|

|

|

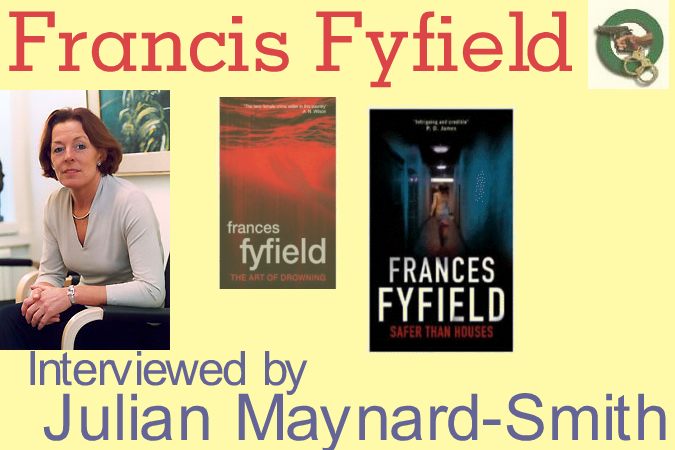

Frances Fyfield’s novels include A Question of Guilt, nominated for an Edgar Award, Deep Sleep, winner of the Silver Dagger Award, A Clear Conscience, nominated for the Gold Dagger Award and winner of the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 1998, Shadow Play and Blind Date. Her penultimate book is Safer Than Houses, the latest in the Sarah Fortune series, which was shortlisted for the Duncan Lawrie Dagger (formerly known as the Gold Dagger). Her latest, The Art of Drowning, has just been released in hardback (6 July 2006). The title Safer Than Houses is obviously ironic, in that the major thread to the story is the damage that can be wreaked when someone covets another person’s property. Did your research into the forensics of fire investigations affect the plot? And did the title inspire the story, or vice versa? The title always arrives at the very end of a story for me. It’s ironic, because although it’s a lovely phrase, houses are not safe. The research did influence the plot, which came to mind when I was making a Radio 4 programme in a series called Footprints, one of which followed the work of a fire investigator. Just when you feel safe... A number of the characters in Safer Than Houses have moral compasses whose needles are bent but still manage to point in the direction of goodness: for example, Sarah Fortune, who’s gone from lawyer to ‘tart with a heart’; Alan, the arsonist with a conscience; and Dulcie, who’s quite happy to bend the interpretation of a will to redress an earlier injustice. And as a criminal lawyer, you must have come across morally ambiguous characters. Have any real-life cases you’ve dealt with informed your novels? And do you personally believe there are any moral imperatives, or that all morality is subjective and relative? I think there are moral imperatives, which very roughly correspond with the ten commandments of all major religions, thus, Thou shalt not steal, kill, covet, and none of them apply in extremes of war, poverty, starvation and riches. I have met more morally ambiguous people in normal life than in a life of crime. Most people have a moral code, albeit beset with prejudice. I like to write about people who cannot avoid being kind, whatever else they do. Readers have followed Sarah Fortune’s fortunes (so to speak) across four novels so far: Perfectly Pure and Good, Staring at the Light, Looking Down and now Safe as Houses. With a Sarah Fortune omnibus due out next year, are you ready to ‘retire’ Sarah, or do you have further stories in mind for her? At the end of Safer than Houses, Sarah F announces her intention to carry on as before. She and I have unfinished business. I’m interested to see what she does next, but I don’t know when. What different challenges are presented by standalones versus series, and do you have a preference? I like standalones best. I want series characters to retire before they get exhausted and I always want a new challenge. The name ‘Sarah Fortune’ sounds loaded with symbolism – and in The Art of Drowning we have ‘Ivy’ with its suggestion of insidious parasitism, and ‘Grace’ with its (in this case ironic) suggestion of forgiveness. Were these names conscious choices? And does symbolism play a role in how you conceive your novels? The names were conscious choices because they are rather old fashioned and I like them, and if you’re going to write a name again and again, it’s better to like the sound of it. Sarah is a name I’ve always liked; Fortune was the name of a neighbour. Rather than symbolic, Grace is a name which would have been used often in her generation; Ivy is fanciful. So no, no conscious symbolism. Characters just turn out to suit the names they have. In The Art of

Drowning, Ivy is both obsessively loving and hating, with no shades of grey in

between. In contrast, Rachel is helplessly naïve, willing to explain away all

the evidence stacking up against her new best friend and flatmate. The plot

seems almost fatalistically determined by the collision of these two lives, like

something from a Greek tragedy. Do you find your characters are driving the

plot, or does your plot drive the characters? Or are the two inseparable? The characters drive the plot, and me. What fascinates me is how the collision of two people can make them both better or worse. Ivy’s ex-husband Carl, a judge, is a model of rectitude and emotional restraint. Ivy and he are almost like two facets of one personality: one pure id, and the other pure super-ego. Do you find yourself consciously separating, then exaggerating, aspects of your own personality when creating your characters? Yes. There is a part of me (or what I would like to be) in all of them. I’m Carl and I’m Rachel, and I’d always be vulnerable to an Ivy. Your first novel, A Question of Guilt, was first published in 1988. How do you feel your writing has evolved over the past two decades? And are you conscious of any particular themes or ideas that you’re constantly drawn to? I hope the writing has got better. The only theme I have constantly returned to is how nothing is quite what it seems, and judge not that you may not be judged. I have learned not to compromise. Of your writing, PD James has written: ‘There are crime writers whom we think of primarily as novelists … There is no one higher on this list than Frances Fyfield.’ High praise indeed. With several crime novelists now upping the literary ante, do you think there is any validity to the ongoing distinction between ‘crime fiction’ and ‘novels about crime’? If so, what do you feel are the distinguishing characteristics? I wish there were not a division between genre fiction and mainstream. I’m a novelist first and a crime writer second, because all novels, to me, are about relationships and their results. The only difference between a crime novel and a mainstream novel is that death, or the fear of death, is at the heart of it, and it can’t be self indulgent. It must tell a good, strong story, which is all I ever wanted to do, but in excellent, vivid prose. ‘Crime fiction’ is associated with second rate writing. It should not be. What are you working on now? God alone knows, but this is as far as it’s got. There was this successful woman who threw herself out of a high window, and no one knew why she had done it. There are five possible reasons, apart from the obvious. A crisis of conscience, shame, a love affair, greed? I don’t know; I never do, but she’s haunting herself into my life and I’m beginning to like her.

|

| Webmaster: Tony 'Grog' Roberts [Contact] |