|

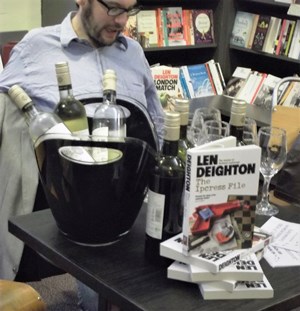

Gower Street Rules

The

spies have had it all their own way this summer on London’s Gower Street, with

a variety of events organised by Waterstone’s bookshop which have featured book club

sessions devoted to Eric Ambler, John Le Carré, Len Deighton and Elizabeth

Bowen (no, me neither) and contributions from contemporary spy writers such as

Mick Herron and Charles Cumming, with, along the way, honourable mentions for,

among others, Adam Hall, Peter O’Donnell, Dennis Wheatley, Anthony Price,

Francis Clifford and Alan Williams.

The

events were chaired by the erudite Jake Kerridge, noted crime critic of this

parish and my own modest contribution was followed by a splendid dinner party

made up of spy fiction fans and a group of devotees known unofficially as The Kiss Kiss Bang-Bangers for reasons which

escape me.

Sadly

an important foreign assignment will prevent me from attending the climax to

Waterstones’ Summer of Spies, their Spy

Mission and Top Secret Cocktail Party which will be held in the Gower

Street bookshop on Thursday 7th September at 8 p.m. Full details can be found at http://bit.ly/2gIdz55 and anyone planning on

attending is advised to make sure they are not being followed…

I

too will be keeping one eye over my shoulder whilst in foreign lands this month

as I will be reading an advance proof of the Lee Child’s new Jack Reacher

thriller The Midnight Line which is published by Bantam in November.

I

am well aware that many Reacher fans would go to inordinate lengths to get

their hands on such a treat, so I will be on my guard.

The Big Smoke

Whilst

trawling the jolly old interweb, as one does, I stumbled across the report of a

talk given at the 2013 Bloomsbury Festival by that most talented writer and

observer of London life, Cathi Unsworth. The subject of Cathi’s talk had been,

primarily, the 1958 thriller Trouble in West Two, a book which

was unknown to me and which I sadly discover (having been enthused by Cathi’s

assessment of it) is now incredibly rare.

Kevin

FitzGerald (1902-1993) wrote his thrillers in the 1950s and ’60s and with a

nice touch of self-depreciation, sub-titled most of them A Story for a Journey, much as

Graham Greene labelled many of his novels An

Entertainment. To be honest, I’d

never heard of Trouble in West Two but Cathi Unsworth’s recommendation that it

provided a nourishing slice of Bayswater sleaze whetted my appetite for more

insights into the London underworld of the 1950s.

To

satisfy my craving, I turned to one of Peter Cheyney’s lesser-known novels, Dressed

to Kill which appears to have been published posthumously the year

after Cheyney died. Cheyney (1896-1951) was a highly successful author who

dominated the British ‘hard-boiled’ scene, such as it was, from 1936 to his

death, much of his inspiration clearly coming from the American school of

gangsters, molls, gats and private eyes. Dennis Wheatley is said to have called

him ‘the greatest liar unhung but a magnificent story-teller’ and his influence

can be seen in the early James Bond books of Ian Fleming.

I

suspect that Dressed to Kill started life as a serial, for it is short, a

mere 149 pages, and although the hero is private eye, Rufus Gaunt, this is very

much a standard murder mystery of its day with all the tropes of establishing

alibis, tortuous coincidences, a murder which doesn’t happen and a suicide made

to look like a murder (which it is) and of course, the police distracted by the

trail of red herrings laid by the smart-aleck hero.

What

disappointed me most was the lack of any description of London life at the time

(1950?). Cheyney is so concerned with what he clearly thinks is a clever plot –

and, to be fair, he moves it along at pace – that there is little texture. The setting is supposed to be

Mayfair clubland and the characters go from one barely-described location to

another by taxi with only the odd street name thrown in as travelogue. Only one

particular piece of behaviour puts any flesh on the bones of basically

cardboard characters and that is smoking. A character, most often the hero,

lights a cigarette, puts out a cigarette (and usually lights ‘a fresh one’

immediately) or blows a smoke ring, on at least 48 of the 149 pages by my

count. Yes, I counted.

