new book out but on the news that the television rights to The Long Call– the first of a new series set in Devon – have been snapped up by the producers of Vera and Shetland, both spectacularly successful drama series based on Ann’s books.

Hornblowing

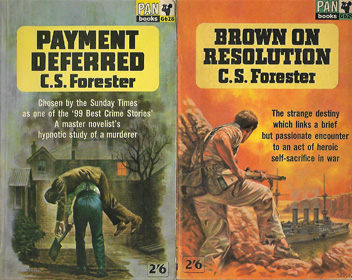

C.S. Forester will always be linked to his historical ‘Hornblower’ books set in the British navy during the Napoleonic wars, but as a prolific writer over several decades, he covered a number of popular genres producing ground-breaking crime novels such as Payment Deferred in 1926 and a stunning World War I thriller, Brown on Resolution in 1929.

During, and immediately after World War II, he produced novels and short stories based on wartime themes and events, including a notable exercise in ‘what if’ history in the story If Hitler Had Invaded England which can be found in the collection Gold From Crete.

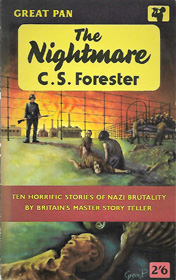

I have recently discovered another Forester collection, The Nightmare, first published in 1954 and clearly inspired (if that’s the right word) by the post-war Nuremberg Trials. Described by one reviewer as ‘vignettes of villainy written by a master storyteller’, the stories are in the main, fictional versions of real examples of Nazi brutality plucked from legal documentation and given a human, or more often inhuman, face. It’s publication coincided with that of the more famous, not to say notorious, bestseller Scourge of the Swastika by Lord Russell of Liverpool.

Forester fictionalises real events: the fake attack on Germany by ‘Polish’ troops (actually concentration camp prisoners) in 1939, the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ and its legacy of ruthless betrayal, life and death in the camps and the July Bomb Plot, but serves up a final story as pure fiction. In The Wandering Gentile, a man driving from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 1954, stops to pick up an odd pair of hitch-hikers; an elderly married couple in a somewhat dishevelled state. The husband seems particularly confused, thinks he is going to Washington and speaks only German. When the old man refers to his wife as Eva and the car-driver’s dog as Blondi, there are no prizes for guessing who the passengers are. But is anybody going to believe that?

Spanish Practices

Last month I mentioned The Most Difficult Thing, the new novel by Charlotte Philby, granddaughter of the infamous double agent Kim, who in his career as an MI6 officer and KGB mole has appeared as a character in many spy novels starting with (I think) Gentleman Traitor by Alan Williams in 1974.

Never being one to pass up an easy segue, I should have mentioned that Kim Philby makes a wonderfully unsettling cameo appearance in Graham Hurley’s excellent Raid 42 (Head of Zeus), deliberately spooking (see what I did there?) an MI5 agent who is encroaching on ‘his’ turf – Philby at the time, during WWII, being head of the Iberian section of MI6. I now learn, from a colleague in South America, that Philby also appeared El Aguila y El Wolfram, a Spanish thriller set during WWII, by Miguel Angel Pereira Casas, published in Madrid in 2012. I can say no more about it as my knowledge of modern languages usually extends no further than the wine list.

The real Philby and his legacy of treason, also features crucially in Andrew Williams’ new novel Witchfinder – see ‘Books of the Month’.

My cross-head, ‘Spanish Practices’, will be a familiar phrase to Fleet Street hacks of a certain (advanced) age and is, I think, appropriate as Kim Philby had a cover career as a journalist.

Writer on Writer Action

Nevil Shute (1899-1960) was a very successful popular novelist in his day, but is rarely thought of in terms of crime-writing or thrillers, though many of his books did contain crimes and were certainly thrilling. He is perhaps best remembered for A Town Like Alice and On the Beach, both of which made notable films.

During WWII he published numerous morale-boosting novels including the gentle, romantic, Pastoral in 1944 about a love affair between an RAF bomber pilot and a WAAF officer. It is also a hymn to the English countryside in a this-is-what-we’re-fighting-for sort of way, and a fascinating insight into the mores and social conventions of the period.

Although Shute was as far from Peter Cheyney in style and story-telling as it was possible to be, Cheyney’s immensely popular thick-eared faux American crime stories get a memorable name-check in Pastoral.

In a scene in the RAF base mess, our hero, a decent, rather innocent type, is trying to interest a fellow officer in a monster pike he has caught whilst out fishing, but: Davy was reading about Lemmy Caution and his gorgeous dames, and clearly has other things on his mind: The dame had brunette chestnut hair that fell down on a bare shoulder, and slim bare ankles thrust into white mules, and grey eyes, and curves in all the right places, a small black automatic pistol that pointed straight at Mr Caution’s heart. It was asking too much to leave that for a dead fish.

