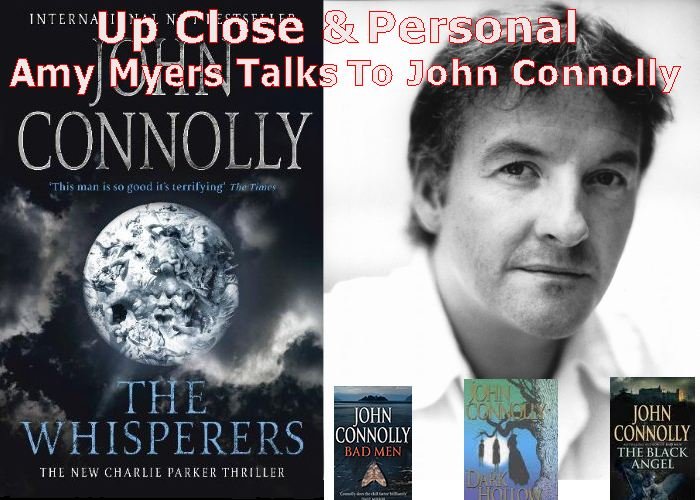

The

Whisperers

(Hodder

& Stoughton, hardcover, £17.99, 13

May 2010)

is the ninth in John Connolly’s best-selling Charlie Parker

series, which began

with Every

Dead Thing in

1999. As a Times

review

said of

John Connolly: ‘‘This man is so good it’s

terrifying’ and never has this been

more true than in The

Whisperers.

During the war in Iraq

a lead box goes missing from the archives deep in the basement of the Iraq

museum. It is a box that should never be opened, for locked inside are

the

whisperers who with the evil they generate affect all those who come in

contact

with it, let alone open it. A few years later in the US

state of Maine,

Parker is called in by the father of a military veteran of the war to

investigate why his son and other returning soldiers have killed

themselves.

Once involved in this mission Parker finds himself dragged deeper and

deeper

into a situation more terrible than he could ever have imagined. The

novel is a

thriller, but as always with John Connolly it goes far beyond the usual

boundaries of the genre and into the realm of the dark spirits of

another

world. The Collector, who has appeared in previous novels, makes a grim

reappearance and looming over him the terrifying Captain. And Charlie

Parker is

caught between the two worlds.

John

Connolly has

an excellent website http://www.johnconnollybooks.com

on which he

patiently answers a great many of the questions that have been put to

him over

the years. Nevertheless he has kindly agreed to answer a few more

…

Q. The X-factor

that makes your

novels so striking is that the narrative has two levels: the real and

– to use

your own word – the nightmarish. Charlie Parker has to

contend with the dangers

of the first and the evil forces of the second. Did you originally plan

for

this series to have this extra level or has it evolved as you were

writing the

novels?

A. Well,

right from the start there was a certain supernatural element to the

books, but

it has become more pronounced as the sequence has progressed.

I suppose

that there were two genres that I loved: mystery fiction, and the

supernatural,

specifically a certain type of English ghost story epitomised by the

work of

M.R. James. While there is a conservative rump in the mystery

genre that

views one genre as the antithesis of the other, mainly out of a blind

loyalty

to a certain form of rationalism, and a very limited view of the

mystery

genre’s potential for development, they actually have very

similar roots: they

both examine the consequences when the ‘other’

intrudes into everyday life,

that outside force that does not operate by the same set of

suppositions by

which we ourselves operate. In one genre, that force is human

by nature,

and in the other it is not, but the results are the same.

Q. The

Whisperers is brilliantly constructed. Firstly,

the plot is developed

on a jigsaw pattern with several groups of interested parties

independently

converging on the box; secondly, Charlie Parker provides a link between

the two

levels, through your use of his first person viewpoint, so that both

the outer

and the inner man have their role in the plot and draw the disparate

strands

together. Do you work on the structure of scenes and technical use of

different

viewpoints before you begin the novel or does this aspect develop

during the

writing?