Prize Giving

Among

the storm of awards ceremonies and announcements of long and short lists for

them I discover to my surprise that the Crime Writers’ Association’s famous

Dagger awards are now sponsored by the excellent Crimefest convention (other conventions, I am told are available)

and a company called Hazchem, a mysterious international network run by an

oligarch with a fanatical devotion to crime and thriller fiction. (Other

oligarchs are available.)

I

have no idea how the CWA draws up its short lists for its awards and I am sure

all the books in the running this year are worthy contenders and in any case it

is not my place to comment, yet it is a mystery not to see Anthony Horowitz’s Magpie

Murders in contention for something. Perhaps an omission worth

investigating by Anthony’s wonderfully-named fictional detective Atticus Pund?

Thankless

Task

At the end of July crime critic and

freelance MC Jake Kerridge undertook a thankless task for the Daily Telegraph by recommending two British

crime novels from each decade starting in 1900. Thankless because, as with any

list, there will be dissenting voices arguing about the choice of titles and

because by strictly limiting himself to crime novels and excluding thrillers,

all the authors discussed at the on-going Summer

of Spies promotion (MC’d by Jake Kerridge, though other MCs are available)

fail to get a look in.

Having said that, I have few quibbles

with Jake’s pick of 24 novels “that defined their decades”. For the 1930’s

though I would certainly have included Francis Iles’ Malice Aforethought and

if one wanted to name a Michael Innes novel (and who wouldn’t?), then surely Lament

For A Maker is his tour-de-force.

For the 1960s, a decade dominated by

thrillers and spy stories, I would have hesitated before choosing Julian

Symons’ The Man Who Killed Himself, however it is quite difficult to

think instantly (though somebody will) of an alternative. John Le Carré’s A

Murder of Quality perhaps? Or the debuts of either P.D. James or Ruth

Rendell (though Rendell takes her rightful place in the 1970s)?

And much as I loved both the author and

the book, did Sarah Caudwell’s Thus Was Adonis Murdered really

“define” the1980s? It was, after all, the decade when Ruth Rendell became

Barbara Vine, when Ian Rankin popularised (rather than invented) ‘Tartan Noir’

and when John Harvey, with his Nottingham-based Charlie Resnick books gave us

ensemble cast policiers – perhaps the

nearest we have ever come to a British Hill

Street Blues. It was also the decade when Brits had a real go at exploring noir – not just Derek Raymond, but

Russell James and Mark Timlin – and when tough female detectives created by

Denise Danks, Val McDermid and Sarah Dunant laid the ground work protagonists

such as a certain girl with a dragon tattoo.

More Deadly Than

Beautifully

produced but as easy to handle as a Gutenberg Bible, Deadlier is a 1007-page

anthology of short stories (a hundred of them) selected by Sophie Hannah, which

will be published in October by Head of Zeus.

All

the stories are written by women and all the usual suspects are there when it

comes to female crime writers, who seem to be primarily British and one or two

who may be new names. Surprisingly there is no room for P.D. James, Sara

Paretsky, Catherine Aird or Jessica Mann who, in a sense, wrote the book on the

subject with her study Deadlier Than the Male in 1981, nor

Martina Cole, who must be Britain’s most successful living female exponent of

the crime genre.

Books of the Month Club

Much

as I am sure the publishers would like it to be in terms of sales, When

I Wake Up is not actually the follow-up to S.J. Watson’s 2011

best-seller Before I Go To Sleep.

It

is in fact the debut novel of Jessica Jarlvi, published by Aria, a new imprint

of Head of Zeus, and is set in small town Sweden (Jarlvi was born in Sweden but

has since lived in England, the US and Dubai) where a much-loved local teacher

and mother-of-two is left in a coma after a savage beating. The police

investigation, and that conducted by her husband, uncover, wouldn’t you know

it, that teacher Anna has been leading a secret life and when Anna does ‘wake

up’ things get even more complicated. For fans of ‘Domestic Noir’ and ‘Nordic

Noir’, this is one-stop shopping and is sure to do well.

