SITE CONTENTS

|

|

|

ISAAC

ASIMOV |

| THE BLACK

WIDOWERS: Overlooked but not Forgotten |

| by Catherine D Stewart |

|

ISAAC ASIMOV is one of the greatest science-fiction

writers of the 20th Century but his role as an acclaimed mystery

writer is often overlooked. To redress this balance, we celebrate

possibly his most popular sleuths - The Black Widowers.

Like all the best fiction, The Black Widowers are based on fact, a

real-life organisation called The Trap-Door Spiders, of which Asimov

was a member.

Isaac Asimov was born in Petrovichi, Russia, on 2nd January 1920.

In 1923, the family emigrated to the United States, settling in

Brooklyn, New York where Isaac became a U.S. citizen in 1928.

Rightly acknowledged as a master of science-fiction, Isaac's

childhood was nevertheless grounded in mysteries, much of his time

spent purloining his father's forbidden copies of The Shadow, which,

according to Asimov, his father insisted he read because, 'he needed

to learn English, whereas I had school - and what a rotten reason I

thought that was.'

When Word War II began in 1939, America took an isolationist

stance. A decade of poverty and deprivation left an insular nation

vastly unwilling to sacrifice its youth in a war somewhere much of

its population had never heard about. On 7th December 1941, Pearl

Harbour and the death of 3,000 Americans led to the United States

entering the war with a vengeance. Isaac Asimov joined the U.S.

Navy, though he saw little action. He was mostly stationed at the

U.S. Naval Air Experiment Station, where his fellow soldiers

included sci-fi giants-to-be Robert A. Heinlein and L. Sprague de

Camp. The latter became a lifelong friend of Asimov, and is

immortalised in the Black Widowers character Geoffrey Avalon. In

1942, Asimov married, his first wife, Gertrude Blugerman and, after

his discharge, he returned to his studies, getting a Ph.D. in 1948,

obtaining the post of Assistant Professor in Biochemistry at Boston

University.

Just 2 years later, Pebble in the Sky hinted at the greatness to

come although Asimov's first published work had been in the magazine

Amazing Stories eleven years earlier when he was 19. In 1950, he

also published his sci-fi short story, I, Robot. It was the first

instalment of his seminal Foundation saga, possibly his most famous

work. A year later, The Stars Like Dust was published. Despite the

demands of a family, Asimov was able to become a full-time writer.

During these decades, his output can only be called "extraordinary".

In his lifetime he published over 500 works (bested only by Enid

Blyton's 600+). He seemed to have one book for every section of the

Dewey decimal system - Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry etc. He also

wrote junior fiction, firstly under the pseudonym of Paul French,

and later (including Norby the Mixed-Up Robot) under his own name

with his second wife, Janet Opal Jeppson, the

psychiatrist-turned-authoress whom he married in 1973.

Crime

played little part in this outpouring of science-fiction genius,

most of his works were either pure science-based fiction or

non-fiction. Part of the problem is the natural human tendency to "pigeon

hole" a person according to what they achieve first. His only "mystery"

story during this era, A Whiff of Death (Doubleday 1958), dealt

solely with science and scientists, emphasising his role as a

science-fiction writer. Crime

played little part in this outpouring of science-fiction genius,

most of his works were either pure science-based fiction or

non-fiction. Part of the problem is the natural human tendency to "pigeon

hole" a person according to what they achieve first. His only "mystery"

story during this era, A Whiff of Death (Doubleday 1958), dealt

solely with science and scientists, emphasising his role as a

science-fiction writer.

However, in 1953, Asimov wrote The Caves of Steel, a murder-mystery

set in the far future, where the hero was a New York police

detective named Elijah Bailey. Out of favour with his superiors,

Bailey is ordered to solve the impossible murder of Dr Sarton, a

Spacer [the technologically superior Earth descended colonists who

beat Earth in an ancient war and now rule the galaxy] and is even

assigned the man's creation, Robot Daneel Olivaw [Daniel Oliver] as

a partner. Daneel looks perfectly human, but robots are hated on

Earth and routinely destroyed, placing Bailey in a precarious

position. Despite the obstacles in his path, Bailey solves the crime

when he discovers that Dr Sarton created the robots in his own

image, and the killer's target was not Sarton, but Daneel. The story

was such a success that Asimov wrote two sequels, The Naked Sun and

The Robots of Dawn, plus Robots and Empire, set 200 years later and

involving Bailey's descendants along with Daneel Olivaw.

Nevertheless, the books were still classed as science-fiction. The

Bailey series was used to highlight many of Asimov's theories on

robotics and artificial intelligence, and they are rightly viewed as

ground-breaking works even though roboticists today reject Asimov's

famous Three Laws because they would prevent robots from serving in

the very areas humans would most desire: as soldiers, law

enforcement or rescue personnel. A point tragically highlighted on

11th September 2001, when the New York Police and Fire Department

each lost nearly 300 people in the attack on the World Trade Centre.