A. No,

I’m

not much of a planner. Essentially, each novel begins with an

idea, and

maybe one or two scenes. For The Whisperers,

the first

scene that I wrote involved a woman waking up in the night, finding her

partner

missing from their bed, and then watching him as he spoke to something

on the

other side of a locked cellar door. Originally, that was

going to be the

opening for the book, but eventually it ended up about a third of the

way into

it. I tend to be pretty willing to let the novel find its own

way, but

there is always an internal logic at work, and that’s usually

dictated by

Parker’s actions. In the main, though, I view the

first draft simply as a

way of reassuring myself that there’s a book in there

somewhere. My books

tend to be rewritten rather than written, if you know what I

mean. I go

over them again and again, working out the kinks, honing

them. I’m a

compulsive rewriter, and the technical issues that you mention tend to

be dealt

with while I edit.

Q. As

well as thrillers, you have also published other books, including a

collection

of ghost stories. Did your interest in the supernatural world arise

from a love

of classic ghost writers or is it something that evolved in your

imagination,

such as for instance in ‘The Erlking’ where you

take a folk story and build so

impressively on to it?

A. Well,

like I said, I was a big fan of classic ghost stories from a very young

age,

but they didn’t exist in isolation for me. I could

connect them with

other forms of writing in which I was interested, but also with my own

imagination. That’s what writers do: they take pre-existing

forms, and add a

little of themselves to create something new. At least,

that’s what they

should be doing. Oddly enough, I’m pretty sceptical

when it comes to the

supernatural. On the other hand, I still believe in

God. I’ve come

to realise that I’m pretty happy existing in the grey areas.

Q. A major

and deeply moving theme of The Whisperers is

the Iraq war and

more particularly its effects on veterans, both military and civilian.

Have you

visited Iraq or have

you known veterans of military conflicts through your journalistic

career?

A. That was

something that resulted from all of the time I’d spent in the

US in recent

years. I became very interested in the effect of war upon

soldiers, and

followed the gradually increasing coverage of rising suicides, the

jailing of

veterans, and the manner in which so many veterans who were physically

and/or

psychologically damaged were not being treated with the respect and

care they

deserved. In that sense, the book isn’t really

about the Iraq war:

it’s

about the mythologizing of war, and the dehumanizing effect that it has

on

those who serve. I came across a really interesting passage

in Peter

Beaumont’s book The Secret Life of War

that encapsulated a lot of what I

felt, and had learned. In it, he described the changes to the brain

that occur

when it is exposed to particular stresses: in this case, combat

stress.

The brain begins to rewire itself, with the result that, when soldiers

return

home, they are no longer able to function as regular human

beings.

Depending upon a whole lot of factors, these changes may be short-term

or

long-term, but either way the consequences are horrific for families,

for

society, and for the soldiers themselves.

As for

research, I have a friend in the US, Tom

Hyland. He’s thanked at the back of the

book. Tom served in Vietnam, and he

became my touchstone for the experience of what we now call

post-traumatic

stress disorder. The other stuff – details of the

layout of the Iraq Museum, details

of military conduct and practice – can be gleaned from books

and articles,

albeit a great many of them, but at some point you need the human

touch.

At some point, you have to talk to those who have intimate knowledge of

the

subjects about which you’re trying to write. For

that, I think I fall

back on my training in journalism.

Q. For a

long while ghost stories were commercially unpopular. Why do you think

that

they are now cautiously resurrecting themselves in such interestingly

different

guises as yours?

A. I think

horror fell out of favour, particularly in the UK, because

so much of what was being written was kind of nasty stuff.

That’s a

purely personal view, admittedly, and I might be considered something

of an old

fogey when it comes to supernatural writing, as I prefer the older

nineteenth

and early twentieth century writers, and regard M.R. James as a

suitable full

stop. But that fascination with the supernatural has always

been there,

particularly among younger readers. I mean, that was when I

first became

curious about it, in part because I found it thrilling, but also

because, as a

child, you’re interested in fear, in what frightens you and

its potential

limits. Supernatural fiction becomes a way of making abstract

fears

concrete, and thereby exploring the concept of fear itself.

Now, though,

it seems like vampires have returned to

favour. They’re a bit like chicken, really:

they’re a good carrier for

other things. In the case of, say, the Twilight books, they

become a

means of exploring sexuality and, indeed, sexual abstinence, to which

they’ve

always been ideally suited. It’s just another

variation on what I was

suggesting: supernatural fiction, because it deals with what frightens

us, and

why, has the ability to take on all kinds of interesting issues and

concerns

because it is, basically, metaphorical by nature.