For

a burst of the finest ‘noir’ in its purest sense (where you know from page one

that it isn’t going to end happily) in what is one of the most impressive debut

crime novels of the year, look no further than Last Stop Tokyo by James

Buckler, now out from Doubleday.

Like

the best ‘noir’, the two main characters are far from perfect if not actually

damaged, both are seeking to escape past nightmares, there are

misunderstandings, double-crosses galore and plot twists designed by a master

corkscrew maker as a lost (in more ways than one) Englishman flees to Japan to

make a new life. But Japan is not the easiest place

for a foreigner trying to fit in and find love with an ambitious local girl and

our Englishman abroad soon runs head-first into the solid wall of Japanese

morals and traditions, not to mention a powerful local crime syndicate. Last

Stop Tokyo is clearly written by someone with first-hand knowledge of

Japan and a flair for telling a serpentine story.

Nobody

does the bad old days better than Paul Doherty; the bad old days in this case

being the squalid, gang-controlled dockside slums of Queenhithe in London

(south of St Paul’s where today the Millennium footbridge is) back in 1381.

When

a priest is murdered in his own (locked) church there, and the church money box

found empty, it is clearly a case for Dominican friar and talented sleuth

Brother Athelstan who has to immerse himself into the bubbling swamp of

gangland crime and violence and discover the secrets of The Mansions of Murder, his

latest adventure now out from Severn House.

This

is medieval England red in tooth and claw, packed with bizarre, but probably

historically accurate, characters such as an evil publican known as The Flesher

(and we’ve all known one like that), Moleskin the boatman, Ranulf the

rat-catcher and Daniel the Damned, who would bite the head off a live rat for a

penny (steady work in those days, and well paid!).

Doherty

writes fiction but teaches history along the way and from this novel alone I have

learned that in the 14th century, a ‘sneaksman’ was a thief, Newgate

Prison was known as ‘Cramp Abbey’, a ‘dilp’ was a lady of loose (if any) morals

and the powerful underworld gangs who ran the whole show were ‘rifflers’. It

just goes to show that even when engrossed in crime fiction, every day is a

school day.

Book of the Next Month Club

The small, but perfectly formed, Scottish publisher Saraband and its crime imprint Contraband, had a smash hit on its hands with Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, the Los Angeles Times’ Book Awards and goodness knows how many others (though curiously none of the Crime Writers’ awards). Burnet’s new novel, eagerly anticipated, hits the bookshops in October and whilst it also adopts what one might call a ‘found footage’ approach if talking about a film, the setting is a world away from the harsh 19th century Scotland so brilliantly conjured in Bloody Project.

The Accident on the A35 is a modern psychological thriller set in a small French town near Strasbourg, and not as I first assumed on that scenic highway so popular with caravaners which runs through Dorset.

I have only had time to take a sneaky peek, but my immediate reaction is “prime Simenon territory.” I think Burnet and Saraband have done it again.

Book of the Next Year Club

I know there are some reviewers who positively fume with annoyance when publishers send out review copies of new novels six months in advance, as opposed to the fits of raging frustration when one arrives the day after publication (or the expletives which ring out when a publisher insists on a hypothetical embargo). However, I cannot be anything but grateful for the personalised, signed proof of Jane Harper’s follow-up to her best-selling The Dry I have just received.

Muggles and other mortals will, I am afraid, will have to wait until 1st February 2018, when Force of Nature is published by Little Brown.

|

|

Gone Fishing

I had not fully appreciated – if I ever really knew – just how versatile a writer American Robert L. Fish (1912-1981) was.

Best known on this side of the Atlantic under the pen-name Robert L. Pike for his 1963 novel Mute Witness, which became even better known when it was filmed as Bullitt starring the ultra-cool Steve McQueen and a ground-breaking (not to mention suspension-breaking) car chase.