The interesting thing is that Nevil Shute did not think it necessary to mention Peter Cheyney (1896-1951) by name, as everyone in 1944 would know who Lemmy Caution, his most famous fictional creation, was. I have no idea which Cheyney novel Shute was parodying – it could have been any of them - but it might have been his 1936 debut This Man Is Dangerous.

Billion Copy Dame

There is a new reissue of Agatha Christie’s 1941 novel Evil Under The Sun out from HarperCollins. The accompanying press release claims that this is Christie’s ‘most famous novel’, which I would dispute most strongly, and that two billion copies of her books have now been sold worldwide, which I did not know, but would certainly not dispute.

The new paperback comes, it says here, ‘with a stunning new cover’. Be that as it may, and call me retro if you must, but I have a soft spot for my battered 1964 version which still holds seawater stains and granules of sand from a visit to Burgh Island, which is (occasionally) off the Devon coast.

Me Neither…

I am genuinely in awe, as I have some experience in the field, of the Dean Street Press’ enthusiasm for reissuing ‘forgotten’ books from the so-called ‘Golden Age’ even if many of the authors they are reviving elicit the response “No, me neither” when I cite their names. In my defence, I am not entirely ignorant of their backlist; I was well-aware of Patricia Wentworth (one of whose detective stories inspired Colin Dexter to start writing on the grounds that he could do better) and I actually knew Tim Heald.

And indeed I was aware of Christopher Bush (1885-1973) and was certainly impressed by Dean Street’s ambition to reissue all 62 of his novels, but before a regular reader can have worked their way through half of those, Dean Street keeps up the pressure this October by reissuing the first 10 (of 54) novels by Brian Flynn (1885-1958), and once again, the plaintive cry goes up: No, me neither.

I don’t know if either Bush or Flynn would have qualified as being what Julian Symons called ‘the big producers’. Neither wrote as many novels as Agatha Christie and nowhere near as many as John Creasey (whom Symons had in mind) and neither stayed in print very long, unlike Agatha, but not Creasey.

Yet there can be no doubt that many ‘Golden Age’ authors were frightfully prolific and those who can manage to produce 50+ titles in a writing career, without repetition, deviation or disappointment, are notably thin on the ground these days.

Thus I was surprised to discover an author, Joy Ellis, and a publisher I had never heard of, Joffe Books, who appeared to be on the way to qualifying as a contemporary ‘big producer’.

Best known, though I am ashamed to say not by me, for a series of books set in the Fens of East Anglia, Joy Ellis can boast, according to the Joffe website, ‘over 1.5 million books sold’, an achievement she is to be congratulated on, along with the responsibility for buying the first round should we ever meet.

What struck me as really impressive though was that according to that invaluable resource, the Fantastic Fiction website, Joy Ellis appears to have written and published thirteen novels in the last three years. Surely, as they say, some mistake? Of course there was, and I had made it. I had not realised that Joffe Books were publishing new editions of Joy Ellis’ backlist. Once I had, I breathed a sigh of relief, for if the current norm is to write 13 crime novels in three years (that’s one every 2.7 months) then I realise I am in the wrong line of work.

|

|

Books of the Month

The historical crime novel, or ‘history mystery’, is a noble and established sub-set of the genre, as is the historical spy story (just think of Alan Furst, John Lawton, Joseph Kanon or Robert Littell), as is the spy story which incorporates real figures from world events, such as prime ministers, presidents, despots and assorted military supremoes. Some even include real spies as characters. In his new novel, Andrew Williams, who once cheekily had a wartime Ian Fleming as a character, has produced not so much historical fiction, as a fictionalised history of the British spying establishment of the early 1960s.

Witchfinder, out this month from Hodder, is an epic of the deceit and distrust which riddled British Intelligence in the wake of the defection of Kim Philby to Moscow in 1963 and the frantic need to unravel the ‘Cambridge ring’ of spies. Was there a Fifth Man? Who recruited them? Was there an equivalent ‘Oxford ring’? Who tipped off Philby? MI6 suspects MI5 but everyone knows MI6 is probably to blame. Or is it?

It was a turbulent time in the spy world. In Britain, spy scandals were making the headlines almost every week, with foreign agents or traitors being uncovered, imprisoned or swapped. The British were perceived as completely untrustworthy by their American allies and – Good Lord! – one British spy had come in from the cold and started writing spy fiction.

Andrew Williams populates his novel with a minimum of fictional characters, the main one being the narrator Harry Vaughan, a Welshman (and he never lets you forget that) who is recalled from his Vienna posting to join a working party investigating where the espionage establishment is most leaky. He encounters, among others, Sir Dick White, Maurice Oldfield, Sir Roger Hollis, Sir Anthony Blunt, Sir Isiah Berlin, Goronwy Rees, Tom Driberg MP and has to work with Peter Wright who went on to write his infamous Spycatcher memoir twenty years later. All in all, a veritable Who’s Who of spookery.