Q. In your

short story ‘The Inkpot Monkey’ there’s a

lighter side to your writing,

which naturally doesn’t emerge in The

Whisperers, save in

Charlie Parker’s style of thought. Is this an aspect of your

writing you’d like

to give more rein to, perhaps in continuing to write for younger

readers, as in

The Gates.

A. I think

that a streak of dark humour runs through all of my books, but

you’re right: in

the Parker books it’s essentially Parker and, to an extent,

Angel and Louis who

provide a kind of deadpan commentary on occasion. There was a

little of

that in The

Book of Lost Things as well, although only in the

chapters involving

the seven dwarfs, and I wanted to explore that side of my writing a

little

more, which is why I wrote The Gates.

That book allowed my

imagination to run riot, but it met a degree of resistance from some

children’s

buyers, who I think have become suspicious of adult writers moving into

the

realm of children’s fiction. I didn’t see

any conflict, though: my books

have always been fascinated by childhood, so it just seemed like a

natural

progression to me to write a book that my stepchildren could

read.

As for

‘The Inkpot Monkey’, that is blackly funny, but

it was also a way of exploring the nature of the writing process, and

the deal

that writers strike with their imagination and their subconscious in

order to

produce their work. I’m very fond of that little

story!

Q. Did you

always hanker to write thrillers, or did you set out by wanting to

write ghost

stories?

A. No, I

think my attraction was always to the figure of the detective, and the

idea of

exploration, of digging, of uncovering old secrets.

Gradually, though, those

secrets began to take on an arcane tinge. Now, I just call

what I do

mysteries, but I probably do so with an awareness of the older meaning

of that

term.

Q. The

forces of evil in The Whisperers, represented

by Herod, the

Collector and the Captain, are memorable to say the least. Did they

spring

ready-formed into your imagination as characters, or did you create

them little

by little? One of the most interesting aspects of Herod, for example,

is that

he (like Hitler) has good points (relatively!) which have the effect of

making

the character all the more chillingly believable.

A. The

villains really are strange products of my subconscious.

It’s often not

until I actually reach the point in the book where they make their

first

appearance that they assume a concrete form. Prior

to that, they

tend to nebulous. In each case, though, they bring with them

human

characteristics. They may be monstrous, or grotesque, but

they are that

way because of their warped humanity. Herod is a being in

torment.

He is suffering in unimaginable ways, and he has been promised both an

end to

that suffering, and a means of visiting it on others.

It’s the latter

that makes him evil: again and again, my books come back to the

question of

empathy, and the belief that its absence constitutes evil.

Herod is evil

because he believes others should suffer as he suffers. His

is a cancer

of the soul.

Q. Do you

ever scare yourself while you’re writing, or do you manage to

remain on the

edge of the action in your mind? Do you always know where a situation

is going

to lead you?

A. No, I

don’t frighten myself. I’m sometimes a

little surprised by what I’ve

written when I go back over it, but I think most writers have a couple

of

moments like that in every book, that sense of ‘Where did

that come

from?’ I’m rarely fully aware of how a

chapter, or an idea, is going to

develop, but I don’t want that to sound like I think

I’m channelling God or

anything. By now, I’ve learned that the book is in

my head somewhere, and

the hard work is sitting down at my desk and typing so that those vague

ideas

can assume a concrete form.

Q. Charlie

Parker is a fascinating character, partly because, to me at least, he

is

somewhat of an enigma. Professional sleuth is one side of his role as

the

novel’s protagonist, but he is also the link to the darker

supernatural forces

unleashed in ever increasing fury, which he faces not only on behalf of

the

main plot but through the tragedy of his wife and daughter’s

murders. Quite a

lot for one man’s shoulders, but he comes across to the

reader very vividly –

perhaps because, as you said yourself of this novel, ‘there

is no single

character in the book who is entirely certain of what is happening, and

that

includes Parker himself.’ Do you know yourself where the

novel is going, or are

you sharing the journey with him?