Real mystery fans will also be aware of his series of mysteries starring Captain Jose De Silva, set mostly in Brazil, his spoof ‘Shlock Holmes’ (and ‘Dr Watney’) parodies and perhaps even his European novels featuring smuggler Kek Huuygens operating out of Belgium in the years immediately after WWII. Dedicated pub-quizzers might also recall that he ghosted the autobiography of footballer Pele, published at least one volume of poetry, wrote thrillers involving missing Nazi treasure hordes, edited anthologies for the Mystery Writers of America and completed Jack London’s unfinished novel The Assassination Bureau, which was also filmed in the Sixties starring Oliver Reed and Diana Rigg or ‘Mrs Peel’ as she was commonly known then rather than Lady Olenna Tyrell (recently deceased).

I have now come across another product of Mr Fish’s prolific pen, The Murder League, first published in the US in 1968 and which made it into paperback over here in 1970. Although set in London and clearly written in homage to a blackly-comic version of the ‘Golden Age’, the British edition makes no attempt to correct American spellings or some howlers about British life, particularly when it comes to drinking! In the London of The Murder League, whiskey (sic) is sold in ‘pint bottles’ and in a pub, beer is always served in pewter tankards or ‘flagons’ by buxom wenches waiting on tables.

Such petty carping aside, Murder League is an excellent read; clever and darkly humorous given the premise: a trio of ageing crime writers well past their publication sell-by date decide to put their accumulated fictional knowledge to good use and offer their services as professional assassins – discretion guaranteed. Their aim is to perform ten ‘hits’ at £1,000 a go and then retire from the homicide business. All goes well until the tenth contracted murder (they advertise in The Times!) leads to one of the League being arrested and brought to trial. Only the most brilliant defence lawyer in the country can get him off – and he does, but his fee (for he is a sharp cookie) is – you’ve guessed it - £10,000.

It’s a wonderful romp, with many a sideswipe at the snobbery and pretentiousness of the English and a few at the gaucheness of Americans, plus a lovely vignette of a policeman struggling to understand the new-fangled computer thing which Scotland Yard have just bought from IBM. I would not jump on the popular bandwagon and claim that The Murder League is a ‘forgotten classic’ but it is certainly a forgotten delight. And as an added treat, I have discovered there were two further adventures featuring the old codgers of the ‘Murder League’ (who, for legal reasons, in no way remind me of members of the Crime Writers’ Association): Rub-A-Dub-Dub (1971) and A Gross Carriage of Justice (1979), which I am busy tracking down.

Spy Gals

My old and distinguished friend Randall Masteller, over in the great (and very beautiful) state of North Carolina runs an encyclopaedic website called Spy Guys and Gals dedicated to spy fiction and I hope he does not mind me appropriating half his title to highlight the fact that spy stories are still with us and more and more seem, at last, to be being written by women.

The regular reader of this column (we know where you live) is well aware that I am a great fan of the work of Aly Monroe and Elizabeth Wilson as well as the legendary Helen MacInnes, who so often ‘flew solo’ as the only female spy-writer anyone could think of. Now I can name two others.

Dolores Gordon-Smith is well-known as a crime-writer, and one with a flair for 1920s’ settings, but with The Price of Silence (Severn House) the action is set firmly during the First World War, and although the book begins as if it is going to be a murder mystery (three victims, two in a locked room), it soon develops into a John Buchan-esque adventure involving our hero (a scrupulously honourable military doctor) going undercover in German-occupied Belgium before the action returns to England and, after some good spy tradecraft, a dramatic shoot-out on the Kent coast with the inevitable U-boat lurking off shore.

It’s jolly, fast-paced spy stuff and the villains are nicely ruthless, providing a quite high body count, and if I have a qualm, it is that the plot revolves around an orphan girl who featured in a previous novel, Frankie’s Letter, published in 2012, and not having read that I felt I was missing something.