The amount of research which has gone in to Witchfinder is simply staggering and Williams handles his material well, wonderfully pulling off the trick that the reader believes the narrator was there and did that – especially in the interviews with the aristocratic traitor Anthony Blunt. Although many component parts of this sorry saga are both well-known and have featured in spy fiction over the years, this is a splendid one-volume fictional history of a period of espionage where truth really was dafter than fiction.

In the 1960s, with the security services locked in internecine warfare, mistrusted by its allies and spies and traitors popping up everywhere, spy fiction boomed. Just as our real spies were perceived as pretty useless, fictional ones such as Quiller, Jonas Wilde, Jason Love, Charles Hood and Philip McAlpine were there to save the day. Not to mention a certain Mr James Bond, proving that fiction is more comforting than fact.

One of my favourite bad taste descriptions of all time was when Gore Vidal wickedly described a character looking at something with all the astonishment ‘of a Donner Party survivor confronted with an all-you-can-eat buffet’.

For anyone baffled by the reference, the Donner Party was a wagon train of pioneers trekking to California in 1846-47 which got itself stranded and snowbound in the Sierra Nevada mountains. The result was starvation, murder and cannibalism, much of it centred on a ‘Lost Camp’. As if the real events of that winter were not horrific enough, those American masters of the gothic thriller, Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, pile on the horror and mystery in Old Bones from Head of Zeus, which launches a new series for them, featuring Nora Kelly, a curator at the Santa Fe Institute of Archaeology, in search of that ‘Lost Camp’. This is history and archaeology red in tooth and claw. Anyone expecting a relaxing episode of Time Team should check their pace-makers before opening this one.

I would never dream of questioning Felix Francis’ knowledge of horse racing, for he is a thoroughbred in that field, although in his new novel, Guilty Not Guilty, published this month by Simon & Schuster, much of the action takes place in police cells or interview rooms, a coroner’s court, a hospital and a crown court rather than on a race course. There is one scene, though, where during an attempted murder, a small car is propelled over rather than through a hedge with the speed, if not the grace, of a horse clearing The Chair during the Grand National.

However, I have to be picky when it comes to Felix’s film knowledge. The hero of Guilty Not Guilty (the title is clever, not a misprint) is the third son of an earl and at one point (when suspected of murdering his wife) he references the classic film Kind Hearts and Coronets, which happens to be one of my favourites. Our hero, when aged twelve, had ‘obsessed over that film, watching Alec Guinness…[and] daydreaming about cunning ways I could emulate him and elevate myself up the family pecking order.’ Now Felix admits his hero was very young when he saw the film and I suspect his current copy-editor is too young to remember it, but it wasn’t Alec Guinness who played the mass-murdering social climber, it was Dennis Price. Alec Guinness played all his victims. But I doubt such carping will prevent Guilty Not Guilty from being one of this month’s best sellers.

For legal reasons I somehow missed out on Laura Purcell’s debut The Silent Companions, but I was impressed by her second novel The Corset last year. In her third, Bone China, from Raven Books, she returns to a 19thcentury world of women trapped by rigid social restrictions and harsh judgements. Once again, Purcell skilfully maintains a complex, atmospheric twin narrative across two time periods and locations and the story convinces on the level of a modern understanding of psychology, disease and the effects of drug and alcohol abuse.

But Purcell also creates a dark, claustrophobic world where superstition and magical ritual exercise the power of life and death over its captives. The Cornwall of Bone China is a remote and brutal landscape that perfectly matches the guilt-ridden loneliness of the women exiled there.

I had so wanted to enjoy The Silent War by Swedish author Andreas Norman, published by Zaffre, or I should say enjoy it more, as the plot-line is intriguing. A disaffected MI6 officer contacts the head of Swedish intelligence in Brussels and leaks details of a very shady British operation (no, don’t worry, nothing to do with Brexit) in Syria. Our Swedish spy, Bente Jensen, reports back to her bosses in Stockholm who seem reluctant to act on the information, which is fairly explosive as it involves the torture of ISIS prisoners. Meanwhile, MI6 agent Jonathan Green, who is involved, perhaps reluctantly, in the Syrian operation, has his own problems mainly due to his affair with his departmental boss’ wife.

The book has the tag-line ‘Treason begins at home’ which is fair, as the first half of the book covers the disorderly private lives of these two spies, the British one cheating on his wife and the Swedish one being cheated on by her husband, and having to cope with a son with behavioural problems. Sadly, little sympathy is generated for these two central characters as neither seem particularly good at being spies.