Asimov's other great worry was over-population, perhaps a result of

seeing the large families in the Brooklyn tenements starving during

the Depression. He used the Bailey books as a platform to warn of

the danger of unsustainable population growth. Arthur C. Clarke is

often called a "prophet" of modern science in his early

fiction, but Asimov was equally as perceptive in some areas, the

only difference being that Clarke put most of his ideas in one book,

2001: A Space Odyssey, whereas Asimov shared his over several books.

However, despite the mystery element of the Bailey series, it was so

well received as science-fiction that author Roger McBride Allen

completed it after Asimov's death by writing the novels, Caliber,

Inferno and Utopia.

But Asimov still craved to write "straight" mysteries.

Partly he hesitated because, to quote the man himself, 'Mysteries

these days are heavily drenched in liquor, injected with drugs,

marinated in sex and roasted in sadism, whereas my detective ideal

is Hercules Poirot and his little Grey cells.'

Things changed when, in the 1940s, a couple married, only for the

husband's friends to be unacceptable to the wife and vice versa.

Unwilling to relinquish the relationships, the husband and his

friends founded a male-only club, called The Trap-Door Spiders. They

would meet monthly, always on a Friday night, usually in a Manhattan

restaurant or, more rarely, a member's home. Two co-hosts bore the

expenses of the evening and, as such, were each entitled to bring a

guest. The average attendance at each meeting was about 12 men.

Membership entitled one to the honorific title of "Doctor",

and each member was supposed to arrange a mention of TDS in his

obituary. The club was an outstanding success, continuing long after

the founder's divorce rendered it unnecessary, and as far as it is

known, it is still going strong in 2001. Asimov himself had been a

guest twice, and then, in 1970, he and his wife Gertrude Asimov

separated. Isaac Asimov returned to live in New York where The

Trap-Door Spiders promptly elected him to membership of the club. He

was also a member of The Baker Street Irregulars Sherlock Holmes fan

society, and this would provide a later Black Widowers story, The

Ultimate Crime.

A few months later in 1971, Eleanor Sullivan, Managing Editor of

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine [EQMM] asked Asimov to write a short

story for them. He was provided with a plot by his friend, actor

David Ford, who told Asimov that he was convinced someone had once

stolen something from his apartment, but he could never be sure

because the place was crammed with all sorts of collected but

uncatalogued oddities, thus there was no hope of telling if anything

was missing.

TDS provided Asimov with the ideal setting. He changed the name of

the club to The Black Widowers, took the average number of attendees

and halved it to a more manageable six, setting the stories at a

Manhattan restaurant named Milano's with only one host and one

guest. The only fictional character in the stories is the waiter,

Henry, who has a soupçon of Jeeves about him, all the others

being based on real people (recognisable to sci-fi aficionados) who

kindly lent their likeness to Asimov. They were:

Character based on Geoffrey Avalon - L. Sprague de Camp

Emmanuel Rubin - Lester del Rey

Roger Halstead - Don Benson

Mario Gonzalo - Lin Carter

Thomas Trumbull - Gilbert Cant

James Drake - John D. Clark

|

|

The first story was entitled The

Acquisitive Chuckle and was published by EQMM in 1971. In it,

the evening's guest, Hanley Bartram, is a private investigator

who failed to solve one case and recounts it to the Black

Widowers. Two men, Anderson and Jackson, became business

partners and initially the venture was successful. Jackson was

so pathologically honest - honour permeated his soul to the

point that it was as if 'he had been marinated in integrity'

from infancy - that he became the public face for the company,

whilst Anderson, who was as unscrupulous and unethical as his

partner was honourable, looked after the money which was his

area of expertise. |

But problems arose: Jackson's immense integrity meant Anderson was

sometimes pushed into situations where he lost money, while

Anderson's greed meant Jackson was sometimes placed into situations

of dishonourable practice. Since Jackson hated losing character, and

Anderson abhorred losing money, their relationship deteriorated

until Anderson managed to force Jackson to sell him his half of the

business under the most disadvantageous of circumstances, leaving

Jackson virtually penniless. Bartram was hired by the furious

Anderson on a considerable retainer to find something he claimed

Jackson had stolen. Anderson was acquisitive, a collector of all

sorts of oddities and bric á brac that he stored in the large

mansion that also served as his office and home.

Jackson had sworn revenge after the dissolution of the partnership

and one night, Anderson arrived home to find 'honest' Jackson in the

mansion; Jackson claimed to be returning some papers and the office

key, which he did, before closing his old attaché case and

leaving. As Jackson closed the door behind him, Anderson heard him

chuckle, a chuckle Anderson, with thirty-plus years of acquisition

knew. It was the chuckle of a man who had just obtained something he

wanted very much at the expense of someone else.

Furious, Anderson knew Jackson had stolen one of his oddities and

was determined to retrieve it. However, like David Ford's apartment,

his mansion was crammed with all sorts of junk, most of which was

small enough to fit inside an attaché case. Anderson had no

idea what he possessed and what he didn't. Despite five years of

trying, Bartram had been unable to discover what Jackson had stolen

that day. The denouement comes when Bartram introduces the Black

Widowers to their waiter, Henry Jackson. Henry still was a

pathologically honest man - what his carefully choreographed revenge

enabled him to steal from Anderson that day had not been material

treasure, but Anderson's peace of mind - Anderson going to his grave

in the belief that Jackson had outwitted him.