A new name to me and I suspect to anyone who doesn’t read the New Yorker or live in Berlin, is Sally McGrane, an American journalist who works out of Germany, whose debut novel Moscow At Midnight is published by Contraband and is a brilliant example of how modern spy fiction can adapt despite minor distractions such as the Cold War ending and the Berlin Wall coming down.

Downsized by the CIA, agent Max Rushmore is hired on a freelance basis partly on his reputation for being able to drink most Russians under the table and sets off across Russia in search of a missing (presumed dead) nuclear waste disposal expert. The question is where is the nuclear waste coming from and what is the significance of a fabled ‘Siberian diamond’? It’s helter-skelter stuff with multiple layers of confusion abounding – so many, you suspect this really is espionage in the post-Cold War age.

A spy story written by an Irishman set in a Russian coal mining outpost in the Arctic in 1977, proves the John Le Carré maxim that “as with love stories, the possibilities [of the spy story] are limitless.”

The Reluctant Contact by Stephen Burke, published by Hodder this month, uses the bleak, Arctic setting of the Svarlsbad archipelago not for a thriller about Nazi U-boats or secret scientific research centres (both of which have been done in the past) but rather a small-scale case of the defection of a dissident from Soviet Russia, via the mining community at Pyramiden established on what was, in effect, Norwegian territory. It is, also in the Le Carré tradition, essentially a love story, examining the relationships between a small cast of characters juggling personal and political emotions.

If a little low on violence and suspense (given the wild setting) for those who like their thrillers stuffed with blood-and-guts action, The Reluctant Contact contains some fine character studies, well-worked plot twists and shows how the Cold War impacted on individuals in a place of permanent cold.

The Writer’s Life

Crime writers – don’t you just love them when they talk about the writing process? (Do I not know what ‘rhetorical’ means?) With two new titles come fascinating peeps behind the curtain of the writer’s methods and motives.

Some months ago, I met the charming Canadian Linwood Barclay for lunch and learned about the publication, from Orion, of his four early comic thrillers (before he became far more successful with scary thrillers) starring Zack Walker which are coming out in the UK under the titles Bad Move, Bad Guys, Bad Luck and Bad News. The Zack Walker books were written between 2004 and 2007, before Linwood’s international bestseller No Time For Goodbye, but only published in North America.

In an introduction to the first of the new issues, Linwood explains the genesis of his ex-newspaperman hero: Zack…is a quirky guy. He’s an anal retentive, obsessive compulsive, anxiety-ridden individual, and I hate to tell you who he’s based on. He is, essentially, me unchecked…Given his fearful nature, Zack is the most poorly equipped person on the planet to go up against bad guys.

Having met Linwood, I don’t believe a word of that, but the books are tremendous fun.

The latest novel by Australia’s ‘godfather of crime fiction’ Peter Corris, Win, Lose or Draw (Allen & Unwin) comes with the sad news that it will the 42nd and last case for detective Cliff Hardy, and indeed the last book for the 75-year-old author.

In a press release accompanying advance copies of the book, Corris tells of his struggle with failing eyesight resulting from a long-term diabetes condition and poignantly relates how ‘three or four books back’ he began to write in 18pt type on his computer but now has had to increase the type size to 36pt. He considered, but rejected, the idea of dictating as he ‘loved seeing the words appear on the screen’ and ‘anything else wouldn’t feel like writing’.

Corris is also very aware of the amount of time it took him to complete a novel. Recently, a book has taken ‘two to three months’ to finish (which is, most would feel, damn good going) ‘rather than a month and a half as in the past’ (!) and when he started Win, Lose or Draw, he had no idea it would be his last. In fact, the book has an upbeat ending for detective Cliff Hardy (who first appeared in 1980), but there is no doubt that he – and Peter Corris – will be sorely missed from the crime scene.

Cover Girls

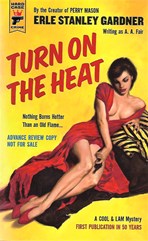

Hard Case Crime, an imprint here of Titan Books, has a splendid record in publishing (or republishing) some forgotten gems of crime fiction and have never been ashamed of their ‘hard-boiled’ and ‘pulp’ heritage, as they have shown with their flair for wonderfully garish cover art.