My problem with the book – and this may just be me – is that I was constantly distracted from the narrative by the choice of language. A novel can certainly be ‘over-written’ but can one be ‘over-translated’? Schoolyard bullies are described as mirthful torturers; a cuckhold husband confronts his wife’s lover with the phrase ‘You don’t have many friends. Yet you piss on your chips like this’; an agent called back into the field is unpractised rather than ‘out of practice’; whisky is poured out by the dram; there is a tortuously detailed description of a boy playing keepy-uppy with a football; a character waiting for instructions fumes quietly As if he were a circus animal being kept in anticipation of the next number.

When we get to a bit of spy tradecraft, in London, the problem of urban geography raises its ugly head. Our MI6 agent is lodged in a safe house in Lambeth, ‘near the Imperial War Museum’. To meet a contact he first takes a taxi to Harrods in Knightsbridge to throw off anyone watching or tailing him and after trying on a shirt (!) and then buying one, he ‘takes the lift down to the car park’ (does Harrods have a basement garage?) and then ‘drives east’ in a car we didn’t know he had. After meeting his contact, a doctor in a hospital (no waiting for appointments here), he returns to the safe house in Lambeth. Then, bored, he defies orders and goes out for some fresh air and soon he is walking through the streets near Paddington…which according to Google Maps is a good hour-and-a-half trudge. What is more disconcerting is that, dying for a drink, he wonders Wasn’t there a pub near Warwick Avenue?

I should not blame Andreas Norman, whom I believe to be a former Swedish diplomat, for dodgy details of a foreign city – I would be rubbish describing a night out in Stockholm – but a British editor or translator might have picked up on a few points as, when a British spy can’t find a pub, we ought to realise we are in serious trouble.

Famous historical figures have long been pressed into acting as detectives in crime fiction, ranging from Ancient Greeks and Romans to Oscar Wilde, princes of Wales and first ladies of the United States.

This month Severn House publish two new novels with real people as detectives: Winter of Despair by Cora Harrison, which features Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins (a real pair of Likely Lads) teaming up to fight crime in Victorian England, and Script for Scandal, by Renee Patrick (husband and wife team Rosemarie and Vince Keene), set in the glamour days of Hollywood, which features legendary costume designer Edith Head as a sleuth.

A book not necessarily for this month, but rather December, where it would make an ideal stocking-filler for an Agatha Christie fan (there are only about 120 sleeps to Christmas after all) is Murder, She Said, [read the review here]a collection of quotes from Miss Marple edited by the indefatigable Tony Medawar. This pocket size volume comes with a 1928 essay by Dame Agatha on whether a ‘woman’s instinct’ makes her a good detective. Seemingly it does, or at least a good writer of detective stories. Don’t expect the Quotable Miss Marple to sparkle with Groucho Marx’s one-liners, or with Gore Vidal’s acidic put-downs, but for the dedicated fan, this will be a cosy, familiar read around the Christmas tree.

Brewing Up

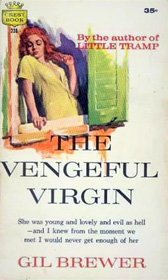

Another ‘revivalist’ publishing house, if I may coin that term, doing interesting work in the USA is Stark House Press who have just published Death Is a Private Eye, a collection of 22 previously unpublished stories by Gil Brewer.

Brewer (1922-1983) was a Florida-based writer firmly in the hardboiled ‘pulp’ genre, the titles of whose novels – such as The Vengeful Virgin and Gun the Dame Down – and their garish covers often detracted from his clever writing and willingness to tackle contemporary social issues.

Stark House have long flown the flag for Gil Brewer, whose fiction, if it was published over here at all, has long disappeared, although vintage paperbacks of French, Spanish, German and even Israeli editions of his novels can still be found.

Street Crime

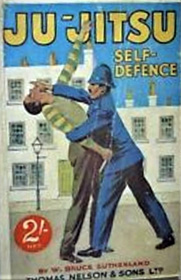

Our new Prime Minister, determined to stamp out street crime, has declared that the number of policemen, particularly ‘Bobbies on the Beat’ is to be increased. I have it on good authority that new recruits will be given the same training manual issued to the 1936 intake.

Angels Worldwide

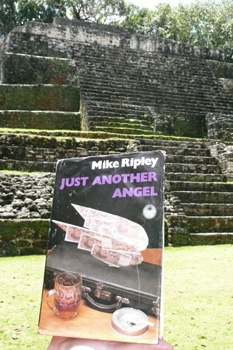

I am indebted to my South-East Asian correspondent, Jeff ‘Honourable Schoolboy’ Popple, for the following photographic evidence from the grounds of a temple at Siem Reap in Cambodia which purports to show what the fashionable tomb raider is reading these days.

Personally I have my doubts that this was actually left behind by Lara Croft on her last visit and it may be an attempt to recreate a famous picture from many years ago when a first edition of that very same book was found on the steps of a Mayan temple in Mexico, which the locals swore had been left by Indiana Jones.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster

|