Asimov intended the story as a one-shot, and it might have ended

there, had it not been for Frederic Danny, one of the two authors

who formed 'Ellery Queen'.. Dannay firmly believed that the story

would make an excellent series and encouraged Asimov to keep writing

them, which he did, although Dannay, who died in 1982, did not live

to see the later ones.

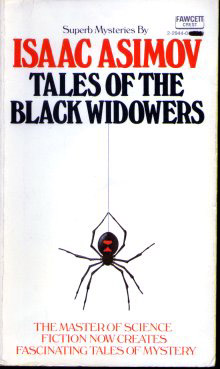

Periodically after serialisation, the stories would be collected

into one anthology. There were five books which contained twelve

stories each: Tales of the Black Widowers, More Tales of the Black

Widowers, Casebook of the Black Widowers, Banquets of the Black

Widowers and Puzzles of the Black Widowers. The stories are

definitely cerebral as opposed to the "three bodies per chapter"

type. The opening story has the reader trying to figure out what

items would fit into a small attaché case, and the twist

where Jackson steals only Anderson's peace of mind is wonderful.

Only one story, Early Sunday Morning (Tales of the Black Widowers)

deals with murder, and then from a perspective of three years'

distance. Nothing Like Murder (More Tales of the Black Widowers) was

a tribute to the fantasist J. R. R. Tolkien, who died in 1973,

although the story has nothing to do with murder. The stories can

sometimes be repetitive in setting - originally written as serials

for EQMM, Asimov had to reiterate names, features and

characteristics for the benefit of new readers and as reminders for

old ones. His copy editor helped him to eliminate the more tedious

examples, but those that are left are well worth putting up with

considering the general excellence of the stories.

The fact that Asimov was a bona fide scientist was his greatest

strength as a sci-fi author, but was of less of a benefit to him as

a mystery writer. Sometimes he got too involved with his obsessions

or some obscure scholarly point. Asimov was extremely anti-religious

(especially Christianity) and attacked religion in his stories in

ways that were 'often [so] subtle the [usual] reader may never

notice.' (Michael Hammond, Religion in Asimov's Writings). Some may

argue that he should never have written them - the whole point being

that the reader should be able to follow what the author is saying.

Asimov wrote in such wide areas of literature that he often got

letters saying, "why do you, a Shakespearean scholar, write

science-fiction?" or, "why do you, a biochemist, think you

know anything about Shakespeare?" This erudition gave him

masses of material for his stories, but it also meant Asimov could

write at too high a level for any but a specialist to understand. An

example of this is the "solution" to the Black Widowers

story Truth to Tell, which hinges on an extremely obscure point of

linguistics and which would probably only be amusing to a

linguistics professional.

His prejudice against religion in general intrudes into the Black

Widower story The Obvious Factor, where Asimov sets up the story so

there can only be a supernatural solution, only to have the

protagonist cheat and admit he made it up - a cop-out ending similar

to the "with a single bound he was free" cliché.

Such actions ruin our "suspension of disbelief", our

ability to lose ourselves in the story.

Asimov's anti-religious snippets can be irritating in his works,

especially in the shorter tales like the Black Widowers, but they

are well worth taking with a pinch of salt and the astute reader

will not let them detract from what is otherwise excellent

story-telling. For those really annoyed however, keep in mind that,

for all his protestations and sarcasm about those with open

religious beliefs rather than hiding what they were, Asimov himself

was religious - Science was his god; he simply cloaked his worship

with phrases like "rationalism" and "humanism".

He was also lured into pseudo-sciences like psychohistory.

What the Black Widower stories accomplish so well is that they are

intriguing. Like all the best puzzles they have the reader cranking

up the "little Grey cells" in an effort to outwit Asimov's

denouement at the end of the story, and they are challenging..

Perhaps most importantly, they got Asimov's own "little Grey

cells" working too.

The first Black Widower story was in 1971, and after his two

previous abortive attempts at murder-mystery fiction (A Whiff of

Death, 1958 and Asimov's Mysteries, 1968), they helped him to become

an accomplished crime writer as well as a prolific one. The novel,

Murder at the ABA was published in 1976. Whilst, as well as the

Black Widower anthologies (1974, 76, 1980, 84, & 1990) he wrote

several other short-story mystery anthologies [The Key Word &

Other Mysteries (1977); The Union Club Mysteries (1983); The

Disappearing Man & Other Mysteries (1985) and The Best Mysteries

of Isaac Asimov (1986)] all of which were published in the 21 year

period from the first Black Widower story in 1971 to Asimov's death,

aged 72, on 6th April 1992 He also wrote the junior fantasy-mystery

novel, Azalea in 1988 and would have continued the Black Widowers

had he lived - we must therefore mourn for the mysteries they, and

we, never got to solve.

The Black Widowers have not achieved the same heights of fame as

Asimov's science-fiction works, such as Foundation or the Robot

series, and this is regretful, for they are well-written, highly

enjoyable examples of just how good a mystery writer Isaac Asimov

was.

© 2001 C. D. Stewart

|

|