Their latest reissue, first published in 1940, is Turn On The Heat which was the second in a series of mysteries to feature the private detective duo of Donald Lam and Bertha Cool (though better known as ‘Cool and Lam’), written by the staggeringly prolific Erle Stanley Gardner under the pen-name A.A.Fair.

The ultimate odd couple to be partners (ultimately) in a detective agency, Bertha Cool was an overweight, greedy sixty-something with a miserly attitude to life, whereas Donald Lam was, well, a bit wimpish, yet they survived as a partnership for some two dozen novels from 1936 to 1970, though I suspect they were far more popular on the other side of the Atlantic than they were here. Certainly, ‘Cool and Lam’ never become the household name that ‘Perry Mason’ did.

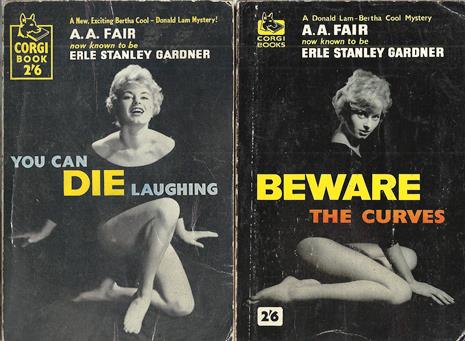

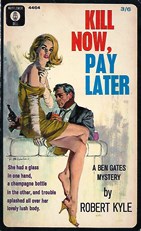

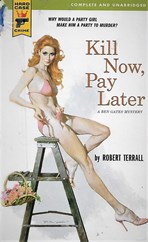

And lest anyone think that the new Hard Case edition is going slightly over the top with a femme fatale cover, this is how Corgi paperbacks introduced the series to the UK more than fifty years ago in 1958:

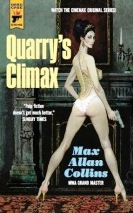

For the new Max Allan Collins’ novel Quarry’s Climax, which features his 1970s Vietnam-hardened professional assassin, Hard Case have gone to the best when it comes to pulp art, with an original cover from the legendary Robert McGinnis, now at the venerable age of 91.

One of McGinnis’ famous covers, originally for the 1960 Robert Kyle thriller Kill Now, Pay Later, recently adorned the back cover of a well-received homage to British thrillers of the period 1953-75 (though modesty prevents me from elaborating). When Kill Now, Pay Later was reissued in 2007, Hard Case Crime went back to the source and commissioned Robert McGinnis for another original cover painting.

Whilst I admire Hard Case Crime’s general sense of style (however politically incorrect), I have to admit to bias and mercenary self-interest and say that I much prefer Mr McGinnis’ original concept.

Carry on Up the Amazon

It is hard to believe it if coming up to 30 years since I read the first of Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus novels, Knots & Crosses, and am delighted to learn that at the recent Edinburgh Book festival, Ian announced that there would be another Rebus tale in November 2018.

To my dismay, I cannot find my copy of Knots & Crosses and so turned to Amazon looking for a replacement only to find that a more recent reader, in 2016, had reviewed the book and, inexplicably, given it only one star in a review entitled ‘Histrionic poor policing’. Not quite believing my eyes, I determined to find out what else this anonymous ‘Amazon Customer’ had reviewed and discovered that he or she was actually quite fond of handing out poor reviews, giving a scathing one star to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, Romanoff Caviar Black Lumpfish and a battery-operated Women’s Shaver and Nose-Trimmer. Only one recent purchase seemed to merit a five-star glowing review, that of a set of wood-burning pens, with ‘Amazon Customer’ reporting proudly ‘I have been wood burning and branding for nearly ten years’, though that does not explain the grudge he or she clearly holds for writers of very popular fiction who live in Edinburgh…

I do hope that next year’s Rebus novel includes something unspeakable involving a wood-burning pen or a ladies’ nose-trimmer.

Tinkety Tonk!

The Ripster

|