A. My

experience of writing a novel is, at times, a little like the

reader’s

experience of first reading it. It develops in strange and

sometimes

unexpected directions. But when it comes to Parker, there is

so much of

him in me, and me in him, that when I start writing the books I fit

quite

naturally into his thought processes, and I readily inhabit his

consciousness. I was once accused of something called

‘pinball plotting’,

a phrase I kind of understand but don’t necessarily agree

applies to what I

do. Parker, it seems to me, always approaches a problem the

same

way. He even functions a bit like a journalist. He

is told

something. He examines it for gaps in the truth, and finds

the potential

weaknesses. He then goes looking for explanations for those

weaknesses,

and he does so by confronting individuals. He is always

questioning, and

he is prepared to accept that any answers he gets will always be

partial.

But his quest in each book is part of a larger search, one that is

ultimately

tied up with his own hopes for peace and redemption.

Q. After

your first novel Every Dead Thing all

your novels have been Sunday

Times bestsellers. Do you find the consequent pressure to

produce the next

affects your writing or plotting, or can you cocoon yourself away from

it

during the creative stages?

A. I made a

decision very early on in my career that each book would be a reaction

to the

last, and I would try not to repeat myself, or fall into a set

pattern.

That has meant writing non-mysteries, or a book of short stories, or a

children’s book, or writing a book like The Reapers,

which throws away

all of the supernatural elements and the first person narration while

still

fitting recognizably into the Parker series. Often,

the experiments

are done out of contract, although so far my publishers have not turned

any of

them down.

The downside

of working in this way is that,

ultimately, I know my sales have probably suffered a little, because

just as a

certain type of reader is getting a handle on you, you go and do

something

else, and the secret of success in genre fiction is to write the same

thing

every year with only a slight twist. Readers are

more loyal to

characters than to writers, for the most part. They have a

low tolerance

for experimentation.

Had I done a

Parker book every year for the past dozen

years, I’d probably be in a different position from the one I

occupy – and

don’t get me wrong, my sales are good, and I’m not

complaining about them – but

I’d be miserable, and the books would have suffered as a

consequence. So

now, I think, my publishers and my agent and I have reached an

accommodation of

sorts: I follow my heart, I write what I want to write, and if

it’s not a

Parker novel every year, then so be it. I have enough loyal

readers to

sustain me through these excursions into other areas of writing, and

I’m very

fortunate in having publishers who are immensely supportive of what I

do, and

have never tried to steer me in a particular direction.

I’m lucky, and I

know it.

Q. Your 2006

novel, The

Book of Lost Things, not in the Charlie Parker

series, is about the

power that folklore and fairy stories can have, and Celtic folklore is

particularly evocative. Is Charlie Parker’s involvement with

the forces of evil

in The Whisperers taking this

one stage further?

A. Perhaps

all of the books reflect back on one another, and there are elements

that are

common to them all. After all, each is the product of the

same mind, and

that mind has certain subjects that fascinate it: myths, childhood,

evil, love,

loyalty, redemption. Actually, though, I don’t

think Celtic folklore plays

any part in what I do, at least not directly. My exposure to it as part

of my

culture probably makes me more alive to the possibilities of mythology

in

general, but influences on The Book of Lost Things

are primarily

European.

Q.

You’re a

native Dubliner, and Dublin is home

to a great many writers past and present, but all the Charlie Parker

novels are

set in Maine, where

you spend a lot of your time. What drew you to that state in

particular? And

could you envisage setting a thriller in Dublin or is

that too close to home to work for you?

A. I worked

in Maine for a

time in 1991, and just fell in love with it. It was similar

to Ireland, in

certain ways, while being sufficiently different from home to still

seem like a

strange, slightly foreign place. I like the dramatic changes

of season,

the landscape, the history, and I’ve been able to draw on all

of those things

to create resonances in my work between the physical world and the

internal

world of the novels and their characters.

As for

setting a thriller in Dublin, I think

I’d just write a bad Irish book, because my heart

wouldn’t be in it. I

admire the Irish writers who are producing such excellent crime

fiction, but

they’re much better at it than I would be.

I’ve found a way of writing

that suits me, and I haven’t exhausted its possibilities yet.

You write on

your website that all authors are

constantly looking for the one person in the room who isn’t

clapping because

that’s the person who has figured out what frauds they are.

Well, in your case

it won’t be me! No way. Thank you for agreeing to

answer these questions

– and for writing The Whisperers.

The

Whisperers (Hodder

& Stoughton, hardcover, £17.99, 13

May 2010)

|